Don’t look now, but your plants are glowing.

Research at the University of Missouri College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources is investigating this glow, or delayed fluorescence, that may someday help farmers monitor the health of their crops to more accurately apply fertilizers, water and pesticides.

“This research is very new,” said Jinglu Tan, director of food systems and biological engineering at CAFNR and one of the world’s few researchers in delayed fluorescence. “No, I can’t scan a field today with a camera and tell you what is wrong with them yet, but such technology is possible in the future.”

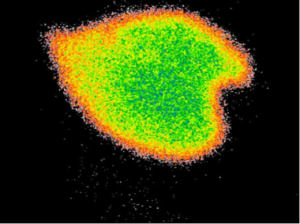

The glow is only visible now in darkness through an ultrasensitive camera. The emissions are caused by leakage of electrons from the sun’s energy captured in the plant during photosynthesis. The plant’s naturally occurring emissions are recorded by the camera and analyzed through advanced computer algorithms.

The glow patterns change according to the plant’s state of health and environmental stimuli. Tan’s research has shown that plants glow differently and uniquely during drought, or exposure to herbicides, and other chemicals. Tan said measuring this glow can tell scientists about changes in the plants health long before other observation methods.

In addition to using the glow to quantify the physiological status of plants, Tan is also hoping to use the plant’s glow as a biosensor to detect changes in the air or water. This research could be a new tool for monitoring the environment, said David Guo, a postdoctoral research associate who has been working on this research with Tan for eight years. Changes in the plant’s glow can show if there is an uptick in air pollution or increase in certain chemicals in groundwater.

The trick will be in learning how to more accurately interpret the glow. Guo and Tan hope to develop a portable instrument that can give a precise analysis of a plant from a scan of a leaf.