In a small town in northwest Missouri, a small farmhouse without electricity and running water stood against the rural landscape that was the Litton Charolais Ranch. This was the childhood home of Jerry L. Litton, the successful cattle rancher and United States Congressman – and the namesake of the Animal Sciences Research Center, known to few as Litton Hall.

Litton attended high school at Chillicothe High School, and during his time, he was president of both chapters of the National Honor Society and Future Farmers of America (FFA) – now the National FFA Organization. Through FFA, Litton began sharpening his public speaking and leadership through contests and other agricultural service activities. His first FFA project, helped by his father, consisted of two Duroc gilts, one steer, two registered Hereford heifers, and 60 acres of corn on rented ground.

Upon his graduation, Litton enrolled at the University of Missouri College of Agriculture and graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in 1961.

After graduation, Litton entered into partnership with his parents in the successful Litton Charolais Ranch, and started using state-of-the-art breeding technology and keeping statistics on the health and breeding records of their cattle through use of computers in the barns.

“This is an early example where a cattle producer was so interested in data collection that genetic progress was achieved and herd selection refined,” says Bryon Wiegand, director of the Division of Animal Sciences.

This pioneering dedication to data and estimated breeding values set the course for what we know today as expected progeny differences (EPDs) – one of the most important tools livestock producers use in herd health and management, Wiegand said.

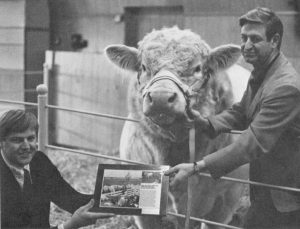

Litton and his family wanted to showcase the superior rates of gain and genetics with Charolais-cross cattle, but at the time, there were no classes that permitted this breed to show. However, with some persistence, the white cattle that most people in the Midwest had never seen were garnering national attention – grand champion banners and ribbons. The Littons sold their Charolais cattle around the world and established a stellar reputation as cattle breeders.

Although the lives of Jerry Litton and his family were tragically cut short in a plane crash on the night of his primary election victory in 1976, his legacy lives on through the Jerry Litton Family Memorial Foundation. The Animal Sciences building on campus at the University of Missouri bears his name on a bronze plate as a posthumous honor for his revolutionary work in cattle genetics.

The Foundation’s mission helped establish the Jerry Litton Fund for Agricultural Leadership at the College of Agriculture, Food & Natural Resources, which facilitates and funds the Litton Leadership Scholars program.

“Learning how Mr. Litton turned his family farm around by using animal science is truly amazing. By documenting traits that were never really looked at, and by constantly experimenting on new ways to raise cattle, he made Charolais a recognized name in the cattle industry in the Midwest,” says Ryan Chapski, animal sciences sophomore and current Litton scholar.

The Foundation continues to promote the leadership, integrity and perseverance that Litton was revered for.

“As an animal sciences student, Litton Scholar, and a Missouri farm kid, I found that Jerry Litton’s life was incredibly inspiring,” says Madi Ridder.

“He was able to do constant research and development on his herd of Charolais cattle, which led him to being the kingpin Charolais breeder in the state of Missouri. He was always busy working on something new, but never too busy for showing others how grateful he was for them.”