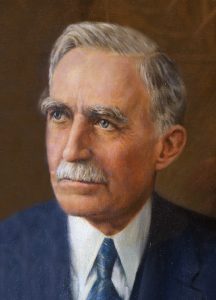

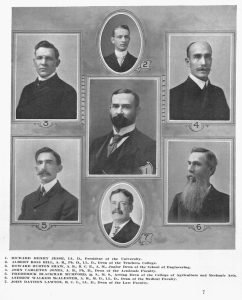

When Frederick Blackmar Mumford (1868-1946) became the fifth Dean of the Missouri College of Agriculture in 1909, he faced an entirely different situation than his predecessors did.

The first two Deans, George Swallow and J.W. Sanborn, struggled just to start an agricultural college within an underfunded liberal arts university. The second pair, Edward Porter and Henry Waters, forged relationships (painfully at times) with Missouri farmers to make the college responsive to their needs while establishing small but meaningful research and education programs.

The earlier Deans bequeathed Mumford a relatively solid organization with a lot of promise. Jesse Wrench, a Mizzou history professor from 1911 to 1953 and friend of Mumford’s, noted that while MU ag was developing into a foremost agricultural college, it was “still somewhat an orphan.”

Mumford decided to make the orphan a preeminent school.

This was a goal that Mumford is credited with accomplishing. Writing in the Journal of Animal Science in 1992, Richard Lee said agricultural writers and historians are unanimous in praising Munford’s leadership. “He transformed a struggling college into what is now a top ten institution,” Lee wrote. “His work had a profound and positive effect on agricultural education and research for three-quarters of a century. Truly significant developments in agricultural education and federal support are the result of Mumford’s foresight, work habits and leadership while he was Dean of the College of Agriculture.

“Mumford frequently noted that he considered himself fortunate to have lived at a time when so much progress in scientific agriculture was being made. But few believe that all of this progress would have been made with anyone else in charge.”

Today, the Mizzou College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources honors its best and brightest each year with the annual Frederick Blackmar Mumford awards.

The Brothers Mumford

Frederick Blackmar Mumford was born on a farm near Moscow, Mich., May 28, 1868, to Elisha Charles Mumford and Julia Ann (Camburn) Mumford. Frederick had one sibling, a younger brother named Herbert Windsor. Their early education was in a one-room schoolhouse.

Frederick and Herbert both showed an interest in agricultural science. Despite their mother’s worry of the corrupting worldliness of a college and their father’s skepticism of the value of an agricultural education, both entered Michigan’s Albion College where they stayed three years. The brothers then transferred to Michigan Agricultural College (now Michigan State University) where they earned bachelor of science degrees in 1891. Two years later they received their master of science diplomas.

Herbert later became Dean of the Illinois College of Agriculture, now the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, while brother Frederick was Dean of Missouri’s school. As Kansas State University and the University of Missouri both have a Waters Hall to honor Henry Waters, who served both institutions, MU and the University of Illinois both have Mumford Halls, albeit for their respective deans. MU named Mumford Hall when Frederick was still alive – an unusual honor in academia.

Frederick taught at MAC for two years before being recruited in 1895 by Henry Waters, fourth Dean of the Missouri College of Agriculture. Waters dreamed of a world-class corps of agricultural educators/scientists who would transform the struggling school into a research and teaching power. He aggressively sought out the best and brightest in their fields. Mumford met that qualification.

Wrench thought Mumford took a leap of faith by coming to MU. Mumford, already recognized for his animal science research and books, was being heavily recruited by numerous agricultural schools without MU’s contentious history and stingy salaries.

Mumford quickly achieved tenure and became head of MU’s Animal Husbandry division, a program he grew into an important research and education division from just nine animals. He also wrote a string of textbooks on modern farming, some still used as standard texts years after his death. He traveled to Europe to give a series of lectures on animal science techniques – boosting the reputation of his struggling college.

