Wildlife behavioral patterns have been tracked by researchers across the United States for years. While many individual research studies have been done on this topic, a snapshot of the United States as whole, has not.

Summer LaRose, research wildlife biologist at the University of Missouri (MU) in College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources (CAFNR), participated in a nationwide study tracking wildlife pattern. The paper was titled SNAPSHOT USA 2019: A Coordinated national Camera Trap Survey of the United States.

“This survey opportunity came up through the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences,” LaRose said. “I have always wanted to camera trap at the Horticulture and Agroforestry Research Center (HARC), in New Franklin, Mo. I was working at HARC at the time doing crop breeding, but I had always been interested in wildlife. I had always been curious on what type of wildlife were out at HARC. When the Natural Sciences Museum sent out a call for participants for this survey, I decided to sign us up.”

The SNAPSHOT USA project was a collaborative survey of terrestrial wildlife populations. Data was collected by camera traps that were in all 50 states. SNAPSHOT USA is a large data set that anyone can access to learn more about mammal populations nationwide. LaRose said this paper is the first ever to combine data on mammal populations nationwide. Previous surveys like this have been done with birds and amphibians, but never for mammals.

“Ornithologists and other researchers use these existing data sets all the time. It is a good resource to have with all of this data in one place,” LaRose stated. “Nothing like this has been done for mammals because mammals aren’t as easy to see like birds or amphibians.”

The SNAPSHOT USA database included more than 1,509 camera trap sites across 110 camera trap arrays. The number of cameras that were on each site varied from four to 49. Data collection began on August 27, 2019 and lasted until November 24, 2019.

North Carolina Museum of Natural Science sent specific protocols in which participants had to follow. Cameras needed to be set a certain length apart and the researchers had to classify the environment in which they were collecting data. Environments ranged from more urban areas to completely wooded, wildlife heavy.

University of Missouri contributed data by setting their traps at HARC. Fifteen cameras were set at HARC. Following the proposed protocol, cameras were placed approximately 600 feet but not more than 3 miles.

“HARC has a unique landscape in that it’s wooded, but there is also farmed land. It was fun to see the different species that are wandering the property. Some in which we were shocked to find,” LaRose said.

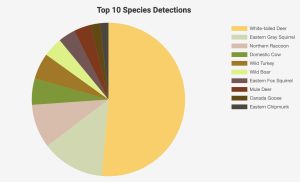

The main mammal identified was white-tailed deer. Other species included squirrels, coyotes, racoons and opossums. One sequence caught river otters. The data collected at HARC was used to look at activity patterns for each species. The environment is so diverse, LaRose and CAFNR undergraduate student Harrison Stoudt looked at the interactions between the different species.

For example, they looked at the interaction between deer and coyotes, to see if they change behavior when around one another. When the data was collected, fawns at this time were still young, which make them vulnerable to coyotes. By analyzing the data, they can try to figure out if deer are doing anything behaviorally unique to avoid coyotes more during this time than during another time of year.

When traps were checked, each mammal in the image was identified. After the initial verification, all the data were uploaded to eMammal Data Management System, the data management system and archive for camera trap research projects.

The overall study sampled wildlife at 1,509 camera trap sites, representing a variety of different regions including forests, grasslands and deserts. This effort resulted detections of 83 species of mammals and 17 species of birds.

Data was collected for 2020, MU also contributed to this effort. The 2020 paper has not yet been released to the public as lead researchers are still working through compiling all the data.

“We have been using camera traps in wildlife biology for years,” LaRose said. “Many researchers have used them for individual studies to track patterns. When doing an individual study, it can be difficult to see if that particular pattern is replicating elsewhere. Having this large data set is super helpful for researchers to refer to.”