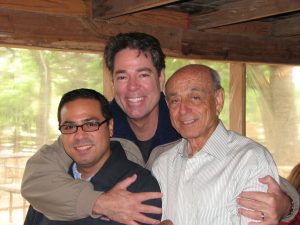

Humberto Castro BS Ag ’50, MS ’59 is not one to normally boast about himself. Even with all of his both business-related and personal successes and accomplishments achieved in the more than nine decades of his life, Humberto prefers to not have the limelight pointed at him. Instead, the man who is still very active at 98 years old, normally lets his actions do the talking.

“So we’ll do it for him,” says his oldest son, Leslie Castro.

Talk to his family members and they will tell you of a Peru native who first came to the United States in 1945 to attend the University of Missouri as one of its first Latin American students.

“For one thing, he’s never met a person he doesn’t make a friend of. He meets people very easily. He’s very open and very friendly,” Leslie adds. “He’s almost like Inspector Clouseau in ‘The Pink Panther.’ It doesn’t matter what happens, he lands on his feet and everybody scratches their heads.”

They will talk about how he was able to take the training and research skills obtained from his master’s thesis on hybrid sorghum research at the College of Agriculture at Mizzou 10 years after his initial journey to Columbia, to make a profound impact on the livelihood and food production of farmers throughout Mexico and south Texas — who then went on to run several entrepreneurial, retail and real estate ventures in south Texas.

“He was just always into something new,” adds his daughter, Jo Anna “Jo” Ordonez. “He could never really sit still, and was very successful.”

Most importantly, they tell you of a charitable person who always shares his time and resources, while approaching life with a grace and buoyancy that allows him to still find time to glide across the dance floor.

“He has always seemed much younger than himself,” says Leslie of his father, who grew up watching the tango and the waltz. “At 98, people think he’s in his 80s.”

“A lot of people, they see the business man, who is very intelligent, very smart, but I see the spiritual man who cares about people a lot,” adds his dance partner of 48 years, his wife, Sylvia, who works as a realtor.

In the spirit of his generosity, an endowed annual scholarship has recently been set up in his name for students enrolled in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources, preferably for those of, like Humberto, Hispanic or Latino heritage.

Humberto lives in Brownsville, Texas — a geographic representation of the bilingual life he has led since finishing his master’s degree at Mizzou. Although he has not returned to Columbia since graduating, the university has always had a soft place in his heart.

“They gave me knowledge to develop my desire, my love,” he says, “to do something for other people.”

A change of scenery

Humberto grew up as the middle child of three in Peru’s capital city of Lima, having been born in 1922. His father, Emilio Castro Cortez, was a lieutenant in the Peruvian Army, before switching to serving as the police chief of mining town Casapalca and later a businessman managing cotton gins and farms. Following the impacts of the Great Depression, Humberto’s father would eventually become part of a team that would form Peru’s first social security program.

Out of all of the influences in his childhood, Humberto found the most inspiration from his grandmother on his mother’s side, Elena Guillen, who ran, among other ventures, a noodle factory and a bakery to help supply the Peruvian Navy and Army with food supplies when World War I began.

“She was a businesswoman when there were no businesswomen in Lima,” Humberto says. “She was very smart, very brilliant. She ran her own businesses, and she was very respected. She was an inspiration with her love, her intelligence and her ways of being.

“She always encouraged me and my siblings to be better and to improve ourselves.”

It was at the noodle factory where a young Emilio, as a member of the Army, would first lock eyes on Humberto’s mother, Zoila Rosa while picking up an order.

“He got a look at my mom and then they fell in love,” Humberto says.

In high school, Humberto would compete in amateur national championships as a track and field star in the 200- and 400-meter races. It was also in high school where he would first hear about the University of Missouri through the school’s principal, who had earned a degree from a teachers college in Missouri. The principal would first tell him about all of the research developments that were taking place at Mizzou and at other U.S. universities.

Following one year at the University of Trujillo in Peru, Humberto decided to see Mizzou for himself. He wrote to the university’s admissions office. He received a letter back that said if he could pass the admissions test, he would be accepted.

“I wanted to get to know the people, to get to know the country and to be completely out of any Latin influence,” Humberto said of wanting to study in the United States. “That was in the back of my mind because my main goal was to experience another culture.”

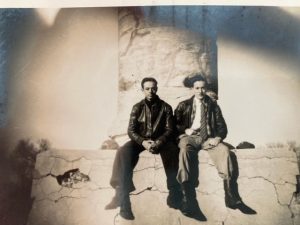

He also convinced one of his best friends, Eugenio Cogorno BS Ag ’49, to join the journey with him.

Given it was the tail end of World War II in the spring of 1945, transportation was highly restrictive, as most transit resources were being used for the war. Realizing the situation, Humberto and Eugenio embraced the circuitous journey that would take them from Peru to Ecuador to Colombia to Panama to Guatemala to Mexico and eventually to Mizzou. Along the way, their modes of transit would include a banana boat, a plane — after they received last-minute tickets via a couple who refused to fly to Guatemala on account of it being Friday the 13th — and a bus.

They would spend several days, if not weeks, at each stop. In the case of Mexico, they lived several months in Mexico City. They would observe the local farming communities, and realize that if there were major research agricultural breakthroughs taking place in the U.S., it could provide an immediate need to the people they encountered along the way.

“It confirmed the need of the people,” Humberto says, “and what the people were looking for.”

Always a pioneer

Eventually, the traveling duo made it to Columbia, their final circuit being a bus ride from St. Louis. Upon their arrival, they took (and passed) the admissions test and would later register for the draft. At the end of his undergraduate studies, Humberto’s number would be called for the Korean War, but with four months until his graduation day, he was able to arrange a deal in which he would enroll after finishing his degree. That time never came, though, as the war ended beforehand.

