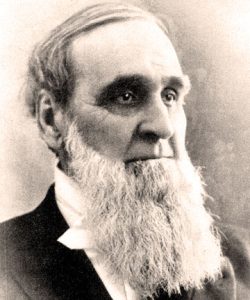

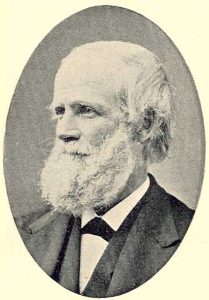

George Clinton Swallow (1817-1899), the first dean of the Missouri College of Agriculture, was no crop or animal expert, but a geologist. If he harvested anything, it was controversy. It dogged his heels from Massachusetts to Missouri, Kansas and Montana.

His ambition and inability to back away from a fight may have been just what MU’s new and severely underfunded ag school needed to get its tenuous start. It would end roughly for him, however.

Swallow was born in Buckfield, Maine. His father was a farmer and blacksmith too poor to send his son to college. That didn’t stop Swallow. At age 16 he began teaching fellow farm kids to read and earned enough money by 1839 to study chemistry, mineralogy and invertebrate paleontology at Bowdoin College. He graduated with high honors.

From graduation until coming to MU seven years later, Swallow taught various grades in Maine and Massachusetts. Leroy Page, who penned a Swallow biography for the Kansas Academy of Science in 1996, paints the young teacher as a man of strong convictions, attending and leading temperance and abolitionist meetings.

Swallow was also very serious about teaching – something that dumped him into his first pot of hot water. In fall 1840, Swallow went to his School Committee and inquired what was to be done with boys who didn’t pay attention. They told him to “whip to the extremity.”

The next day Swallow did just that. When a young Irish lad accused of swearing refused to take his jacket off for a paddling, Swallow “whipped him severely about 30 times” with a green leather horsewhip. The Irish population “was on fire with rage,” Page reported, and Swallow was taken to court. After much legal maneuvering during the following five months, Swallow settled without a trial. The affair had cost him $80, a rather large sum, and his job, Page wrote.

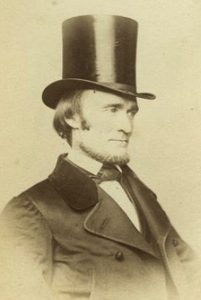

In 1843, Swallow moved on to become the principal of the Brunswick Female Seminary, a post he would keep until 1849. He then joined Hampden Academy in Maine where he met Hannibal Hamlin, future U.S. senator and first vice president under Abraham Lincoln. The two formed a plan to create a school of agriculture and science with a laboratory in agricultural chemistry and geologic assaying. Eventually, the idea would be endowed by the state with a grant of land. This was the prototype for the Morrill Act signed into law by Lincoln in 1862 that established a network of agricultural land grant colleges.

A Cold, Snowy Trip to Mizzou

Swallow was appointed chair of chemistry and geology at the University of Missouri in October 1851. He left snowy Maine for Missouri on Dec. 8, leaving his pregnant wife and three-year-old daughter. After a “very muddy & cold & wet” journey, he arrived on the St. Louis to Columbia stagecoach on Dec. 30 and began work the next day.

Swallow didn’t stay long at MU. He resigned in 1853 to become Missouri’s state geologist. The appointment was controversial – many St. Louis newspapers accused him of being unknown to Missouri and less qualified than local candidates.

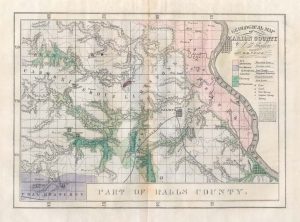

Swallow began work on a geological survey by boat from Council Bluffs to Columbia, traveling 600 miles in 52 days. He and his team surveyed five miles each side of the Missouri River banks, collecting thousands of specimens of soils, minerals and rocks. Other journeys followed.

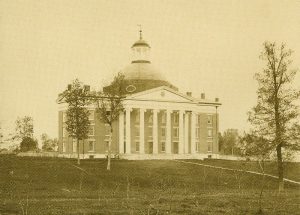

In 1855, he published two reports praised by geologists in America and abroad. By 1860, Swallow would publish 33 such reports covering 80 Missouri counties. Many of his samples and observations, unfortunately, would be destroyed in MU’s Academic Hall fire of 1892.

Swallow’s time as a geologist in Missouri was contentious, according to his Kansas Academy of Science profile. Paleontologist F.B. Meek in 1858 charged Swallow with stealing credit for the discovery of Permian fossils in North America. A bitter and public feud developed that, perhaps, led to Swallow’s rejoining MU as a professor in 1857.

Dangerous Days Before the Civil War

Swallow was a discrete but resolute abolitionist in a state where slavery was strong and opposition to it dangerous.

In the fall of 1857, Swallow failed in his effort to be elected president of the university. He then led a faculty movement to eliminate the office of the president and make professors directly accountable to the board of curators.