A Reluctant Dean

When Waters resigned to become President of Kansas State University in 1909, Mumford was immediately appointed as Agriculture Dean.

Writing about himself in his 1944 book The History of the Missouri College of Agriculture, Munford said he accepted the position with hesitation and reservation. While there had been real improvement during Waters’ administration, the College still suffered by comparison with other colleges. Mumford shared Waters’ vision of making Missouri an internationally recognized school. He developed a plan to achieve this.

“Clearly, the Missouri College of Agriculture could not boast of excellent buildings, land, livestock or laboratory equipment in 1909,” he wrote. “But it did have an exceptionally well-trained, far-visioned and industrious faculty, and the essentials of a thoroughly good course of instruction. By limiting the number of research projects, we could insure that individual projects would be as well financed as in larger institutions. It was therefore not strange that great emphasis was placed on quality work, quality teaching, quality research, and economy and efficiency in every department. This policy resulted in graduating men with the confident assurance that they were well trained. It gave to the institution a reputation for economical administration and the maximum of accomplishment with the funds available. The degree of Bachelor of Science in Agriculture from the Missouri College of Agriculture became ‘legal tender’ all over the world.”

It was this small corps of exceptional faculty members, begun by Waters, which Mumford would build upon to earn a national reputation for his Missouri College of Agriculture.

The Elite 26

Mumford’s faculty were soon nicknamed the Elite 26.

These 26 formed many of CAFNR programs of today. Under Mumford’s leadership, they established the departments of forestry, farm management, poultry husbandry, soils, field crops and dairy husbandry. New buildings for veterinary science, agricultural chemistry, administration and the hog cholera serum plant were built. Members of the 26 included names still familiar in the agriculture community – Samuel Brody, J.W. Burch, J.W. Connaway, A.J. Durant, Albert G. Hogan, Harry Kempster, A.C. Ragsdale, W.H.E. Reid, E.A. Trowbridge, C.W. Turner and L.A. Weaver.

These faculty stayed with MU through their entire professional careers, noted John Longwell, an Elite 26 member himself, noted animal scientist, later Mizzou Ag College Dean, and President of North Dakota State University. “The Elite 26 established research and teaching programs that resulted in statewide recognition of the College by the agricultural industry. Each made a unique and valuable contribution to the development of the College,” Longwell wrote. “Their long service gave continuity to College programs.”

Longwell wrote that it was a miracle that the 26 stayed at MU: “Missouri’s salaries were considerably below that at many other agricultural colleges and many men were invited to move with increased salaries and higher operating budgets. Each of the men chose to remain at Missouri for reasons of his own, but a major reason probably was the freedom and encouragement which Mumford extended to them to pursue the research and teaching program of each person’s choice.”

Longwell added that Mumford, a modest man, was quick to note the contributions of others. Mumford’s support for a good idea was absolute and doggedly provided resources for anything significant that a faculty member wanted to try.

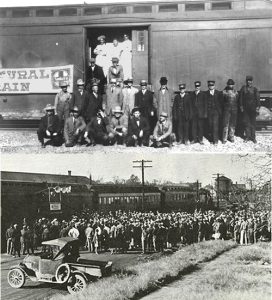

Railroading Education into the Counties

Mumford realized that to really reach Missouri farmers who were too busy to come to Columbia for short courses, the College had to do something unique. In 1912, Mumford leased special trains that stopped in all 42 Missouri counties where the railroad had tracks. “Five men from the College in thirteen days’ time gave instruction to 93,800 people from special trains,” Mumford proudly reported. “On these trips, 98 stops were made and 512 lectures on agricultural subjects were made by men from the Missouri College of Agriculture.”

Education Beyond a Four-Year Degree Program

Mumford also encouraged farmers to take advantage of the faculty’s scientific knowledge. While Mumford’s trains rolled across the state, the College received and answered 63,680 letters from farmers looking to improve production – an increase of 21.5 percent over the preceding year. The next year, College faculty answered a total of 109,557 questions from Missouri farmers.

