In 1885, in a move that newspapers of the day decried as a cynical grab for Morrill Act money, University of Missouri President Samuel Laws merged Mizzou with the supposedly separate new College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts to create the Missouri Agricultural College and University. The union, which survived only a few months, triggered angry outbursts by students, heated newspaper editorials and reprisals by the state government.

The hot reaction caused Laws to quickly make the College a division of MU, but that didn’t stop the furor. An angry Missouri Governor called for ag’s removal and relocation from the University. The Legislature targeted the College’s second dean for dismissal to made sure that monies intended for the College went to the College, even if that action wasn’t exactly legal. And President Laws was fired over an elephant.

The affair is considered one of the most bizarre in MU’s history.

A College Richer Than Its University

The prelude to the whole thing was money. The MU College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts was founded in 1870 with an endowment of approximately $350,000 from funds generated through the Morrill Act. This compared to an endowment of just $180,000 for the entire University.

The Morrill Act specifically called for the new colleges of agriculture not to be added to existing universities but be separate institutions, thus creating Kansas State University apart from the University of Kansas, for example. In a Missouri Assembly political compromise, MU founder James Rollins got around that stricture by claiming the agriculture and liberal arts schools would be adjacent to each other.

Agricultural interests were unenthusiastic about the new College being that close to the University. MU was considered too oriented to the classical arts. Farmers wanted an independent school run by agriculturalists. Farmers and some in the Legislature worried that MU was more interested in Morrill Act funds than growing a robust college of agriculture.

The College’s first decade at MU was a long and bitter argument over funding that resulted in the firing of its first Dean, George Swallow. In his 1944 book The History of the Missouri College of Agriculture, Frederick Mumford said there were persistent rumors that the University was chronically underfunding the College when its second Dean, Jeremiah Wilson Sanborn, took over in 1882.

Despite the rumors, the Missouri Assembly moved in to grow the College. In 1883, they appropriated $23,000 to the College to expand. That money produced results. Eight scientific bulletins were published by ag faculty, earning the praise of the St. Louis Journal of Agriculture that called them of utmost importance to farmers of the West.

Colman’s Rural World magazine in 1884 celebrated “the patient, plodding and hardworking dean…Professor Sanborn, who has been in possession but only two years, took hold of a farm of about 800 acres with very positive ideas how it should be done and what should be done with it.”

In 1885, Dean Sanborn reported a profit of $1,280 from the Agricultural Farm. Missouri Governor Thomas Crittenden lauded Sanborn and the College. As a way to expand the College’s success, he created the Office of State Veterinarian and directed that its work be part of the College. Also in that year, the State Board of Agriculture recommended the establishment of a new Experimental Farm.

Even the University, which valued liberal arts over prosaic stuff like agriculture, was impressed. President Laws gloried in the College’s new importance – and the fact it was rolling in dough. His attention was a harbinger of what came next.

Surprise Name Change and the Reaction

Mumford wrote that Laws, apparently on his own volition, changed the MU catalog’s name to the “Forty-fourth Catalogue of the Missouri Agricultural College and University.” Newspaper editors, farmers and legislators were shocked and could only speculate about the sudden, unilateral and unannounced name change. Some wondered if the University had finally recognized that seeds were more important than Socrates. Most thought it was a sneaky tactic allowing the University take all of the Morrill Act funds allocated to the College.

Whatever the reason, a storm of protest erupted. A special committee of the Legislature was appointed to investigate.

On the day the committee arrived in Columbia, 200 University faculty and students staged a noisy parade with a threshing machine, cow bells, wheelbarrows and satirical signs labeled “Military Agricultural Students,” Academic Agricultural Students” and “Theological Agricultural Students.”

“A Student” wrote to The Kansas City Times newspaper that the University had been turned into a farm and some loose accounting was taking place. He said the catalog stated there were 349 students in the Agricultural College while the real number was only 11. “The students [of the University] desire to let the public know that they have supreme contempt for that miserable farce known as the Agricultural College….”

Mumford wrote that Laws never fully explained his unilateral name change. Newspapers of the day filled that void – it was the money.

The Columbia Missouri Statesman newspaper claimed it obtained the Missouri Legislature’s unreleased internal report. It said that “one discovery followed on the heels of another…that revenue from the land’s fund [Morrill Act] had been mingled with the University funds and not for the Agricultural College as required by terms of the grant of land. Various sums of money properly belonging to the farm have been misapplied.”

The paper also reported that only two professors hired as agriculture teachers really taught the subject – the remainder were attached to literary units.

The Iowa State Register newspaper claimed that the University “swallowed three-fourths of the original endowment illegally.” The Secretary of the Missouri State Board of Agriculture agreed: “The Agricultural College has been a great sufferer…on account of the association [with the University]. Not half of the income from the income of its fund derived from the government is used in accordance with the law.”

