A team of Biochemistry researchers at the University of Missouri has published the first direct evidence that the gene ATP7A is essential for the dietary absorption of the nutrient copper. This research explains why children with Menkes disease, who are born lacking this gene, develop a severe and often fatal copper deficiency.

The research shows that the acquisition of dietary copper is impaired when the ATP7A gene is absent in the intestinal cells of young laboratory mice, resulting in an overall copper deficiency that mimics symptoms of Menkes disease in children. Symptoms include seizures, movement disorder, stunted growth and early mortality.

The results could provide new insight into the human version of the disease. The incidence of Menkes disease in humans is estimated to be 1 in 100,000 newborns. Since newborn screening for this disorder is not routine, and early detection is infrequent because the clinical signs of Menkes disease are subtle in the beginning, the disease may not be treated early enough to make a significant difference.

Children with Menkes disease usually die in the first decade of life. The mice at the University of Missouri in which loss of the ATP7A gene is restricted to specific tissues will provide an important model for discovering new treatments for patients this disorder.

One of the most significant findings was that a single dose of copper injected into mice within a few days of birth restored normal growth and life expectancy. Early intervention was critical, however, because treatment initiated after the onset of symptoms was not successful.

The results were published recently in the American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. Authors are Yanfang Wang, Sha Zhu, Victoria Hodgkinson, Gary Weisman and Michael Petris, researchers in the Department of Biochemistry and the Department of Nutrition and Exercise Physiology at the University of Missouri; and Joseph Prohaska, University of Minnesota Medical School; and Jonathan Gitlin, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Mass. The research was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

The Little-Appreciated Nutrient

Copper is a little-appreciated but essential trace mineral in all body tissues, Petris said. Cells cannot properly use oxygen without copper. Along with iron, it helps in the formation of red blood cells. It also helps keep the blood vessels, nerves, skin, immune system and bones healthy.

Normally, most people get enough of the mineral through food, however, women who are pregnant or breastfeeding may be at risk of copper deficiency due to the high demand for copper during fetal and neonatal development.

Menkes disease occurs when the body is unable to regulate the metabolism of copper taken in by food. Copper begins to accumulate at abnormally low levels in the liver and brain, but at higher than normal levels in the kidney and intestinal lining.

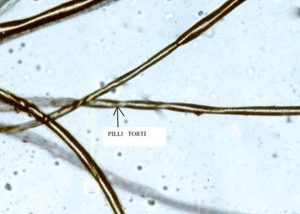

Human infants with this inability to regulate copper may appear healthy at birth and develop normally for 6 to 8 weeks. Then symptoms begin, including floppy muscle tone, seizures and failure to thrive. Menkes disease is also characterized by subnormal body temperature and colorless or steel-colored hair that breaks easily.

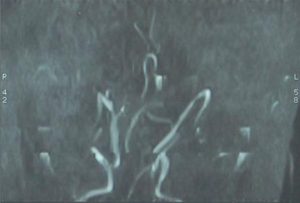

Untreated, Menkes disease often causes extensive neurodegeneration in the gray matter of the brain. Blood vessels in the brain may also be twisted with frayed and split inner walls which can lead to internal bleeding.

Petris, whose lab is characterizing copper pathways and its possible connection to Alzheimer’s disease and cancer, said the research definitively establishes that ATP7A on the X chromosome controls the absorption of copper from food.

Other Copper-Related Diseases?

Researchers have identified more than 100 ATP7A mutations that cause Menkes disease. Many of these mutations delete part of the gene and produce a shortened ATP7A protein that is unable to transport copper. Other mutations insert or modify DNA building blocks, which leads to ATP7A proteins that do not function properly. Mutations in ATP7A have also been shown to cause a type of spinal muscular atrophy that is quite different from the symptoms of Menkes disease.

Petris said that the key to treating Menkes disease depends on ensuring adequate copper enters the brain of affected individuals during the critical neonatal period when copper demand is highest. His lab is also exploring whether different chemical forms of copper are better able to enter the brain and prevent Menkes disease in mice.

Petris said that this work on Menkes disease has far-reaching health implications for the general population because copper underpins many facets of biology. Recent evidence suggests that copper plays a key role in tumor growth because the mineral is essential for blood vessel formation and it regulates pathways of cell division. It may also promote the formation of toxic proteins in Alzheimer’s disease.

The MU Division/Department of Biochemistry is jointly affiliated with the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources and the School of Medicine. The researchers work in MU’s Bond Life Sciences Center.