More than 2 billion people suffer from hidden hunger, a form of malnutrition where individuals lack essential micronutrients — like vitamins and minerals — even though they consume what appears to be an adequate amount of calories.

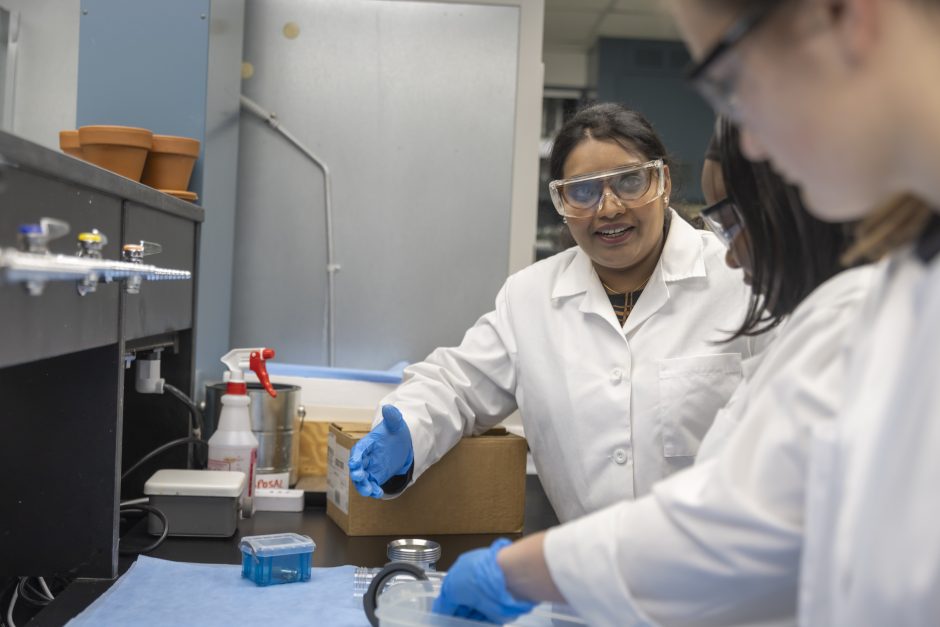

University of Missouri researcher Kiruba Krishnaswamy is focused on tackling this global challenge. She recently received a five-year, $532,000 Early Career Development (CAREER) award from the National Science Foundation (NSF) — the NSF’s most prestigious award for early-career faculty — in support of her project titled “FEAST (food ecosystems and circularity for sustainable transformation) framework to address hidden hunger.”

“Food is a universal basic human right,” said Krishnaswamy, an assistant professor with joint appointments in the MU College of Engineering and MU College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources. “Whenever we talk about hunger, we usually talk about chronic hunger, but hidden hunger is much more dangerous. If we don’t have enough micronutrients, our bodies won’t be able to absorb the required nutrients. This can create a snowball effect — leading to serious health issues like spina bifida, iron deficiency and anemia.”

Recognizing the urgent need for groundbreaking solutions, Krishnaswamy launched a project that incorporates engineering innovations in the creation of a culturally appropriate, circular food system model — a sustainable alternative to the existing linear food system.

“A linear food system is more focused on quantity or production, and sometimes during that process, food quality standards are not met,” Krishnaswamy said. “This can lead to people consuming empty calories. But, by making the system more circular, we’re tailoring solutions to the specific needs of individual communities, and then everyone can get the benefit of nutritious food in larger quantities.”

By addressing the specific needs of different under-resourced communities, Krishnaswamy aims to address the root cause of hidden hunger — and through that effort fight the related problem of chronic hunger.

Building a sustainable model

As part of the project, Krishnaswamy is partnering with the Osage Nation in Pawhuska, Oklahoma, to address hidden hunger and support food sovereignty — community-based, self-sustainable food practices — within the community. This process emphasizes the importance of preserving traditional agriculture practices while being ecologically sustainable.

Krishnaswamy has three main research goals for this part of the project. They are:

- Understanding interactions: Investigating specific interactions in the soil-water-plant-food-people chain to pinpoint micronutrient deficiencies and inform targeted interventions.

- Sustainable food processing: Exploring sustainable food process engineering strategies to enhance the nutrition, accessibility and availability of traditional Osage foods, such as elderberry.

- FEAST framework development: Co-creating a FEAST framework integrating circular food systems and sustainable development goals to bolster food and nutrition security in the Osage Nation and beyond.

“Undernourishment and obesity are what we call the double burden of malnutrition because people are eating food, but they aren’t getting the right amount of nutrition,” Krishnaswamy said. “Recent studies have found micronutrients are a common connector between these two problems.”

It’s important to Krishnaswamy, whose grandfather was a farmer in India, to ensure that whatever process she designs respects and fits the culture it’s intended for.

“We could develop something in the lab, but if it’s not culturally appropriate or socially acceptable, then it’s not going to reach people,” Krishnaswamy said. “As a researcher, I learn a lot from the community members I meet, and it’s eye-opening to hear their stories. By listening to what they need, we can develop solutions based on what their specific needs and wants are.”

The project is committed to fostering educational outreach and community engagement by seeking to increase awareness about hidden hunger, sustainable food processing and sustainable development goals.

“I am grateful for this opportunity,” Krishnaswamy said. “Mizzou is a comprehensive place with researchers from all disciplines — from agriculture to engineering and medicine — where you can reach out to someone for help, and they get back to you or direct you to someone else who can assist.”

Krishnaswamy said she’s humbled to receive the NSF award and credits her support system, her family, students, colleagues and mentors — including the MU CAREER Club and community partners at the Osage Nation — for inspiring her to tackle difficult topics and help drive her goals for the field forward.