From the 1862 passage of the Morrill Act establishing land grant colleges of agriculture to well into the 20th century, the University of Missouri College of Agriculture was front-page news. Not in a good way.

From passage of the act until 1870, a fierce debate raged on where to put the new college. Every state legislator wanted it in his district and vehemently opposed any other location. The debate was so lengthy that Missouri was in danger of losing the Morrill Act windfall entirely. When MU got the College in a political compromise, the $350,000 Morrill Act endowment dwarfed the $180,000 endowment for the University. When the majority of MU faculty members turned up as ag faculty (including literature, philosophy and history teachers), Missouri legislators charged hanky-panky in funds allocation. From there it got uglier. The College’s first Dean was fired by the Curators who did not like his complaining about a lack of money. The College’s second Dean was fired by the Legislature who though he was too fiscally cozy to the University. All the while, legislative bills were written to separate the College from MU and move it to another part of the state.

Into this maelstrom came the third Dean. He isn’t remembered with a building at Mizzou (as the first, fourth and fifth Deans) or a research field (the second). In fact, very little information about him exists in MU archives. Yet, he probably was pivotal in ending a decades-long argument over the College and put it on a course of research, teaching and service that is recognizable today.

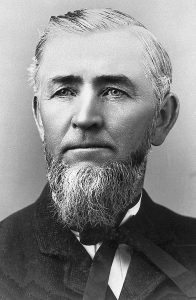

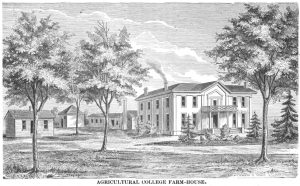

Edward Porter (1829-1895), third dean of the MU College of Agriculture, led the College just six years (1889-1895) when he died of a heart attack in the Agricultural College Farm-House on the College Farm near where Eckles Hall now stands.

Porter Helps Delaware Earn Land Grant Status

Porter was born Aug. 29, 1829 in Vermont. Before entering college, he spent eight years on a stock and dairy farm. He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1851, valedictorian of his class. Porter earned his master’s in civil engineering from the school in 1854. Though adjutant-general for the State of Delaware, Porter served as a private in the infantry during the Civil War, insisting on a combat assignment rather than administrative service.

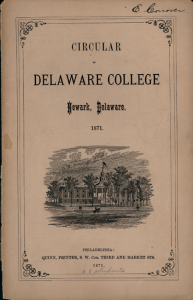

After the war, Porter joined the respected but financially troubled Delaware College (now University of Delaware) as a professor and administrator. The Morrill Act presented the threadbare college, that existed on student fees only, the opportunity of a sudden endowment of 90,000 acres in 1867.

Porter, who owned a dairy farm east of Newark, was probably the closest person with ties to agriculture that the liberal arts college had. He was promoted to Professor of Practical Agriculture and Natural Science and given the task of reorganizing the institution as an agricultural college to capture the Morrill Act money

The need for funds was acute. By September 1870, the college’s original endowment shrunk to just $2,500 – against $4,000 in repairs, a $2,000 salary for the college president and $1,000 per year for each full professor. Income was meager. Though the tuition fee had been raised to $60 per semester (it was $40 in 1865), students given “legislative scholarships” didn’t have to pay anything.

Porter’s new “Graduate in Agriculture” course didn’t help bring in any money. According to the University of Delaware official history, “no one ever took it.” Porter did establish an experimental farm of truck gardens, vineyards and orchards that provided some income (the land was Porter’s on loan to the college).

But Porter’s empty agricultural classes and farm were enough to qualify Delaware College as the state’s Land Grant university. Funds from the sale of the Morrill Act acreage were only a modest boost, however. Delaware’s land sold for just 89 cents per acre in the post-Civil War recession (Kentucky got only 50 cents an acre), yielding $83,000. At six percent interest, Delaware College had a Morrill Act annual endowment of just $4,980.

In 1872, Porter was asked by the college administration to travel to Dover to lobby for a legislative bill that would establish an annual appropriation for the college. He was successful. Today, the University of Delaware considers Porter as one of its founders.

Agriculture at Delaware College was still not successful. The history of the University of Delaware states:

Unfortunately, no one could say an encouraging word about the development of agriculture at Delaware College. Edward Porter was surely a satisfactory man to be in charge of the program; his later success at Missouri is proof of that. But students were not interested.

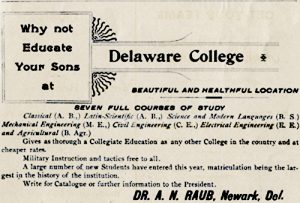

Porter kept trying. He printed 1,000 flyers to attract students. The college authorized $100 for Porter to travel the state by horse and carriage to advertise the agricultural program. Porter and the college even gave prizes to promising youngsters who produced bumper crops of corn.

In 1881, the civil-engineer-turned-agriculturalist threw up his hands and accepted a position as Professor of Agriculture at the University of Minnesota, where he was named the first Director of the Experimental Station there. In honor of his accomplishments, Delaware College gave Porter an honorary doctorate.

The University of Delaware history states that the college probably overworked Porter. He served as an administrator, trustee, and professor of agriculture, math, physics, civil engineering and military science. He had, the history reports, “taken on too much.”

Missouri’s State of Dilapidation

After the firings of the first two College of Agriculture deans, the University of Missouri needed an able administrator to salvage agricultural education. They zeroed in on Porter.

In his 1944 book The History of the Missouri College of Agriculture, Frederick Mumford said Porter came to MU in 1889 and found the College of Agriculture in disarray with only nine official students – a number that would slump to six in 1890 – and a dozen paid faculty teaching such “farm courses” as literature.