During this time Swallow engaged in a lengthy and ugly newspaper argument with Caleb Stone, a strongly pro-Southern member of the board of curators who opposed Swallow’s faculty plan. Stone accused Swallow of being an abolitionist – a charge Swallow felt he had to deny in those tense times. On the eve of the Civil War, Swallow failed re-election as a professor on a vote of 7 to 6.

Swallow had earned the nickname as “the Border Ruffian Savant” as early as 1856 because of his financial support of free state activists. According to one critic in 1864, Swallow “gloried in the name.”

In February 1862, while Mizzou was closed due to the war emergency, Swallow was arrested in St. Louis on a charge of disloyalty – probably on evidence of letters sent by his enemies in Columbia. His maps and geological papers were briefly considered proof he was a Confederate spy. Swallow was released within a week after taking a loyalty oath and giving a bond of $5,000. One character witness was artist George Caleb Bingham. In November 1862, Swallow was confined in a military prison in Columbia as a Confederate spy, but was released unconditionally in January.

Kansas, Montana and Back to Missouri

Swallow must have had enough of Missouri. In 1864, he was back in Kansas as a candidate for state geologist, a post he didn’t get because of old accusations of disloyalty.

The new state geologist, B.F. Mudge, appointed Swallow state paleontologist. Page wrote that Mudge later claimed Swallow sabotaged his work to succeed him. In 1865, Swallow was appointed Kansas State Geologist – a post now with no budget as the legislature was tired of the bickering.

By 1866, Swallow was on the move again – this time to Montana. He was appointed Superintendent of the Highland Gold Mine in 1869 with a kingly salary of $5,000. He supervised construction of a quartz mill and opened new mines. There, he became part of a dispute with state geologist Albert Hager. It got personal, again – Swallow telling the governor that Hager was a “thief and a liar.”

In 1870, Swallow returned to the University of Missouri to become chair of both the Natural History and Agriculture departments. Though infamously controversial, Swallow was a significant academic catch for the struggling University of Missouri. He was a man of many skills — a professor of geology, chemistry and even medicine (a degree he obtained in St. Louis while he waited out the Civil War).

In 1870, he was appointed as the first Dean of the MU Agriculture and Mechanical College. A whole 15 students signed up for courses that first year, according to the History of the Missouri College of Agriculture written by Frederick Mumford in 1944. Mumford said Swallow had great plans for the new college, but was hampered by a lack of funds.

Great Difficulty

“Dean Swallow’s administration was one of great difficulty,” Mumford wrote. “On one hand, he was subjected to constant criticism by farmers for failing to provide equipment, teachers and investigators [to the college]. On the other hand, authorities from the university would not provide him facilities essential for this.” Mumford wrote that Swallow had no textbooks, established course of study, farms or orchards, domestic animals or farm equipment, or even a classroom. He had few skilled faculty capable of even teaching agriculture.

Mumford said Swallow also had to fight the opinion of “the aged and influential” who were fixed in the idea that no college education could be made practical to farmers. Swallow complained bitterly and loudly about the lack of university support. An exasperated curator referred to Swallow as “that fork-tailed bird from Maine.”

In 1875, Swallow tore into a MU promise of $10,000 in funds for teachers and equipment that was reduced to a mere $375. Swallow blamed a reduction of enrollment in agriculture from 138 to 15 on the miserly university administration. “Our students saw apparatus and books pouring into other departments and saw their department left destitute,” he said.

Swallow’s angry outburst did cause the university to direct more funds to education in agriculture. In 1877, the Missouri legislature helped by allocating more money and making Swallow a member of a new state Board of Agriculture – a message to the university that the state considered agricultural education important even if the university did not. In 1879, a new experimental farm was cultivated for the first time.

But Swallow’s sharp ways created a squadron of detractors. Former MU president Daniel Read wrote in 1877 that Swallow was a “schemer, who boasted of his power over president Samuel Laws.” Benjamin Thomas, professor of physics, called Swallow a “political wire puller.”

Swallow’s end at MU began when he insulted Laws by ruling the president out of order during a heated faculty meeting over money. Laws ignored Swallow. Rebuked, Swallow appealed to the faculty who overruled him by a unanimous vote. The board of curators found Swallow had little support among the faculty and demanded his resignation. Swallow refused and the board declared his position vacant in June 1882.

Final Years

Swallow went back to Montana. From 1882 to 1890, he served as the editor of the Helena Independent newspaper and state director of mines. He died in poor health in 1899. He was buried in Columbia, probably the closest place the wandering academic could call home.

The feisty Dean of Agriculture would get the last word, however. In 1927, a granite boulder was placed on Swallow’s grave by former students who fondly remembered him for his aggressive support of their educations.

Legend states the students originally wanted to erect a memorial spire taller than the monuments for the MU administrators who had treated Swallow so poorly. Cemetery officials refused the request saying deans shouldn’t eclipse chancellors and presidents, so the students dumped the unique bolder in the spire’s place. Swallow was, one student at the time said, “a gentle friend and dangerous adversary.”

In 1930, Swallow Hall, now the home of the Department of Anthropology, was named in his honor by the university which fired him. Today the University of Missouri is extensively renovating that building.