In 1885, farmers armed with squirrel rifles and shotguns grimly waited southwest of Sedalia, Mo. Their intention wasn’t to rob the coming cattle drive, but to turn the Texas longhorns back to Kansas or shoot them.

In that year about fifty thousand longhorns had been driven across the Red River for shipment to eastern markets. Missourians had noticed their cattle were dying in fields where the longhorns also grazed. Suspecting the scraggly longhorns were bringing Texas Fever to their state, farmers took action to save their herds. In December, Missouri joined Kansas and Oklahoma in a ban on Texas cattle, effectively ending the great cattle drives.

In what was probably the first scientific partnership between two land grant universities, researchers from the new agriculture colleges in Missouri and Texas pooled their efforts to identify the cause of the Texas Fever epidemic and create a method of controlling it.

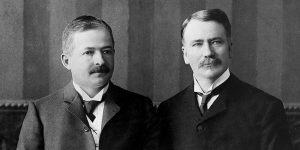

The effort was a true collaboration. A Texas A&M veterinarian, Mark Francis (1862-1936), was a clinician who worked on the practical elements of prevention. He sent his samples and data to Mizzou where John Connaway (1859-1947), a DVM and M.D. trained in the pathobiology of diseases, worked out the science. Today, both universities remember these men with research buildings named in their honor.

A Difficult Disease

Texas Fever was first noticed in Pennsylvania in 1796 after cattle from the South were introduced. That state, and Virginia and North Carolina, restricted importation.

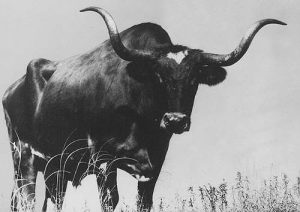

The disease defied easy explanation. It started in affected cattle with a high fever, then emaciation, anemia and, eventually, death. The rangy, tough longhorns seemed healthy and immune. There was also a seasonal and geographic component to the disease – it disappeared each winter north of a “Fever Line” only to reappear with fresh Texas cattle in the spring.

After the Civil War, one of the first tasks given to the new Department of Agriculture was to eradicate Texas Fever that was causing a beef shortage with its sky-high consumer prices. USDA scientists suspected that ticks dropped off the Texas longhorns and found local cattle to feed on, transmitting the deadly disease that the longhorns had grown immune to. After two decades of trying, the federal scientists found little evidence to prove the idea, much less develop a plan to eradicate the problem. Frederick Mumford, the respected Dean of the MU College of Agriculture, suggested that land grant agricultural colleges join the research. His idea was accepted and the project was on.

Francis of Texas, Connaway from Missouri

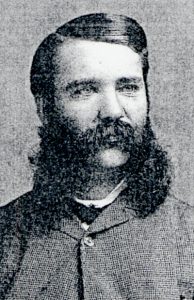

Mark Francis was born March 19, 1863, on a 250-acre farm south of Shandon, Ohio. He was the first person to graduate from the veterinary school at The Ohio State University.

Degreed veterinarians were rare and Francis accepted a faculty position at Texas’s land grant university, Texas A&M, southeast of the railway depot of Bryan. He was shocked at what he saw. The university was housed in a single four-story building called Old Main in the middle of a desolate, hot and dusty prairie.

He barely had time to unpack when he was given the assignment to take 18 longhorns (with special permission) by train to Columbia where research into Texas Fever had already begun on an isolated research farm south of Hallsville. Funded through the Hatch Act of 1887, the Missouri Experiment Station was run by Paul Paquin, a DVM (McGill University) and M.D. (University of Missouri). Dr. Paquin was one of the nation’s most respected authorities on disease, having studied under pioneering microbiologists Edmond Nocard and Louis Pasteur. Dr. Paquin had made a name for himself researching smallpox, rabies, pleuropneumonia, anthrax and others. That such a person as Dr. Paquin was involved was a testament to the economic importance of solving the Texas Fever problem.

After coming from the stark Texas campus, MU’s College of Agriculture seemed luxurious to Francis. Dr. Paquin even had a staff, one of whom had earned a comparative anatomy degree (Chicago Veterinary College) and was completing studies at MU’s Division of Human Medicine. John Connaway, like Dr. Paquin, was a follower of Sir William Osler’s One Health concept. This idea focuses on the commonality of human and veterinary medicine in public health, emerging infectious diseases, food safety and disease prevention. With its colleges of medicine, nursing, veterinary medicine, and animal and plant sciences on one campus, MU continues One Medicine research today as one of its Mizzou Advantage initiatives.

Connaway, born Nov. 18, 1859, on a small farm near Stockton, Mo., became fast friends with Francis – an association that would last 40 years.

Many Skills to One Goal

Dr. Paquin had already traded data with Theobald Smith (M.D. and Ph.D.) and Fred Lucius Kilborne (DVM) of the USDA when Francis arrived. Using discoveries of pioneer bacteriologists Robert Koch of Germany and Pasteur of France, the three had narrowed their search to a disease-causing bacteria. They hoped to develop a vaccination similar to ones that Pasteur devised to prevent chicken cholera and anthrax.

