Patients entering the parking garage of MU’s Hospital and Clinics pass something unexpected – corn and forage growing from a little plot of land. The crops aren’t a mistake, but a continuous experiment in soil erosion now a century old.

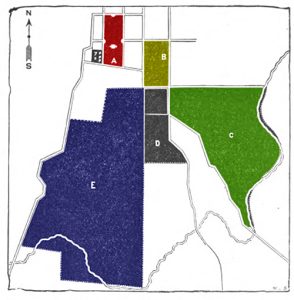

The quarter-acre island of agriculture in the sea of an urban medical campus is all that remains of the MU Horticulture Farm, part of the original endowment that helped establish the Missouri College of Agriculture. As MU expanded over the decades, the campus moved further into this property with buildings and other uses. Today, much of Mizzou’s academic campus, several residence halls, MU Health Care and Mizzou Athletics occupy this land. Only the quarter-acre of corn, the Duley-Miller Erosion Plots, remains of the old Horticulture Farm.

Building the College Farms

The Horticulture Farm originated with $90,000 in bonds issued in 1870 as part of the deal to bring the College of Agriculture to Columbia. A number of properties were considered by the Board of Curators – one was the Hudson cattle and dairy farm located southeast of the 22-acre MU Francis Quadrangle. Another was the Garth estate, southwest of the present day Columbia Public Library. Still another was the Rollins tract south of the Quad. This property was owned by James Rollins, father of Mizzou, and who brought the College of Agriculture to Columbia.

The Hudson and Rollins properties were chosen by the curators. With a vineyard donated by the College of Agriculture’s first dean, George Swallow, a total of 640 acres made up the College Farms.

The 640 acres were roughly divided into three areas. Hudson’s eastern section stretched from today’s College Ave. east to Hinkson Creek, and would be developed into the College’s beef, poultry and dairy section. Today, East Campus, as it is known, is home to the Animal Sciences Research Center, Eckles Hall, Connaway Hall and the MU College of Veterinary Medicine.

A second and smaller area east of the MU Quad to College Ave., Swallow’s old vineyards, was set aside for future buildings of the College of Agriculture. Today, these lands support Waters and Mumford halls, the Memorial Union, Gentry and Read halls, and the Agriculture Building.

The largest part of the land endowment, the Rollins tract, stretched from the Quad south into what is now Grindstone Park. This was named the Horticulture Farm.

While the animal and building tracts developed quickly for the College, the Horticulture Farm – with its rocks, stumps and brush – was ill suited for research and education.

In his book about the early history of the College, Frederick Mumford, the fifth dean, wrote: “It could have been developed, but tillable land suitable for cropping purposes was limited. [The] farm [had] sagging fences, buildings out of repair, weedy pastures, and a general appearance of neglect [that] was a liability rather than an asset. It was clear that considerable investment would be needed for the clearing of brush and timber, eliminating weeds from the pastures, and construction of adequate buildings. These funds were not available, and even if they had been this land was not well adapted to crop farming.”

Mumford, ever an innovator, saw the Horticulture Farm as the natural place for the University of Missouri to grow into – if better property was provided to the College in return. It would take Mumford 20 years to pull that horse trade together.

In 1931 he convinced the Missouri Legislature to fund a proper farm. This started with the 220-acre Beazley Farm, south of Columbia. Purchased at $65 an acre, the property was promptly utilized by the departments of field crops and soils. Three years later Mumford added the adjoining 442-acre Gauss Farm for $12,000. The curators later named these properties the University South Farms.

Groundbreaking Soil Experiments

The Horticulture Farm was put to use even as Mumford worked to replace it. Land that could be used for crops was cleared, with fruit trees covering the rest. A grazing pasture was established where the Hearnes Center now sits – the pasture’s Beef Barn still stands east of it.

The idea to start a runoff research project at the Horticulture Farm began in spring 1915. R.W. McClure, an undergraduate agriculture student, asked his professor, Merritt Finley Miller (1900-1965), about how much water would runoff after an intense rainstorm event.

Miller answered the question with a challenge. As told by C.M. “Woody” Woodruff, professor emeritus of soil science, to Randy Miles, current director of the Duley-Miller Erosion Plots, Miller had McClure design a “student problems” study to find out.

McClure placed wooden barrels at the downslope end of some plots away from the rest of the crops. After the first rainstorm, McClure asked Miller (who would later follow Mumford as dean) about what he should do with the sediments in the barrel as it interfered with the collection of water.

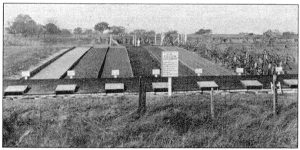

That got the MU soil scientists thinking about the relationship between rain, soil and crops. In 1917, Professor Frank Duley took McClure’s experiment and expanded it into seven 6 x 90-ft. test plots – the plots that exist today – to begin long-term tests. Duley used steel partitions to separate the plots to prevent runover from adjacent plots. Concrete basins at the lower ends of each plot collected runoff water and sediment. After each rainfall, the volume of runoff water was measured and drained, and the soil was removed, dried, examined and weighed. This was the first experiment in America to scientifically measure runoff and soil erosion.

This experiment lasted until 1940. Follow-on soil erosion research measured the ability of eroded plots to recover productivity and continued until 1985. This research found that the use of fibrous rooted plants with a well-balanced fertility program could restore lost soil productivity.

The MU soil experiments were used as evidence to support the establishment of the Federal Soil Erosion Service, now U.S. Soil Conservation Service. The MU plot design was adopted at 10 erosion stations nationwide. The collected data was used to develop the Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE), a widely used mathematical model that estimates soil loss under various practices and describes soil erosion processes.

A New Hospital Needs a Home

In the early 1950s it was recognized that MU’s hospital, the old Parker and Noyes halls on west campus, was inadequate for Columbia’s expanding population. $13.5 million was allocated by the Missouri Legislature to build a new University Hospital.

MU couldn’t go anywhere but south with the construction, and the Horticulture Farm looked like vacant ground to Jesse Hall. Because the College of Agriculture had gotten South Farms, there was no objection to the land transfer.

As buildings, parking garages and sidewalks went up, Duley and Miller’s plots were left in situ. They were too valuable in their continuing mission to provide long-term baseline data.

Over the years, the rest of the Horticulture Farm disappeared with construction of the VA Hospital, McHaney Hall, the Hearnes Center, a nurse dormitory and the new orthopedics hospital. Only the erosion experiment remained.

The significance of the little soil research station was recognized in 1965 when it was designated a National Historic Landmark. In 1988 it was named the Duley-Miller Erosion Plots in honor of their early research.