Computers today are ubiquitous, living not only on every desktop but in most people’s pockets. Only retirees remember the earliest days when the machines filled rooms and researchers had to write their own programs.

At the University of Missouri, the College of Agriculture not only had a role in operating the very first computer on campus, it was among the first to develop the device as a tool to improve weather and climate forecasts. And it was a CAFNR professor who wrote one of the first books describing how to use the computer as a legitimate research tool.

Science Fiction Comes to Mizzou

The first computer on the MU campus was switched on in 1961 as a joint effort by Engineering, University Extension and the College of Agriculture to predict electrical use in Missouri’s 114 counties.

Individual electrical companies in the state had consolidated shortly before, and a new way to realign the consolidated grid and estimate load growth was needed to create a more efficient system. To complete these calculations manually would have taken months.

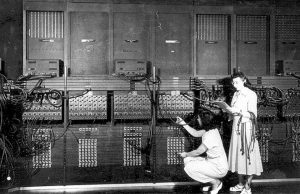

Six regional transmission cooperatives in Missouri financed the $97,000 machine ($774,000 in today’s inflation-adjusted dollars) and asked the MU consortium to operate it. The electro-mechanical, pre-transistor Westinghouse Network Calculator filled a room and used hundreds of vacuum tubes. Five people (two administrators and three engineers) were needed to operate it. The computer had all of 28K of computing power, less than a pocket calculator bought at a dollar store has today.

Taking Computing Into the Sky

While the first computer on the Mizzou campus was that Westinghouse unit, it was not the first computing on campus. That honor goes to the Missouri Agricultural Experiment Station.

In 1947, the College of Agriculture established a climate project in the station. Instigated by College of Agriculture Dean Merritt Miller and Associate Dean Samuel Shirkey, it operated as a collaborative enterprise with the U.S. Weather Bureau to record climate records for selected Missouri weather observing stations.

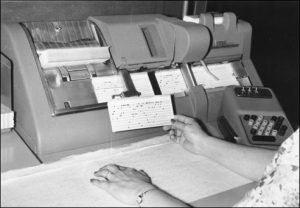

Initially, Harold McComb, meteorologist-in-charge of the Columbia Weather Bureau, took observer forms and punched their data onto cards that were then transported to the weather bureau’s computer processing center in Kansas City.

Each punch card was a stiff piece of paper that communicated commands or data through the presence or absence of holes in predefined positions. Each card, usually punched on a machine with a keyboard operated by an administrative assistant, could transfer up to 200 bytes of data. It took stacks of these cards to communicate anything meaningful.

In 1949, the MU College of Agriculture established a professional research position in climatology. Wayne Decker, assistant professor, took over duties to key punch in climatic records as well as establish a teaching program.

Early in 1951, McComb and Decker had enough data for the Agricultural Experiment Station to publish a series of climate-related bulletins. These bulletins not only described the historic patterns of precipitation and temperature across the state, but also presented “risk statistics” intended to predict Missouri weather patterns.

Establishing the Computer as a Valid Research Tool

Beginning around 1970, James McQuigg, professor of atmospheric science at Mizzou, used a similar process to experiment with mathematical models of weather and climate forces on the hemisphere scale. In those days there were no off-the-shelf programs, so McQuigg had to code the software himself. McQuigg initially used the weather service’s computer, but switched to MU mainframes as they became operational.

McQuigg used what he found to introduce the idea of a computer weather simulation as a cost-effective alternative to long-term field experimentation. He also suggested that such predictive methods could be used by the power industry to better forecast daily temperature and daylight levels, allowing them to create only the electricity needed for the day. He did the same thing to help road construction companies to better plan temperature-sensitive paving.

McQuigg not only used the devices, but in 1970 co-wrote a book, “Flowcharting.” It was one of the first books to provide evidence points on how the computer could be used as a legitimate scholarly tool.

Sharing Mizzou’s Mainframes

“I remember the computing situation when I arrived in 1976,” said Stephen Mudick, professor emeritus in atmospheric sciences. “Everything was done on a mainframe computer. You wrote your own programs – I used Fortran – on punch cards. We submitted our card decks at the computing center. Later, we returned and picked up our printed output. With that we made our contour maps. Later, the punch cards were replaced by data storage on magnetic tape, big reels about a foot across.”

That magnetic hard disk data storage consisted of 50 double-sided, two-foot-diameter disks, which stored about five megabytes of data.

“Mizzou’s mainframe was housed in Lefevre Hall,” Mudick said. “I also remember a shed behind the Math building that had punch card machines. We later had card punch entry machines in atmospheric sciences, although we quickly advanced to terminals whereby you could directly type in data.”

Early Research Into Plants and Weather

McQuigg also developed a computer program to handle vast amounts of data to analyze crop and climate reports back to 1890. His statistical research, mentioned in an April 1976 New Scientist story, found that it was good weather, not advances in seed and fertilizer technology, which raised yields.

McQuigg and his computers became known internationally for expertise onthe economic impacts of weather and climate. In 1970, he was designated as the first Research Meteorologist for the Environmental Data Service, NOAA. As a federal researcher he continued to work on the campus of the University of Missouri.

After retirement, McQuigg set up a rent-by-the-hour computer lab at 310 Tiger Lane to offer students access to word processing to write theses and dissertations, putting computer technology into students’ hands for the first time.