With Mumford supplying some pressure, the old but disreputable concept of the county agent was modernized and made relevant. Previously, county agents were small town political hacks with no special science knowledge. Few farmers listened to them.

In 1914, Mumford and A.J. Meyer, secretary of the Agricultural and Home Economics Extension Service, developed a rigorous training program for a new corps of county agents who could not only recommend science-based production techniques, but could liaison with experts at the College to tackle farmers’ problems. These new agents not only talked seeds and planting, but could provide sound economic advice, too.

Old ways die hard and Mumford had to engage in some personal selling of the idea. One grizzled farmer announced that he was opposed to the idea and loudly complained to the Dean. “He had developed a fine 600-acre farm without any advice from a young whipper snapper of a college boy and he believed he knew more about his own farm than anyone from the College,” Mumford wrote. “When, however, I asked him if all the farmers of his county were equally efficient, he agreed that they were not. He admitted that it would be a fine thing for his county if every farmer could get expert help to be as efficient and successful as he had been.”

Mumford also helped organize the first correspondence courses in agriculture. Though he caught flak from other educators, he made sure that college credit could be earned at the course’s completion. Other colleges of agriculture followed Mumford’s lead.

Mumford inaugurated the first five-day short courses to be given outside of Columbia. The instruction was to be concise, practical and adapted to each region, he said. Two teachers were assigned to the task of conducting the course and giving the lectures and demonstrations. More than 100 applications were received in the first month of these courses.

In his book, Mumford proudly noted the improving reputation of the College: “Some evidence of the increasing stature of the College is to be seen in its selection as the sponsoring institution for the international Graduate School of Agriculture in the summer of 1914. Many of the leading teachers and scientists of the United States and foreign countries joined with the faculty of the MU College of Agriculture in lectures and demonstrations showing the great advance of agricultural science throughout the world. One principal theme was devoted to the new science of genetics. This conference of leaders in agricultural education and research was a great inspiration to our faculty. One tangible result was the appointment of Dr. Darbyshire of England as professor of genetics in the Missouri College of Agriculture.”

It was in 1914 that Mumford signed-off on a ground-breaking four-year curriculum offered to women who desired training in agriculture or home economics. Even conservative newspapers of the day supported the idea because Mumford was behind it. Twenty years later, Eleanor Roosevelt famously enrolled her daughter into the Cornell School of Agriculture as a way to blaze a trail for women in the practical sciences.

Mumford the Unsmiling Leader

In the 1992 biography published in the Journal of Animal Science, Lee said Mumford’s acquaintances described him as aloof, formal, restrained, dignified, reserved and even cold. Very few glimpsed him, even in the hottest summer weather, without a coat and tie. Seeing a smile was cause for the news to spread across campus.

Lee’s older brother, an ag student in the 1930s, said few were surprised at Mumford’s formality while introducing the visiting Dean of the Illinois College of Agriculture who was speaking on the MU campus. Mumford simply said it was a pleasure to introduce Herbert W. Mumford. Frederick made no mention was made that the two men were brothers.

Mumford employed Lee as a research assistant for Mumford’s History of the Missouri College of Agriculture. Summoned to report one hot summer afternoon, Lee found the Dean at his desk in shirt sleeves and his feet propped up on a desk drawer. “What a surprise,” Lee exclaimed.

Mumford’s leadership style was simple, Lee said. Mumford would tell the faculty member that he was the best suited to accomplish a task and was given an assignment. The faculty member was told to report back when the job was complete. If additional resources were needed, the magic words that cleared all objections were: “Mumford wants it.”

Mumford may have been stern, but he was respected with a reputation of getting hard things done. Both the Governor and President appointed him to positions of importance during World War I. He was director of the Missouri Council of Defense and administrator of the Missouri Division of the U.S. Food Administration. As head of these defense organizations he was responsible for the conservation of resources, coordination with state and federal agencies, and the prevention of black market speculation. His efforts increased food production. In 1919, he was named a member of the Mission Americaine de Rapproachment, a Presidential project to judge France’s need for economic assistance after the war.