It was a critical clue that Texas Fever manifested itself as a blood-borne disease. Drs. Paquin and Smith and Kilborne suspected that a microscopic protozoan was inhabiting and destroying red blood cells in infected animals. All three agreed that the disease was probably spread by cattle ticks. After sucking blood from an infected but immune animal, a tick would drop off into the grass and lay eggs from which would hatch young ticks already harboring the protozoan. Weeks after the original tick dropped from its longhorn host, its progeny were still capable of infecting other non-immune cattle. The disease died off seasonally when freezing weather in northern climates killed the ticks and their eggs.

Francis not only brought Texas cows to Missouri to study, but the ticks that infested them. Dr. Paquin and Connaway pulled the insects from the Texas cows and applied them to certain Missouri cows while leaving others alone as a control. Cows with the ticks developed Texas Fever. Finally, there was scientific proof.

While Dr. Paquin and Connaway shared the discoveries with their colleagues in Washington, Francis was back on the Missouri-Kansas-Texas (MKT) train to Texas to work on some sort of interim system of prevention.

Trial and Error in Texas

Opinions on Texas Fever among Texas cattlemen ranged from “it doesn’t exist” to “it’s caused by fecal contamination” to “bad water.” Francis was intrigued by a spray station constructed at the famous King Ranch where all sorts of concoctions (including arsenic and cotton seed oil) were sprayed to kill ticks while leaving the cows unharmed. Francis noted evidence that King cows were rarely associated with Texas Fever.

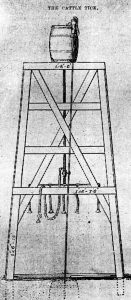

Francis developed his own spraying rig adjacent to a rough-hewn building that would become the first research facility on the A&M campus. He modified the King Ranch formulas until he had one that killed most ticks and rendered the rest infertile. Great news, but the process was too slow for the thousands of cows that made up a typical Texas herd.

In partnership with the King Ranch cowboys, Francis developed a dipping vat that the cows could be quickly run through. Some “dipped” cows were shipped to Columbia to repeat the earlier test where Connaway, now M.D. and DVM, was running the show (Dr. Paquin had been lured to a Battle Creek, Mich., sanitarium by Dr. John Harvey Kellogg who was exploring ways to improve health via nutrition and exercise).

Dr. Connaway transferred the still-living ticks to Missouri cattle and waited. The local cows got sick, but didn’t die. A crude, but practical, prevention system was now available even as the pathology of the disease was being uncovered.

Science in Missouri

Dean Mumford saw promise in Dr. Connaway’s research and arranged for him to get additional education in Germany where the sciences of bacteriology, pathology and immunology were more advanced.

With that, things happened fast. In 1893 using more detailed data from Dr. Connaway, Dr. Smith and Kilborne announced the isolation of the pathogen of Texas fever – the disease was caused by a microscopic protozoan that inhabits and destroys red blood cells. They named it Pyrosoma bigeminum.

Dr. Connaway now turned to developing an immunization protocol. Noting evidence that blood taken from animals who had endured and recovered from a disease could be developed into a serum, Connaway traveled to the Kansas City Stockyards to collect blood from Texas longhorns. He prepared promising test inoculations. Using 100 ticks sent up from Texas by Francis, he infected several dozen Missouri cows and waited for the results.

The infected but not inoculated cattle sickened and died as expected. The inoculated cows developed fevers to 106 degrees F., but showed no other signs of infection. As these results went back to the Department of Agriculture, Dr. Connaway and Francis began to immunize cattle in their respective states.

Problems in Texas

With a robust animal science division at Mizzou’s College of Agriculture and three major private colleges of veterinary medicine in the state, Missouri had a good infrastructure to begin the work. Not so in Texas.

In 1900 there were fewer than a dozen trained Texas veterinarians with the clinical skills to handle the process. Francis personally inoculated thousands of animals, telling each rancher of the critical need for a veterinary medical school to educate professionals to serve the state’s needs.

Traveling the state’s notorious bad roads by buggy, Francis was quickly exhausted. He adopted Dr. Connaway’s idea of creating a central immunization station. Soon, cows were grazing all over the A&M campus. In 1906 Robert Milner, president of Texas A&M, called Francis in with the demand to move his cows somewhere else. They were moved west of campus, coincidentally where the Texas A&M veterinary medicine college now sits.

The Lasting Impact

In 1916, the Texas Legislature funded the School of Veterinary Medicine (now Texas A&M Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences) and named Francis as its first Dean. Mumford named Dr. Connaway the head of the Division of Animal Science of the MU College of Agriculture. Its veterinary medicine department turned into the MU College of Veterinary Medicine in 1945.

Dr. Connaway started his medical education only 30 years after the discovery of germs and their role in infectious diseases. His research with Texas Fever, and later Hog Cholera, has been recognized as paving the way for the control of malaria, yellow fever and other insect-borne diseases.

Francis Hall, completed in 1918, was Texas A&M’s first real veterinary medicine facility. Connaway Hall, also a three-story stone structure and built in 1910, today houses MU bacteriology and parasitology research.

Texas Fever is considered an eradicated disease today.

Dr. Connaway is buried in Columbia, Francis in College Station.

Sources for this story include the Kansas Museum of History, Texas Historical Society, the State Historical Society of Missouri, Texas A&M University, University of Missouri Archives, Texas A&M Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences and MU College of Veterinary Medicine. Material also came from the book Visions of Two Pioneer Veterinarians by George Shelton, retired Associate Dean of the MU College of Veterinary Medicine and retired Dean of the Texas A&M Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences.