It was an unusually cool summer day in 1816 when the wagon of Thomas and James Hickman rolled to a stop on a grassy hilltop two miles north of the river town of Franklin. The brothers had left their home in Bourbon County, Kentucky, to come to the Territory of Missouri to build a new life.

They arrived in a wilderness, a horizon-to-horizon swath of tall-grass prairie and densely wooded creek bottoms. The Missouri, a tribe related to the Sioux, had been the area’s most recent inhabitants. By the time the Hickmans settled in, all but a remnant had been annihilated, victims of smallpox and warfare with the Sauk and Fox.

Two years after the Hickmans’ arrival, Thomas and his wife Sarah moved into a magnificent new home, which today is much as it was when completed. The 1819 Thomas Hickman House is a historic Missouri treasure located at the University of Missouri Horticulture and Agroforestry Research Center (HARC) in New Franklin.

The restored house, on the National Register of Historic Places since 2006, is a look at early 19th century pioneer living in Missouri.

A Little Old South in New Missouri

Thomas and James Hickman were looking for fertile soil, cheap land and business opportunities, much like the rest of the early settlers. If everything looked favorable, Thomas planned on building a house and moving his family to Missouri.

His plans fell into place in 1816 when Thomas joined in a partnership with fellow Kentuckian Benjamin Estill to buy a 40-acre parcel from David McClain – one of the first settlers to the Boonslick area. This land contained the site where the Hickman House now sits.

Thomas then joined with William Lamme in Franklin to form William Lamme & Co. to sell drygoods and supplies to pioneers moving west. Franklin by then was a booming river port second only to St. Louis. It would be the site where William Becknell started the Santa Fe Trail in 1821. Swept away many times by Missouri River floods, Franklin is virtually abandoned today.

Feeling he had a good start in this new country, Thomas built his new home. He then returned to Kentucky in 1818 and brought Sarah and their four children (two more would be born in Howard Co.) to Boonslick.

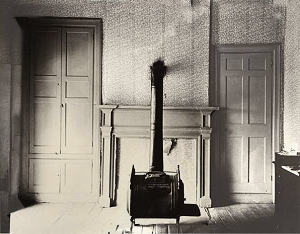

The approximately 1,400-square-foot story and a half house reflected the family’s prosperity. Designed in the Georgian-cottage style popular back in Kentucky, it featured a central hallway opening to a dining room and three bedrooms. A curved staircase provided grand access to the upper floor. A “summer kitchen” – a separate structure that kept cooking heat away from the main house – provided a place for a domestic slave, probably working alongside Sarah Hickman, to prepare meals.

In this house the Hickmans would raise their children. The house stayed in the family until the late 1800s when it was bought by Isham Crews. Remarkably, the house was never updated with modern plumbing or HVAC.

Lack of modern conveniences and age probably caused the house to be abandoned.

The Restoration

CAFNR acquired the home, and 540 acres that surrounded it, in 1953 to start a horticultural research farm. The center, now situated on more than 600 acres of scenic Missouri River Hills landscape, contains numerous varieties of fruit and nut trees. It conducts horticultural and agroforestry research.

By the Reagan Presidency, the Hickman House was one of the oldest brick homes in Missouri. Gene Garrett, then HARC superintendent and now professor of emeritus of forestry, began a campaign to raise funds to restore the house.

“The house was on the verge of deteriorating,” said Ray Glendening, HARC superintendent. “I could see signs that the house was declining faster: cracks in the exterior, cracks in the hallway walls, cracks that had opened up that weren’t there a few years earlier. The chimneys were missing a lot of bricks.”

Others noticed, too. Garrett began organizing community members and elected representatives. Sen. Christopher “Kit” Bond secured a $500,000 federal appropriation for the project. Additional money was secured including a $250,000 grant from the MU College of Food, Agriculture and Natural Resources, and a Missouri Department of Economic Development Community Development Block Grant. Funds from private donors included $100,000 from James Weathers, a Fayette resident who lived in the house as a teenager and whose mother kept a daily diary.

Period Materials and Period Construction Techniques

The $1.3 million project was no typical rehab. Modern building techniques and materials don’t always work on a house this old. Restoration experts were brought in to replicate as many of the original building techniques and materials as was possible.

The bricks, for instance, are not uniform in shape and color, and bear only a passing resemblance to their modern counterparts. Assembling a wall of them requires the skills of a stone mason, not a brick layer.

Much of the replacement brick and limestone foundation rock used was excavated from the ruins of a nearby home, called the Turner House, built just a few years after the Hickman House. “When it was all said and done we probably dug 10,000 or so bricks out of that house,” Glendening said.

The original mortar used to tie the bricks together was a lime-putty mixture, a material used before current Portland cement. Portland dries too hard for the old and soft bricks. A Chicago company was called in to mix the sand and lime mortar mixture. The bricks, by the way, are laid out in an intricate Flemish Bond design – too labor intensive today. Bricks and mortar weren’t the only old-school methods. Specialists in masonry and brickwork restoration had to remove the lime whitewash that once coated the house’s brick walls. They also repointed the exterior brickwork – a laborious process by which cracked and loose mortar is chiseled out of joints and replaced with new material.

AN ARCHITECT’S ANALYSIS OF THE RESTORATION

Other rehabilitation included constructing a new stone foundation. The four chimneys were rebuilt, the roof was re-shingled with period materials, and lead paint was removed and replaced with safe coverings. The original walnut and ash floors and woodwork were refinished, and broken interior plaster repaired. A summer kitchen was reconstructed based on archeological and historical information.

The windows were restored with new panes and sashes – a neighbor who saved window panes from a destroyed 19-century building donated them for historical accuracy.

Restoration was completed in 2009.

Furnishing a Home in 1819 Style

To give people of the 21st Century a glimpse into pioneer 19th Century Missouri life, the restored home was furnished in period style, and contains displays and artifacts of the area and the Hickman family.

A family related to the Hickmans loaned two portraits of the Hickman family. Others donated period furniture and clothing. Other items displayed – including buttons, coins and utensils – were found on-site during an MU archeological dig.

Bringing back authentic door and window placements were particularly important, explained Glendening. All of the house’s openings would have been designed to maximize the efficiency of fireplace heat in the winter and cooling breezes in summer.

Was the effort worth it? “We need to remember our past. That’s why we need to preserve this history,” Glendening said. “These are the people we came from. If you tear down these old houses and build new places, our understanding of what they did here, of how they lived, is lost forever.”