In the Roaring Twenties, Mumford was asked to chair federal committees to find ways to boost agricultural yields. In 1925, Mumford wrote two bills, passed by Congress, that increased animal science research funding to Land Grant Colleges. In appreciation, the Sirloin Club of Chicago hung his portrait in a place of honor.

During the Depression, Mumford served on the Missouri State Board of Agriculture, Missouri Relief and Reconstruction Commission, Farm Debt Adjustment Committee, and State Planning Board. Mumford retired in 1938 after serving the College of Agriculture for 43 years.

After retirement, Mumford continued his activities to benefit the College. He remained active at Mizzou and worked as President of the Association of Land Grant Colleges and Universities. Through this association, Mumford improved agricultural education by using land grant institutions to influence national and state legislation.

A Fatal Need for Speed

Mumford had a reputation as a hot-footed driver. M.F. Miller, one of the Elite 26, said he would never forget his first wild ride with the Dean. “Mumford was driving his new Chandler car…I feared I would never see Columbia again.”

Miller described Mumford’s last drive: “The Dean’s fast driving ultimately caught up with him when his car crashed into a bridge abutment over a small stream five miles east of Wentzville on U.S. Highway 40.” According to the Missouri Highway Patrol, Dr. and Mrs. Mumford were driving from Columbia to St. Louis to board a plane for Florida. The car traveled a great distance along the road’s shoulder before hitting the abutment, overturning and catching on fire. There were no witnesses to the accident, but passers-by pulled the Mumfords from the car. Mrs. Mumford died 90 minutes after arriving at the hospital in St. Charles.

On November 12, 1946, in St. Charles, Mumford died from injuries he received the month before. He was 78. Frederick’s brother Herbert had died in his own automobile crash in 1938.

Mumford’s Legacy

When Mumford arrived in Missouri in 1895, the College of Agriculture’s library had just four books. When he left in 1938, the library boasted 25,000 volumes – ranking it among the largest in the nation. During that time the faculty grew from nine full-time members to 75. There were 900 enrolled students in 1938 – making MU one of the biggest ag schools in America.

In his tribute to Dean Mumford upon his retirement, Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace noted that 99 percent of the College’s graduates had completed their studies while Mumford was Dean. Wallace, who 10 years later would unsuccessfully run against Harry Truman for President, said it would be difficult to calculate the immense impact that Missouri’s graduates were having on commercial agriculture around the world.

Cordell Tindall, long-time editor of the Missouri Ruralist magazine, noted in 1984 that it was Dean Mumford who gained acceptance for scientific agriculture. “Credit for building the Missouri College of Agriculture into the major institution that it is today largely goes to Dean Mumford. He not only proved to be a capable administrator, he had the perception to attract qualified faculty and department heads. Dean Mumford left his successors a heritage of respect for the Missouri College of Agriculture.”

Iowa State College President Hughes quoted an official of the U.S. Department of Agriculture as saying, “Under Mumford, the University of Missouri Experiment Station accomplished more per dollar spent than any other.”

W.C. Etheridge, who handled the College’s department of field crops during Mumford’s tenure, noted how College-developed crops became state’s standards, boosting yields and bolstering the economy. These included Missouri Early Premium wheat, Missouri Nos. 8 and 47 corn, and a variety of oats named for Columbia that quickly accounted for 80 percent of all production in Missouri.

Etheridge pointed out how Mumford and his faculty started Missouri’s soybean industry – going from nothing to 700,000 acres planted during Mumford’s tenure. Today, soybeans are Missouri’s most important single crop.

Frederick Blackmar Mumford is buried under a simple headstone in Columbia Cemetary, not far from the graves of George Swallow, Edward Porter and Henry Waters.