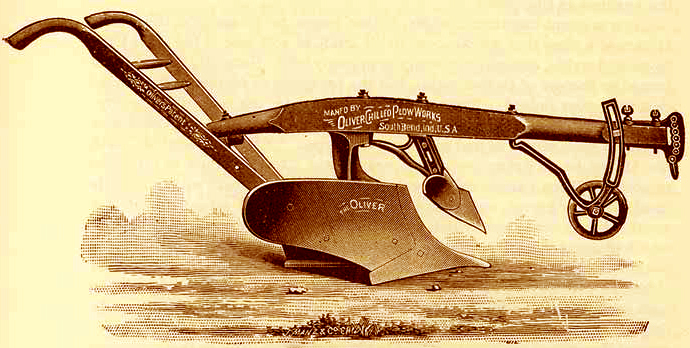

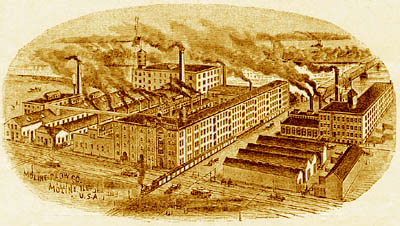

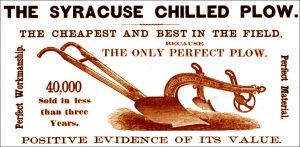

The post-Civil War years saw tremendous change in agricultural technology. Factories that mass produced cannons and rifles turned to making new designs of plows and threshers. Railroad expansion made shipment of these devices cheap and reliable. The new printed catalog meant farmers didn’t have to buy what the local blacksmith produced. Hundreds of new choices were now within practical reach of even the most rural farmer.

But there was a problem. Another new invention of the day, advertising, breathlessly made every new apparatus seem perfect and able to do everything. It would be another seven decades before Consumer Reports magazine tested products and provided objective data to consumers.

In 1872 the Missouri College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts was not yet 2 years old and yearning to provide a service to farmers. With no buildings, a contentious beginning, few professors and students, and an uncertain curriculum, that was a daunting challenge. The Dean of MU Agriculture, the geologist turned agriculturalist George Swallow, dreamed up a plan.

The new College would conduct a national contest to determine the best of the new plows for various soil, crops and climate conditions. Their effectiveness would be judged by measureable methods by experts in agriculture and science. For a new College with no reputation, the response was surprising. Fifty entries from six states were received. Most of the best manufacturing establishments in the country participated. Farmers and ag magazine writers from around the Midwest signed up to watch. The trial was front page news as far away as Chicago.

A High-Tech Question in 1872

Swallow’s timing was perfect. The need to scientifically evaluate new farm designs had become a hot topic when plows that worked well east of the Mississippi River failed to bust the hard sod of Kansas. Missouri, with its multitude of soil types, was a natural testing ground for new plows.

The choice of a plow was a big deal to farmers — it was their greatest single technological expenditure. Pioneers braving the hardships of Kansas and Nebraska couldn’t make a mistake on their choice.

The Missouri Plow Trial was conducted May 16-20, 1872, mostly on the MU Agricultural Farm on land now occupied by Mizzou’s Memorial Union, Gentry Hall, Read Hall and Agriculture Building. The College’s faculty and students provided the labor, as well as lending the mules and horses.

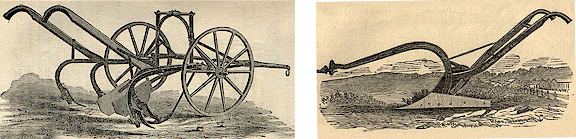

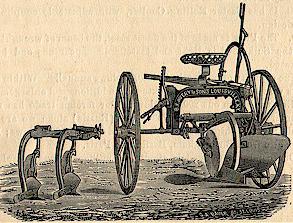

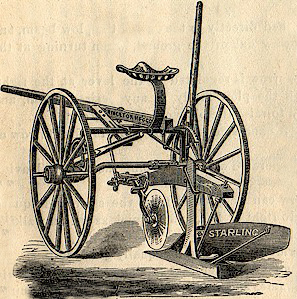

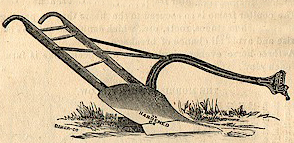

Plows were entered in the following classes: Sulky Plows, Sulky Attachments, Walking Plows, Gang Plows, Reversible Plows, Subsoil Plows, Prairie Breakers and Sod Plows. “Sulky” plows were the latest post-Civil War refinement — operators sat on the device rather than walking behind it.

Judges were G.C. Swallow, dean of agricultural college; J.P. McAffee, master of the Boone Grange; W.L. Victor, W.T. Hickman and S.B. Spence from the Boone Grange; and J.G. Potts, J.L. Sterne and J.C. Gillaspy from the Boone County Agricultural and Mechanical Association.

Dean Swallow and his faculty came up with a scientific grading system: Quality of work: 25 percent of score, adjustability: 20 percent, durability: 20 percent, simplicity: 15 percent and draft: 20 percent.

Part Science, Part Sporting Event

The judges, often dressed in long dress coats and bowler hats that were popular among the educated classes, weighed each implement, timed how long it took to harness it to a horse, measured its turning radius and the depth of its furrows, how long it took to sharpen and dozens of other tests that farmers would recognize and appreciate. The scientific “Dynamometer tests” were judged on “draft per square inch of furrow section, area of section of furrow, draft in pounds, depth and width of furrows and width of plow.”

Visiting farmers, reporters and representatives of the manufacturers watched each test. Field test results were posted immediately, giving the proceedings the feel of a sporting event.

The results of the 1872 Missouri Plow Trial were:

- Sulky Plows in Bluegrass Sod: Winner: the Starling, made by the Princeton Manufacturing Co., Princeton, Ill.

- Prairie Breakers in Bluegrass Sod: Winner: the Evans, Moline Plow Co., Kansas City.

- Walking Plows in Bluegrass Sod: Winner: the Speer Walking Plow, A. Speer and Son Company, Pittsburgh.

- Sulky Plows in Old Bottom Soil: Winner: the Hughes, Hughes Plow Co., St. Louis.

- Sulky Attachments in Old Bottom Soil: Winner: the Slusser, L. Yinger Company, St. Louis.

- Walking Plows in Old Bottom Soil: Winner: the Moline Walking Plow, Moline Plow Co., manufactured in Kansas City.

- Reversible Plows in Old Bottom Soil: Winner: the Hillside Plow, Laur and Hartman Company, Louisville, Ky.

- Gang Plows in Old Bottom Soil: Winner: the Gang Plow, B.F. Avery and Sons, Louisville, Ky.

One of Missouri’s most popular plows, the Morrison Steel Beam Walking Plow, performed poorly in the tests. Judges noted its few strengths and several deficiencies, to the annoyance of company representatives sent to Columbia. Reporters wrote that they were impressed — Missouri’s new College of Agriculture was a place of integrity that didn’t bow to local political and economic pressures.

Final results of the tests were published in Midwestern newspapers and national ag magazines. MU plow tests continued as an annual event until 1888.