Being possibly the only Peruvian students on campus at the time, Humberto and Eugenio never lacked for dinner invitations.

“They were very well received,” says Jo Ordonez, who has worked in the industrial water treatment industry for 30 years in central Texas. “They were the anomaly. Everyone wanted to have them over for dinner, so a lot of professors and deans would ask them.”

Upon completing his bachelor’s degree, Humberto returned to Peru to work on a large sugar cane plantation owned by W.R. Grace and Company. He worked there for five years, until the idea of coming back to the University of Missouri for a master’s degree became too strong to not act.

While at his first job, Humberto would have many talks on a weekly basis about new developments in food science with American frozen food pioneer Clarence Birdseye, the namesake of the popular Birdseye frozen foods and meals. Birdseye had come to Peru in the early ’50s in a consultant role to help create a process to convert crushed sugar cane into paper pulp.

When he came back to Mizzou for his master’s degree, he would meet with Emmett Pinnell BS Ag ’40 to determine the topic of his master’s thesis. Pinnell, who served as the chairman of the field crops department at the time, suggested that he look into the surge of research that was taking place around the commercial-scale production of a particular line of grain sorghum, from which a hybrid could be developed.

Unlike the original plant, this new hybrid could adapt to new climates due to its newfound self-pollinating abilities, which were linked to having its male fertility restored by nuclear-encoded restorer genes. These hybrid plants were also found to be more resistant to diseases and insects.

“Exponential agriculture meant he could feed the world and he wanted to be a part of feeding the world,” Leslie says of his father’s passion of researching sorghum, which has several food uses such as cereal grains.

The epicenter of the research could be found at the experiment stations at Texas A&M University, but universities across the country were conducting new experiments with the hybrid.

While completing his master’s degree, Humberto accepted a job at what is now known as the DeKalb Genetics Corporation. He was originally scheduled to move to Italy to begin seed research at a lab there. As fate would have it, though, he was first stationed at a research facility in Lubbock, Texas, and was asked one day to visit testing plots in Tampico, Mexico. At the time, many Mexican farmers had large fields of cotton, which were being devastated by a surge in boll weevils.

Upon his initial visit to Tampico, Humberto had an epiphany that the new grain sorghum could thrive in the climates of Mexico. He would go on to ask the leadership team at DeKalb if he could do a full report, and possibly introduce the hybrid sorghum grains to Mexico. They agreed, and he began introducing the seeds to farmers in Mexico in January 1960. He chose his home base to Brownsville, a Texas town in which one could reach the Mexican border daily crossing the Brownsville & Matamoros International Bridge.

In the first year, he was able to convert approximately 30,000 farmers to change from cotton to the new sorghum hybrid in close to 250,000 acres of land. The numbers only grew from there. Given the instant popularity — and proven results — of the crop change, Humberto was asked to guide the Mexican agriculture department on certification methods for the hybrid sorghum seed in 1962.

DeKalb, and several other competing seed companies, would invest more money into developing several additional lines of grain sorghum. Humberto would receive a commendation from the Agronomy Society of Mexico for his efforts.

Eventually, Humberto would start his own seed company for sorghum and corn hybrids in 1973 by the name of Sedelgo, which sprung from the Spanish term semillas del golfo, or “seeds of the gulf.”

Looking back at his career, he finds the most pride in his introduction of sorghum to Mexico.

“I started something that generated something not only good for the farmers, but good for all of the companies that went in,” Humberto says. “That to me was very valuable… that I introduced something that was useful to produce food.”

A Renaissance man

Even with all of his business dealings, Humberto has always found time to pursue other passions tied to the arts — and make more connections with other people in the communities in which he lived and served. Those include painting, sculpting and directing community theater productions. Humberto and Sylvia have supported artists societies both in Brownsville and in its sister city across the border, Matamoros.

They have also been active members in their church, having been part of numerous charity initiatives. At one point, Humberto had the idea of having a group of children from an orphanage in Mexico come up to Brownsville and the nearby cities and perform various forms of Mexican music and dancing, such as mariachi, folklorico and traditional choir singing. All of the donations generated from these performances would go right back to the orphanage called Ciudad de los Niños in Salamanca, Guanajuato, Mexico.

“My parents led us to a life of service,” Jo Anna recalls.

Leslie — who travels with his German Shepherd, Pepper, across the country to visit incarcerated youth at juvenile detention facilities with his Faithful Friend ministry based out of the Dallas area — remembers one his father’s favorite sayings: “God is always with you. He will always provide.”

But that providence has always run alongside hard work, stemming back to the doctrine that his grandmother instilled in him during his childhood in Lima.

“The impetus from Dad was always ‘improve your mind.’ Even now, he reads avidly,” says Leslie, of the many academic journals or books his father will peruse over the course of a week.

Humberto takes great pride in his children’s academic achievements — and the fact that all three of them have earned both bachelor’s and have earned, or are in the process of earning, their master’s degrees.

What advice does Humberto have for the next CAFNR student who could make a significant contribution to the world’s food supply?

“Never give up. If you fail, try and try again, until it becomes possible, because with God everything is possible.” he says. “Build up your knowledge, become a questioner and always ask questions to improve and increase your knowledge.”

His formula of active and inquisitive has proven to be an effective one, as neither he nor Sylvia show any major signs of wanting to slow down anytime soon.

“My family and I drove in to go see them. We sat in the driveway until 2 a.m. because they were out partying with their friends, and that was two years ago,” Jo Anna says with a laugh.

“He said he’s going to live to 120, so I wouldn’t put it past him.”

Replies Humberto: “That’s what everybody hopes, but I will go when God says, ‘This is the time.’”

Until then, there will always be an article to read, a song to dance to or a garden to tend.