Wine is back in Missouri. Vineyards plowed under during Prohibition are blooming again. The state’s wineries are winning international competitions. Viticulture, enology and winemaking are popular courses at the Institute for Continental Climate Viticulture and Enology at the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources at the University of Missouri.

It’s all but forgotten that grape growing and wine making were pivotal parts of MU’s early history. Vineyard donations helped found the College of Agriculture, and students learned the winemaking craft in the basement of the famous, but ill-fated, Academic Hall. Some of the University’s most famous sons got their first taste of wine at MU – both legally and not so legally.

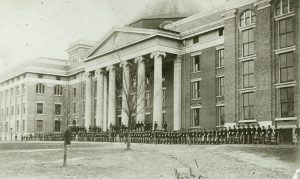

Wine Raids in Academic Hall

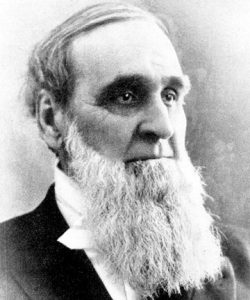

The Missouri College of Agriculture was established in 1870 with help of donations of vineyards. James Rollins, known as the Father of the University, owned a vineyard and orchard just south of Academic Hall that he donated to the College. George Clinton Swallow, first Dean of the College of Agriculture, acquired and donated adjacent grape-growing land.

Swallow is known for his work in geology and surveying, but his expertise was grape growing. The first Dean of the College of Agriculture wasn’t a crop farmer or livestock man, but a viticulturist.

MU’s White Campus, named for the limestone from which the buildings were constructed, was once 40 acres of thriving College of Agriculture grape rows. Memorial Union, the Agriculture Building, Bond Life Sciences Center, Mumford Hall, Lefevre Hall and surrounding buildings were built on what was originally vineyard soil.

Swallow and his students began making wine in basement of Academic Hall for the same reasons CAFNR teaches the subject today and has an experimental winery in Eckles Hall – grape growing and wine making were critical to the state’s economy and needed research support and educated practitioners.

According to a 1908 issue of the University Missourian newspaper, the cellar’s fermentation vat “was as large as a windmill tank.” Its aroma proved too tempting and students began covert “barrel tastings.” An anonymous author wrote a poem describing what became known as “wine raids:”

We come at night

When fleas do bite

And the profs are all a-snoring

We seek the wine

Have heard it’s fine

Get through the floor by boring

Scott Hayes, an 1873 graduate of the College of Agriculture, recounted his youthful follies in an article in the Missouri Alumnus after the turn of the century. Hayes explained that the wine cellar was in the west wing of Academic Hall. Students gained entry through an open window on the floor above. Once in, they cut a hole in the floor above the cellar and ran a hose down to siphon the wine. After they acquired what they came for, the mischievous students left the line in place to taunt the faculty.

Later raids were even better planned. One group of students distracted the building watchman while another group hijacked a five-gallon wine keg.

Such brash acts inspired an early Eugene Field poem.Field attended MU during this period and became a famous children’s writer best known for his poem, Wynken, Blynken and Nod.

Field published his wine poem in the University Missourianin what he termed “rhyme doggerel:”

The Vineyard

By Eugene Field

Into the vineyard I went with Bill

As blithe as youth can be,

As the sun declined beyond the hill

And drowsed in the western sea

And under the arching vines we sat,

And we sampled this and we sampled that

Till we didn’t know where we were at,

Nor the devil a bit cared we.

Out of the vineyard I came with Bill,

Just in time to see

The sun peep over the eastern hill

And grin at Bill and me.

And Bill remarked” “We quit too soon;

Let us sit in the light of that silvery moon

And list to the nightingale’s plaintive tune!”

So back to the vineyard went we.

Years after the raids, a story in the Savitar, MU’s yearbook, tells of five “husky heroes” in the class of 1897 who raided the vat one evening. Their merriment was interrupted “by the report of a shotgun.” The students left “huge remnants of their unmentionables” on nearby barbed wire.

It wasn’t only the wine cellar that was the location of mischief. Several sources mention students having late night soirees in the College vineyards.

Despite distracted students, professors remained determined to provide a quality education. In 1878 Dean Swallow encouraged viticulturist George Husmann to join the faculty at the College of Agriculture.

CAFNR and the Father of Missouri Wine

Husmann, remembered as the Father of the Missouri Wine Industry, was a charter member of the Missouri Horticulture Society and member of the University’s Board of Curators from 1869 to 1872. He published a journal called the Grape Culturist (1869-1873) at a time when no other such periodical existed in the United States.

Husmann and state entomologist Charles V. Riley identified the insect phylloxera as the culprit behind the dying vineyards of France. Husmann, along with Isidor Bush of St. Louis and Hermann Jaeger of Neosho, supplied the French with phylloxera resistant rootstock, thus saving the European vineyards from the soil-borne pest.

However, the French soon learned to propagate their own rootstock. By 1878 Husmann’s nursery business in Sedalia was failing. He readily accepted Dean Swallow’s offer to become the first professor of horticulture and superintendent of pomology and forestry. In 1880 he published his first edition of Grape Growing and Wine Making, an industry standard for many years. Husmann helped establish the Mississippi Valley Horticulture Society which became the American Horticultural Society in 1885. Husmann left Missouri in 1881 and shifted his viticulture efforts to California.

After Prohibition was ratified in 1919, viticulture faded at Mizzou. The once-lush vineyards were plowed under for the expanding campus. The College of Agriculture emphasized other areas of agriculture.

Tiger of the Vineyard

There’s one last chapter in CAFNR’s early wine history.

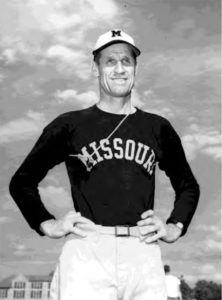

Tiger Football Coach Don Faurot loved wine as much as football, even though he lost two fingers in a sprayer accident while working in his family’s vineyards.

Faurot completed his MU College of Agriculture master’s thesis in 1927 entitled Influence upon production of the different methods of training grapes. He co-authored a research bulletin, A comparison of four systems of pruning grapes, the following year. In 1935 the viticulturist became a coach and led the Tiger Football Team until 1956. Faurot is renowned for the invention of the “T” formation. Faurot Field, stadium of the Fighting Tigers, was named in honor of a man who knew his way around a vineyard as well as a football field.

Today, the University of Missouri has re-established its connection to Missouri’s grape and wine history. The Institute for Continental Climate Viticulture and Enology (ICCVE), underwritten by the Missouri Wine and Grape Board, was established in 2006. With research, teaching and outreach programs, the Institute is building upon a rich heritage with deep roots.