St. Louis and Kansas City papers were incensed, too. They demanded the Legislature separate the Agricultural College from the University, putting the College’s governance in the hands of the State Board of Agriculture.

President Laws quickly backpedaled and agreed to return to the old hierarchy. He promised a clear division of funds that would be monitored by outside auditors.

The Legislative committee’s final public report recommended not separating the College from the University, stating that such a move would be costly and disruptive. It did recommend a monitored separation of funds, even as it sidestepped the charge of misappropriation of Morrill Act money.

The committee also allocated $24,750 in additional funds to the College, paid to the treasurer of the State Board of Agriculture who would disburse money directly to the Agriculture Dean. Mumford reported that the provision “was clearly a protest against the administration of the University, [even though] it was wholly illegal and could have been opposed in the courts by the Curators.”

In an 1887 meeting of the Board of Curators, members stated officially that the Agricultural College was a unit of the University, not a separate entity, and said that income from the Morrill Act would be kept in a separate account and used for no other purpose than for the growth of agriculture.

With that, everyone hoped the imbroglio would go away.

Agriculture’s Second Dean is Fired

The controversy wasn’t going to die so easily, and the College of Agriculture’s hardworking Dean Sanborn was getting a good part of the continued criticism. Dean Swallow railed against poor funding of the College and was fired for it. Dean Sanborn was seen as complaining too little.

The Iowa State Register newspaper called Sanborn “a noble man, but he is tied to the University.”

“There was a growing feeling that Sanborn might not be the right man,” Mumford wrote. “[Supporters of the College] began seriously to doubt his qualifications as Dean.”

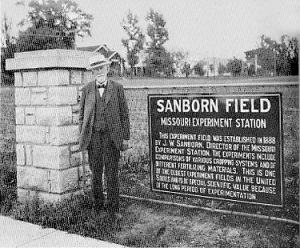

Passage of the Hatch Act in 1887 – that established an MU Agricultural Experiment Station with a $15,000 a year endowment – should have been the opportunity for Sanborn, Mumford reported. Sanborn was “more of an experimenter than a teacher.” He was the logical candidate as Director of the station, but the position was awarded to Paul Schweitzer.

The ag chemistry professor held the position a year, when Sanborn, controversy finally waning, was named Director. “He, thus, was the first in Missouri to have the double title of Dean and Director, and this title has been held by every Dean [since],” Mumford wrote. This period was a brief respite for Sanborn. His last act at MU was about to be written.

Money, Again

In spite of the scrutiny of the Legislature and agriculture interests, the Chairman of the Board of Curators made himself Business Manager of the Experiment Station – with a healthy salary – and brought in his son as Secretary. The son of another Curator was made an agriculturalist of the station, prompting a new storm of protest. The Curators and sons in question resigned, but that wasn’t enough.

In January 1889, a fed up Governor Albert Morehouse addressed the Legislature and said it had been a mistake to ally the Agriculture College with the University and demanded a divorce. He requested, and got, a joint committee to figure out how to do just that. “Educating and training students for the practical pursuits have not and will not be the success they ought to be as long as the present state of affairs exists in Columbia,” Morehouse thundered in the statehouse.

The Columbia Missouri Statesman newspaper added that it was time for heads to roll: “Hundreds of representatives…are of the opinion that the President of the institution and the Dean of the Agricultural College have outlived their days of usefulness. The feeling against them is quite apparent.”

The committee reported in April 1889 that it was unconstitutional to separate the College from the University – the College of Agriculture was stuck in MU. The committee could, however, direct its anger at Sanborn, accusing him of failing to stop misuse of Morrill Act funds and standing idle as Curator sons packed the Experiment Station. “We recommend he resign at the end of the present collegiate year, and if he does not resign his office be declared vacant and his successor elected,” the report stated. To make the recommendation stick, the Missouri House of Representatives withheld its appropriation of $67,300 to the entire University until Sanborn was gone.

Laws resigned in May. He had been grilled by the Legislative committee over the name change and funding controversy. Yet, it was his purchase of a dead circus elephant that created the most ire (see photo above). He moved to Kansas City to write books.

Sanborn was summoned to a meeting of the MU Curators on June 12, 1889. The Kansas City Times reporter there said Sanborn was “game as a fighting cock” and showed “stiffness about his backbone.” He left the meeting demoted to professor.

Sanborn soon left Missouri to become the first president of the Agricultural College of Utah, a post he would hold until 1894.

A month after the firing, Edward Porter, credited with helping establish the modern University of Delaware, was appointed the third Dean of the MU College of Agriculture. He would face, and solve, the problems with the University and money.