In 1874, a swarm of locusts collectively the size of California was eating their way across the American heartland, heading east. To a nation still wounded from the Civil War, it seemed like the end.

One person faced the swarm, determined to understand a way to control the pests.

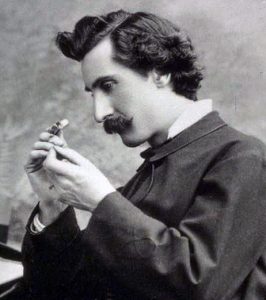

Charles Valentine Riley (1843-1895) was Missouri’s first state entomologist (and just the third in the nation) and the first professor of entomology at the new University of Missouri College of Agriculture and Practical Arts. Though he stayed in Missouri only nine years (1868-1877), he is credited with being the man who changed the way science studies bugs. His detailed written and sketched observations have been called the birth certificate of modern entomology.

In addition to his research to combat the locust, he introduced beetle predators to control populations of the cottony cushion scale insect that were destroying the California citrus industry. He is famous and revered in France for helping to save that nation’s wine industry.

The Life of Riley

Riley was born on Sept. 19, 1843 in London’s Chelsea district, the son of a Church of England minister. When he was 11, his parents sent him to Europe to further his science career. There he excelled at art and natural history, attending private schools in Dieppe, Paris and Bonn.

After the death of his father, he was brought home to Britain to enroll in a public school there. His mother remarried, which may have played a part in his decision, taken at the age of seventeen, to cross the Atlantic Ocean to America with scant resources.

Riley landed in Illinois, where he was employed as a laborer on a farm in Aroma, a small community 50 miles south of Chicago. Around 1864, he left the farm to work for the Chicago-based Prairie Farmer, a leading agricultural journal as reporter, artist and editor of the entomological department.

Riley’s journal observations were unique. His drawings were as much fine art as scientific renderings. His prose blended science, Victorian elegance and poetry. He quickly became the most famous bug expert in America.

That’s what Missouri – who had just established a research university and was about to found a college of agriculture – needed. Riley was appointed the first state entomologist of Missouri in 1868. Two years later, he joined the new College of Agriculture as a professor and lecturer.

Understanding the Locust Plague

As the locusts swarmed from the northwest, eating everything green in its path and laying eggs by the trillions in ravaged fields, Riley set to work to research the insect. He collected specimens from Canada in the north to Indian Territory in the south. He traveled to the fields of Kansas where impoverished farmers were still dazed by seeing their fertile crops disappear before their eyes.

Riley concluded that the swarm was a migratory species, the Rocky Mountain Locust (a species now thought extinct), whose breeding grounds stretched from Colorado into Canada.

Riley tackled the problem of the grasshopper systematically. He published guides to help farmers understand the pests they were dealing with. He detailed their feeding habits, how they gathered in swarms to travel long distances, their seasonable habits, how they laid their eggs, how they were affected by weather, what diseases plagued them, and how outbreaks developed. He wrote about predators of the insect and which pesticides did, and did not, kill them.

Riley’s fight with the locust created the best practices of the day – using poisoned bait with pesticides like liquid sodium arsenite and sawdust, improving plowing practices (plowing to at least five inches deep helped bury young grasshoppers emerging from the ground), improving seeding and tillage techniques, and using barrier strips, burning, catching machines, and planting immune crops.

Perhaps as important as these suggestions, Riley organized farmers and governments to report infestations and adopt his best practices.

Saving the French Wine Industry

In the late 1800’s, the French wine industry was being decimated by an insect, the grape phylloxera.

The crisis began with the accidental introduction of the insect (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae) from North America into the wine-producing districts of France around 1860. This wingless, aphid-like insect forms galls on the roots, stems or leaves of grapevines, and eventually kills the plants.

Within 25 years of its introduction, grape phylloxera had destroyed nearly one-third (25 million acres) of the French wine grapes and threatened to annihilate the entire industry within another ten years. Riley, who recognized that native American grapes (Vitis labrusca) were seldom injured by phylloxera, proposed grafting European vines (Vitis vinifera) onto American rootstocks. Riley’s reputation was so solid that even the French listened. In 1870, Riley began sending resistant rootstocks to J. E. Planchon in France who successfully grafted the French wine cultivars and grew them without injury in phylloxera-infested soil.

Thanks to Riley and Planchon, the French wine industry was saved from certain destruction and the commercial value of resistant plant genotypes was proven beyond a doubt. In appreciation for his services, the French grape growers gave C. V. Riley a gold medal. The French government awarded him its highest decoration, the Cross of the Legion of Honor. He was also named a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor in 1884.

One of Mizzou’s Earliest Scholars

Riley, who had no earned degrees, was an internationally recognized scholar in a state struggling to fund higher education in the post-Civil War depression. The University of Missouri awarded C. V. Riley an honorary PhD in 1873. As a scholar he was a prolific writer and artist, authoring more than 2,400 technical publications. He also published two journals, the American Entomologist (1868–1880) and Insect Life (1889–1894). In recognition of his work, he also received honorary degrees from Kansas State University, and was an honorary member of the Entomological Society of London. He is credited with founding the Entomological Society of Washington. He and L. O. Howard, Riley’s assistant in the Federal Entomological Service, were among the founders of the American Association of Economic Entomologists, which became part of Entomological Society of America in 1953.

The Death of Riley

In 1878, Riley left Missouri to become the United States Entomologist in the Department of Agriculture, an office which he occupied until 1894. In that year, he was appointed Curator of the National Museum and also became General Secretary of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

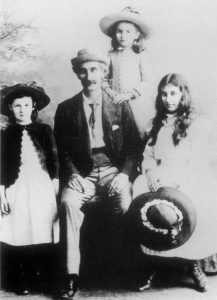

Just three days before his birthday in 1895, Riley suffered a bicycle accident that occurred not far from his Washington D. C. residence. He was riding rapidly down a hill, and the bicycle wheel struck a granite paving block dropped by a wagon. He catapulted to the pavement and fractured his skull. He was carried home and never regained consciousness. He died the same day at the age of 52, leaving his wife with six children. He is buried in Washington D.C.