When Ruth Williamson came to Mizzou from Raytown, Missouri, she knew she wanted to at least try undergraduate research. She was passionate about environmental sciences, but wanted to get a deeper understanding of one of the most important parts of our environment: plants.

Soon after her freshman year began, Williamson was accepted to the Pre-MARC program (Maximizing Access to Research Careers), an organization for first- and second-year students to integrate academic and social support with mentoring and paid research opportunities that prepare students to matriculate into research-focused graduate programs. Her curiosity about undergraduate research soon turned into a passion for research and she became a full MARC member during her final year of undergraduate work. Involvement in this organization, and support from the plant sciences and environmental sciences faculty allowed Williamson to pursue innovative research that explores the mechanism that causes being outside to make people feel better.

“There’s a lot of research showing that there are positive effects to being outside,” Williamson said. “We can measure that. People’s stress levels go down, they have an increased immune system, they have increased anti-cancer cells in some cases, which is amazing. So being outside might be a good preventative medicine, but we don’t know how that works. What specifically is making that change in people happen?”

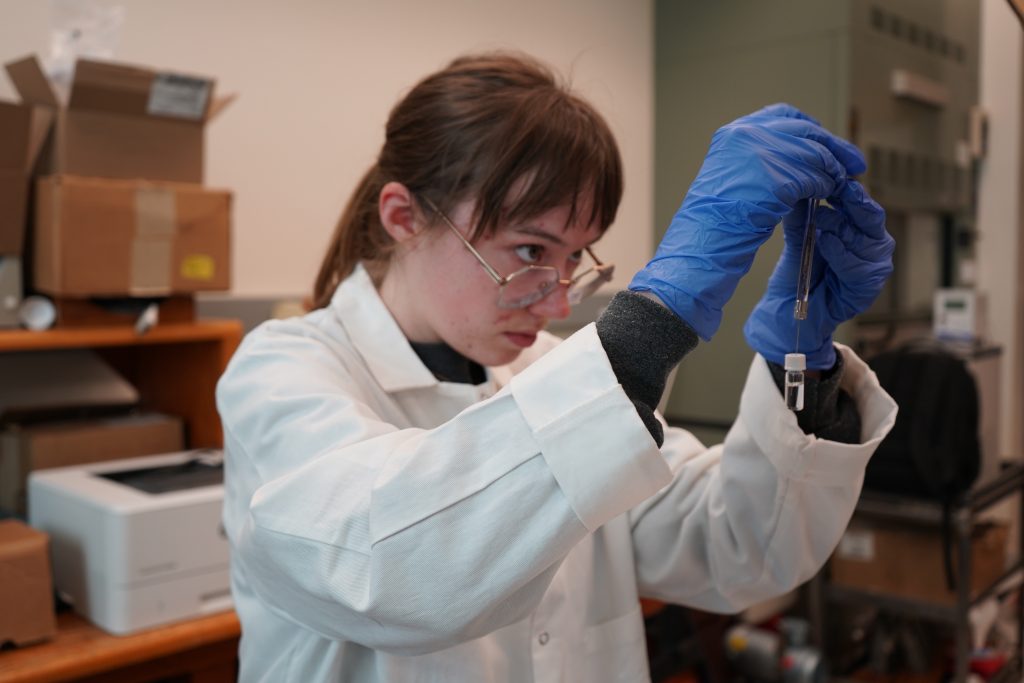

With this question in mind, she embarked on her research project with the Center for Agroforestry to investigate how plants contribute to the positive human health effects of being outside. To do this, she measured a group of molecules called phytoncides, which are like immune system cells released into the air by plants. Humans then breathe in those plant byproducts to positive effects.

“We’re trying to see what phytoncides are present in Missouri,” Williamson said. “There’s been a little bit of research like this done in Asia, but never in the United States.”

Williamson studied a forested location and a non-forested location in the Columbia area at different times of day, collecting samples of outside air as she walked the area, to mimic what a person on a hike or a walk might be exposed to (another research method no one had implemented in this subject matter before). Williamson then took the air samples back to the lab to study what and how many phytoncides they contain from a list of 35 compounds that have been found by other researchers to have positive effects on human health.

“Trying to develop a new method, we’ve had to do some problem solving throughout the project since no one has ever done this before and we weren’t sure what our results would be,” said Williamson. “But all 35 compounds were present in both locations, which was great. Our detection levels are really good, as our machines can detect down to the parts per trillion in the air. We also noticed a difference between the two locations’ levels, and changes in the levels depending on the time of day and time of year. So far, we’ve found that spring seems to have the highest phytoncide levels, which makes sense because the plants are growing and doing a lot of metabolic processes, which means that spring is probably the best time to go on outside walks for the highest amount of health benefits.”

Williamson will be returning to Mizzou in the fall to pursue her PhD and continue her research. She hopes to conduct research in a variety of different locations, in addition to partnering with researchers in the psychology department to further study the positive effects of the plant compounds on humans, in addition to a controlled environment mouse model study to show scientific changes in mice bodies when exposed to the compounds.

She was excited to present to legislators at the Missouri State Capitol on March 13, where she could discuss practical applications of her research on things like city planning and the importance of scientific research to public health.

Williamson wants to encourage students to pursue their research passions during their time at Mizzou, including research outside of your major.

“I’m a plant sciences major, and my lab is in natural resources,” she said. “I think that there needs to be more interdisciplinary crossovers between what you study and what you do research in, because you learn so much more about the way things can click together and the big picture of things. So just look around at labs you might be interested in and don’t be afraid to send an email to professors to get involved; they’re not as scary as you think and it could lead you to a life-changing opportunity.”