A team of College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources’ food scientists at Mizzou are pioneering the use of 4D food printing technology to revolutionize how meals are made for people with dysphagia, a condition that makes swallowing difficult. Their work aims to improve nutrition and safety while making pureed foods more visually appealing and appetizing.

Up to one-third of older adults may experience dysphasia; it is especially common in those who have experienced a stroke or neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson disease.

The project — led by Mengshi Lin, Curators’ Distinguished Professor of Food Science, with team members Bongkosh Vardhanabhuti, associate professor of food science, and doctoral student Changhua Su — focuses on using purple sweet potatoes and pea protein to develop customizable, nutritious meals that change color and shape over time — a key innovation that sets 4D printing apart from its 3D predecessor.

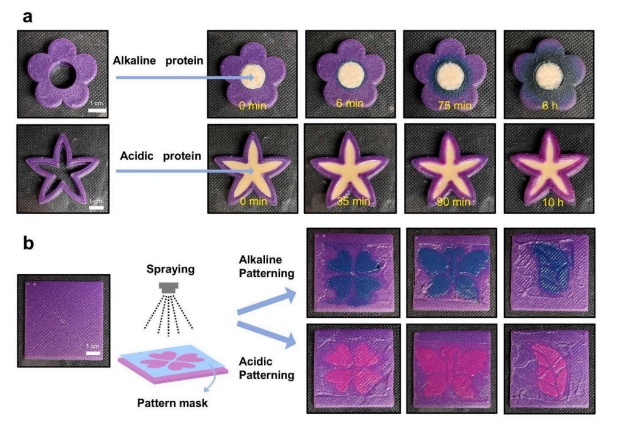

“3D food printing builds food layer by layer through an extrusion-based printer, much like printing with plastic or resin,” Su explained. “But 4D food printing adds the dimension of time — foods can transform in response to stimuli like moisture, pH, heat, or light.”

For example, the team successfully printed edible flowers using purple sweet potato-based ink. Because the potato is rich in anthocyanins, the flowers can gradually change color when exposed to acidic or alkaline environments, such as during digestion or after exposure to different sauces.

The research has wide-ranging implications, particularly for patients with dysphagia, who often rely on bland, uniform purees. Traditional diets for these individuals can be unappetizing and indistinguishable — leading to reduced food intake and poor nutrition. Dysphagia is even associated with increased risk of pneumonia.

“Our goal is to print meals that are soft and safe to swallow, but also visually recognizable and customizable,” Su said. “We found that patients eat more when they’re able to identify the foods on their plates.”

The team’s formulations are carefully tested to ensure they meet International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative (IDDSI) texture requirements.

“The potato-pea protein mixture is soft enough for dysphagia patients but holds its shape overnight,” said Lin.

He explained that this demonstrates that the food can be printed to a variety of appealing shapes and the shape will hold up long enough to be served to patients.

Beyond clinical uses, 3D and 4D food printing may also help reduce food waste. The lab has repurposed imperfect vegetables like misshapen carrots and beets — normally discarded for not meeting cosmetic standards — by processing them into printable powders. These powders are combined with binding agents to create nutrient-rich snacks like crackers.

Currently, the team operates two main food printers that can be used for multi-material printing and includes built-in heating to simulate cooking during the printing process.

Though still in its early stages, the research has already yielded published studies. The lab’s previous PhD student, Ezgi Pulatsu, contributed significantly to the field and now works as a scientist at the University of Ottawa. Su joined the project in 2022 and continues to build on that foundation. Additionally, Dr. Jian Lin, an associate professor in the Department of Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering, also served as Co-PI on a completed USDA project, contributing to this study.

The team hopes to secure additional funding to further the research and eventually bring the technology to market.

“Our vision is to commercialize this — perhaps launch a startup or partner with hospitals to serve patient-friendly meals,” said Lin. “But more research is needed before we can scale up.”

While still rare in real-world applications, food printing has been used to create plant-based steaks and 3D-printed pizzas in Europe and the U.S., though only in limited cases.

What makes this study stand out, the researchers said, is its specific focus on a vulnerable population.

“This isn’t just about futuristic food,” Su added. “It’s about making life better — and mealtime more joyful — for people who often don’t get that experience.”

For now, the team continues refining their techniques and ingredients, hopeful that one day, printed meals will be as common as microwaved ones — only healthier, more sustainable, and far more colorful.