Fueling legislative anger was an inventory of College assets that showed its farms and buildings were in a “woeful state of dilapidation” even though the College had paid the University $209,896 ($5.2 million in inflation-adjusted dollars) from Morrill Act and state legislative funding.

Dean Porter’s first report to the Curators in 1890 was blunt and listed the reasons why the College was failing: its (and MU’s) organizational structure was defective, the course of instruction was too theoretical, the six-year time to get an undergraduate degree was too long and expensive, the quality of instruction was too low, and there was a lingering opinion by farmers that the College was founded solely for their benefit and that they should control it.

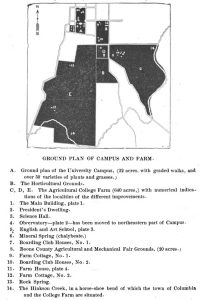

Porter charted a new direction: change the organizational structure, alter the College curriculum to meet the academic demands of the masses, make the term two years rather than six, make coursework intensely practical, and “keep students associated with farm life and manual labor.” Porter also recommended that College of Agriculture buildings be built near to, but separate from, the University (ultimately resulting in the famous red and white MU campuses).

At a meeting at the Monroe House in Jefferson City, farmers, faculty members and legislators argued over Porter’s plan. The discussion was overshadowed by a legislative committee report damning the University for failing to maintain agricultural properties despite the College paying the University the $209,896.

When it was revealed that the College still owed the University $72,512 ($1.8 million in today’s equivalent dollars), an angry legislative committee again recommended splitting the College from the University, moving it to another part of the state, and running it as an independent entity where students could gain practical knowledge of farming by working on the Experimental Farm (and being paid 10 cents per hour). This legislation became known as the Murray Act.

The Missouri Attorney General stated that for such a separation to occur, the state’s Constitution regarding the Board of Curators’ charter would have to be amended (a point that killed an earlier bill to separate the College and University). A legislative committee promptly started on that project.

The continuing argument was having an impact on ag faculty who were giving up and leaving. In 1892, professors Thomas Jefferson Lowry (Lowry Mall is named in his honor), Howell van Blarcom and J.P. Blanton moved to other universities. John Waldo Connaway (Connaway Hall), who had become famous for identifying the cause of Texas Tick Fever plaguing Texas-Kansas cattle drives, left, too, as did Professor Henry Waters (Waters Hall).

1894: The College’s Course Changes

Despite these setbacks, Porter made steady progress, Mumford stated. In just two years, a new audit showed the College Farm was now in good (almost model) condition. Changes in the curriculum made a MU agricultural education more appealing. In 1894, there were 83 regular and 148 special agriculture students enrolled.

The respected Connaway was persuaded to return to MU, a big boost to its sagging reputation. Nine new faculty were added (and six more in 1895).

Dean Porter drilled right into the biggest contentious problem and made his solution stick. He administratively separated College of Agriculture faculty from the University faculty – effectively meaning that Morrill Act money stayed in agriculture. This was a gutsy and significant move to blunt the legislative effort to divorce the College from the University. (Porter’s gambit was successful. 1895 would be the last year the Legislature tried to separate the College of Agriculture from Mizzou.)

Porter also made sure the College was seen as being responsive to the needs of farmers. He established a weather bureau and crop reporting service. His practical and useful short courses offered to farmers during their off-season built bridges to a constituency who were most critical of a MU College of Agriculture. Acting on the mandates of the 1887 Hatch Act, he began to form experimental farms in various parts of the state to focus on unique regional needs. He worked with farmers to discuss the best locations. This idea evolved into CAFNR’s Outstate Research Centers.

Dean Porter, however, was a sick man. In November 1894, he suffered a heart attack and was unable to work. In December, Ag Chemistry Professor Paul Schweitzer (Schweitzer Hall) was appointed Acting Dean. Porter died at the College Farm-House on Jan. 5, 1895 at the age of 66 years. Newspapers of the day praised his efforts to mend the long-running acrimony plaguing the College, University and Legislature, and blamed overwork for his death.

The Missouri Legislature prominently noted his progress in fixing the fiscal and academic problems of the College. Though an undercurrent of dissatisfaction still existed among farmers, the Murray Act was narrowly defeated in the Senate. Dean Porter’s successes at making “a real College of Agriculture” that could work within the University structure was cited as the primary reason for the defeat, Mumford wrote.

The Board of Curators knew they had to select a new Dean who could build on Porter’s progress. That person would be unique – an actual graduate of the University of Missouri College of Agriculture.

No building, field or program at Mizzou honors Porter. In the 1895/1896 Catalogue of the University of Missouri, no mention of his death was included in remarks by C.M Woodward, president of the Board of Curators. Porter and his wife are buried under modest headstones at the corner of Gordon and Todd in the Columbia Cemetery.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Since this story was published, additional information on Edward Porter is now available courtesy of his great-great nephew, James Porter.

James reports that his great-great grandfather, Charles Eugene Porter, was Edward’s younger brother. When the Civil War began, Charles left their home in Newark, Delaware to join the Confederacy in Virginia. Family history states that Edward and their father strongly disapproved of his decision. Based on letters that Charles wrote, neither communicated with him during the war. Charles served as a private in the C.S. Army and later as a gunnery officer in the C.S. Navy.

Professor Porter had three daughters. Only the youngest had children. She married to one of her father’s students, Andrew McNairn Soule, who had an esteemed career in agriculture himself. Soule served as Dean of the Agricultural Department, Virginia Polytechnical Institute, Blacksburg, Vir. (1903-1906); Director of the Virginia Agricultural Experiment Station; and, finally, as President of the State College of Agriculture at the University of Georgia.