Today, men climb the stairs of Gentry Hall without a second thought. In the days when Corvettes had whitewalls and co-eds wore bobby socks, a man on the second floor of Gentry would have created screams. Between World War II and a 1972 renovation that converted Gentry to office and classroom space, the building was a women’s dormitory.

Gentry was built in response to a sharp increase in women attending college that continues today. In 1900, less than 3 percent of American women attended post-secondary schools. That number began to boom in the 1920s when Eleanor Roosevelt famously enrolled her daughter Anna in Cornell’s School of Agriculture. In 1939, more than one-third of MU’s student population was women (1,432 female to 4,144 male). Today, 52 percent of students attending MU are women.

An Addition to MU’s White Campus

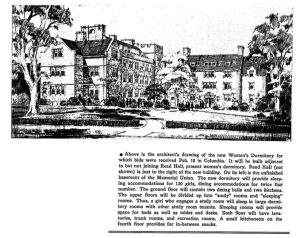

Construction of the limestone block Gentry Hall on MU’s “White Campus” started in 1939 on what was then the edge of campus. Jamieson & Spearl of St. Louis were the architects. This company was responsible for the design of most of MU’s buildings built between 1912 and 1950, including Memorial Union, Brewer Field House, Ellis Library and Faurot Field.

Gentry Hall’s opening was delayed by the military buildup preceding World War II. It opened in September 1942 and was immediately conscripted to house Naval aviators and mechanics being trained at MU (the first and last men to live there). In September 1944, it was turned back to MU and renamed the Women’s Residence Hall. It housed 160 students.

Today, most of Gentry Hall’s offices still have two closets, labeled A and B, used by the two students who shared each dorm room. As a women’s dormitory, there was no need for men’s restrooms – there is still no men’s restroom on the second floor. On the second floor there is a sound-proofed phone booth, its payphone long gone. The cubicle is now used for storage. Fireplaces in the reception rooms have been covered over. The fireplace mantels still exist, however.

Home Away From Home in the Forties

What was it like to dorm in what would become Gentry Hall? The Mizzou Alumnus Magazine in 1940 reported:

All rooms are equipped for two students. This includes individual closets, dressers, study tables, desk chairs, desk lights, two single beds, and a lounge chair. Each student is provided two warm woolen blankets, a pillow, linen for the bed, and a mattress pad. Furnishing bed clothing is a departure from usual dormitory practice. Rates for room and board are $26 per month or $100 per semester.

Curtains and matched bed coverings are also furnished. Extra bedding, desk blotters, a drinking glass, and a soap dish are provided in each room.

Care has been taken to make the Reception Hall in the Women’s Residence Hall as cheerful and home-like as possible. Each parlor has a large fireplace which adds to the effectiveness of the setting. The ground floor contains two dining rooms and two kitchens. On the upper floor is a kitchenette which makes serving at teas and receptions possible.

There is a recreational play room for the exclusive use of the residents. A Laundry is also provided.

The Residence Hall is managed by a director who is a trained dietician. The director plans all meals to furnish a well-balanced and interesting diet.

What the magazine didn’t mention is that the building wasn’t air conditioned until its 1972 renovation. The masonry building would get so hot in the summer months that students were forced to sleep on the building’s roof to escape the hot dorm rooms.

Dorm Life in the Soaring Sixties

Deb Batterson, an editorial assistant for CAFNR’s Office of Advancement, roomed in Gentry her freshman and sophomore years, 1962-64. “I wanted an assignment in one of the new dorms – Laws, Lathrop and Jones – but I got Gentry and cried because it was such an old building,” Batterson said. “I came to love it, mostly because of the people.”

Batterson’s first room was a “triple” – three beds, three desks, two large drawers for clothes and two small closets. “Students were not allowed to cook in their rooms, so when we popped popcorn or heated up cans of food in a pot that heated water, we stuffed towels under the door,” she said. “This was the first time, and I think the last, that I ever ate enchiladas out of a can. We played a lot of Canasta, and listened to Johnny Mathis records. That first year was the Cuban missile crisis. We were huddled around our transistor radios and thought about the boys we cared about going to war against Cuba and the Soviet Union. We were scared.”

The second year, Batterson was in a “quad” – four bunk beds. This room is the current DASS Division Director’s office. “We had windows on three sides, so we could wave goodbye to our dates when they drove down the alley,” she said.

Bad news came over the AM radio (television sets were rare at MU at the time) in 1963. “It was during that fall that President Kennedy was shot,” Batterson related. “The first bulletins we didn’t believe, but knew soon enough that it was true.”

Batterson said during those years the university was in loco parentis, which loosely translates to parents in place. “Curfews were strict,” she remembered. “The front doors were locked at 10 p.m. weeknights and midnight on Friday and Saturday. Occasionally we could get permission to stay out until 1 a.m. – I think we were allowed two times a semester. If you didn’t get inside that door before it was locked, you got ‘campused,’ which meant you were not allowed to leave the dorm the next Friday and Saturday nights. I got campused once – I couldn’t get my umbrella folded and through the really narrow door in time. During my detention, my roommate and I ate chocolate chip cookies from her mom, played records and sang Rock Island Line over and over. You would have thought it was a party!”

Men were not allowed upstairs. Visitors had to tell a receptionist the name of the person being visited. “The receptionist would buzz us when a guy wanted to see us and we went downstairs,” Batterson said. “When repairmen came on the floors they were supposed to loudly shout ‘man on floor.’ Most only muttered it, and you would come out of the restroom to find a guy working on the water fountain. You hoped you weren’t indecent.”

“The fourth floor was creepy at night,” Batterson said quietly. “The wind sort of moaned and whistled through the attic. There was a crawlspace door up there about which bad and scary stories were told. We studied up there, but when you were the last one left, you scurried downstairs afraid to look back!”

Named for Sarah Gentry

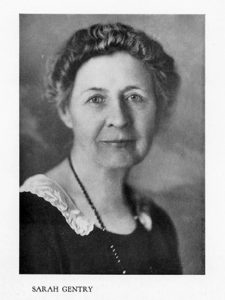

The name of the MU Women’s Residence Hall was changed on Oct. 4, 1952, to Gentry Hall to honor Sarah Gentry, a prominent Kansas City educator and the second female graduate of MU.

Gentry was born in 1855 in Audrain County, the granddaughter of General William Gentry who commanded the Union’s Fifth Provisional Regiment Missouri Enrolled Militia during the Civil War. After the conflict, the family moved to Columbia where she attended the university. She received two degrees, a bachelor of science in 1873 and a master of science in 1876.

She moved to Kansas City to teach at Central High School. In 1877 she married Dr. John Elston, one of the founders of the University Medical College of Kansas City.

After Dr. Elston’s death, Gentry taught in Kansas City’s Woodland School for two years, beginning in 1894. Then she became a teacher of English and American Literature in the Manual High School. She stayed in this position until her retirement in 1915.

Gentry died Jan. 17, 1944, at the home of her daughter, Mrs. Donald Witten, in Washington, D.C. Another daughter, Bertha, also a Kansas City teacher, preceded her in death. The Sarah and Bertha Elston Scholarship for High School Girls was established by Kansas City area high school teachers and Gentry’s son, Allen Elston.