Rebecca North, assistant professor of water quality in CAFNR’s School of Natural Resources, learned and lived by a paradigm commonly accepted among limnologists around the world — “blooms like it hot” – meaning that water temperatures must be warm for algae blooms to develop. But, a recently published study co-authored by North could dismantle this long-held belief.

“You only take on big ideas – when you seek to take down paradigms – when you have collaborators from all over the world,” North said of the study team that consisted of researchers from multiple countries including the U.S., Canada and Germany.

This big idea started when multiple researchers, independently, came across algae blooms in cold-water samples and began talking about it with their colleagues. North first experienced this while taking samples from deep within an ice-covered lake in Canada.

“I pulled it up from under the ice, and it was full of algae,” she said of the sample. “It was quite a surprise, but the more we started talking about it, the more people had stories of their own of algae under ice.”

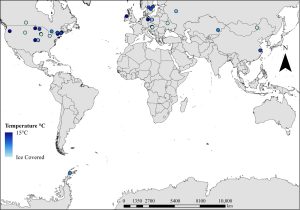

The international collaboration also allowed researchers to take water samples and look for cold water blooms across the globe where many other conditions may be present, which helped to rule out geographic abnormalities as a cause for the blooms in cooler temperatures.

North, who was the third author on the paper, contributed two sets of data to the study – one collected at Stephens Lake and the other at Bethel Lake, and she had a lot of help along the way.

At Stephens Lake, samples were collected by Emily Kinzinger, one of North’s advisees. Kinzinger graduated with her Master of Science in Water Resources, and used the data for her thesis, which, ultimately also contributed to the paper. In examining her data, Kinzinger noticed that cyanotoxin levels were highest at 15 degrees Celsius (or 59 degrees Fahrenheit), and this became the cutoff temperature for the paper North collaborated on.

At Bethel Lake, samples were collected by Rock Bridge High School students under the tutelage of their teacher, Greg Kirchoffer, and another of North’s advisees, Zohreh Mazaheri Kouhanestani, who is pursuing a PhD in Water Resources.

“It’s really kind of cool that these kids out at Rock Bridge get to have their samples included in the international study,” North said. “You look at the tables, and Bethel Lake is right there.”

Ultimately, when examining samples taken across many countries, the data supported North and her colleagues’ suspicions that algae blooms do in fact also occur in cold water.

According to North, the implications of this could have major impacts on agriculture and practices surrounding drinking water testing, which she says is traditionally only done in the warmest months of the year.

If drinking water is found to have cyanotoxins – the toxins created by cyanobacterial algae blooms – it presents a particularly troubling problem for communities because boil orders are ineffective and can even make matters worse.

“When you have toxin-producing cyanobacterial cells in the water, boiling bursts cells and actually increases the toxins,” North said. North hopes that the study will bring awareness to the potential for algae blooms that cause these toxins in the colder months as well as increased testing during these times. In addition to drinking water for people, she said there are agricultural implications as well, as livestock can be poisoned by these toxins if they drink out of a pond experiencing a bloom.

“You shouldn’t make assumptions about what’s going on in your pond based on the temperatures,” she said.

North has big plans to continue exploring the conditions for cold-weather algae blooms. This summer she will take a research leave to spend time in Germany at the Lebiniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology. There, she will work with an international team of researchers who will use several mesocosms — or “mini lakes” — where other conditions can be more closely controlled than in field settings.