It began 40 years ago with what could best be called a “grand experiment.” For decades, faculty at the University of Missouri’s Department of Biochemistry had one collective goal — to study life at the molecular level — but were in two separate units, one housed in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources under the name agricultural chemistry and one in the School of Medicine under its current name.

It is about a 15-minute walk from Schweitzer Hall, located on the northeast corner of campus, to the medical school. The first merged department chair, Jim Gaylor, had the cross-campus walk down to a science; with the long strides of his 6-foot-4 inch frame, it took him approximately 1,700 steps. Until the agreement to have a joint affiliation with a singular unit of Biochemistry, with some exceptions (such as sharing a graduate program), the two units were running mostly on their own accord.

“There has been great support from both sides, and the experiment that started 40 years ago has borne fruit in the creation of other academic units that are jointly affiliated with more than one school or college,” says Jerry Hazelbauer, Curators Distinguished Professor of Biochemistry who has served as the department’s chair since 2000 — the same year the bioengineering department was created as a jointly affiliated unit between CAFNR and the College of Engineering.

“Just like one individual can’t know everything or have all the right experience or insights, neither medicine nor agriculture can provide all of the insights one needs,” Hazelbauer adds. “Working together and combining those efforts and expertise is by far the best way to make progress, and it’s something that’s strongly practiced throughout this campus. We’re proud to be the real pioneer in doing that.”

The partnership works, Hazelbauer adds, because the deans in both CAFNR and the School of Medicine have shared the same goals for scholarship, research and teaching. Importantly for a jointly affiliated unit serving the greater good, the expectation of both deans have been that MU Biochemistry as a whole fulfills its respective obligations to the School of Medicine and CAFNR — not that one group of faculty serve only one or the other.

“We simply have to pull our own weight and that combination has been extremely productive for us,” he adds.

This Friday, the MU Biochemistry community will be celebrating that partnership during its event, “40 Years of Biochemistry: Bridging Boundaries for the Greater Good,” taking place at the Bond Life Sciences Center. The event will also serve as pre-birthday party for Boyd O’Dell, a professor emeritus who will be celebrating his 100th birthday on Oct. 14.

Still, in order to appreciate where the program has been and is headed, we must take a look at its origins.

Rooted in agriculture

The agricultural side of the story begins with Joseph Granville Norwood who taught agricultural chemistry from 1858 to 1872. It was taught in Academic Hall (whose six remaining columns from a fire in 1892 have become a cherished symbol for all of MU) from 1860 to 1887. German chemistry professor Paul Schweitzer (the namesake of Schweitzer Hall) arrived at MU in 1872 — two years after the founding of what would turn into CAFNR — to replace Norwood.

In 1885, Schweitzer began teaching agricultural chemistry as a “half study,” before it became an official (and the first) department in the College of Agriculture in 1894, with Schweitzer giving three lectures a week. He served as chair of the department from 1894 to 1907, when he resigned. At the time, he was the longest-serving college professor in the state, according to the History of the Missouri College of Agriculture.

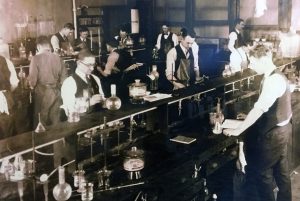

When the Agricultural Experiment Station was established by the MU Board of Curators in 1888, Schweitzer initially served as its director before being replaced by J.W. Sanborn later that year. In the early 1900s, the station began a program that involved feeding and analyzing livestock. That practice, and the entire Department of Agricultural Chemistry, would eventually move to the basement of Schweitzer Hall, which was built in 1912.

O’Dell is the oldest living member of MU Biochemistry, having first stepped foot on the MU campus in 1937. After having completed several credit hours at what is now known as the University of Central Missouri, he transferred to Columbia and earned a chemistry degree from MU in 1939. He stayed at MU to pursue a master’s and doctoral degrees in agricultural chemistry under the leadership of Albert G. Hogan.

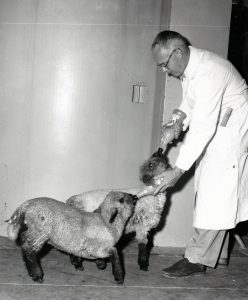

Hogan came to MU in 1920 as a professor of nutrition in the Department of Animal Husbandry (now known as the Division of Animal Sciences). When Hogan became the chair of the Department of Agricultural Chemistry 1923, the department began to switch from an analytical focus to a nutrition-focused effort that would put MU at the forefront of vitamin and trace-mineral-deficiency research.

Hogan, who received three degrees from MU, was mentored during his doctoral studies by “the father of American nutrition,” biochemistry professor Lafayette Mendel at Yale University. Hogan later discovered folic acid in 1939, an important nutrient for women during pregnancy, and its role in supporting healthy brain development in infants. In 1949, Hogan’s research on nutrition and congenital malformations led to the first grant from the National Institute of Health at MU. O’Dell has earned international acclaim as well, most notably for his pioneering research on how phytic acid interferes with the absorption and use of zinc.

“He (Hogan) was not a blustery or self-acclaiming person, but he was very persistent and wanted to do experiments many times to be sure that he was right,” O’Dell says of his mentor, whose research surrounding the vitamin B complex involved work with pigs, poultry, rats, guinea pigs, hamsters and pigeons.

Starting up at Schweitzer

When O’Dell became an assistant professor in 1946, his laboratory was housed in the basement of Schweitzer Hall, where he conducted his research on trace minerals in chickens, rats, mice and guinea pigs. O’Dell kept all of the animal and feed downstairs. At one point, Richard Bloomfield, who served as chair from 1967-69, had a “rat maze” on the same floor for nutritional studies, says Doug Randall, professor emeritus of Biochemistry.

The animals and their feed mixed with the odor from the previous work on animal carcasses in the old sub-basement and the hydrogen sulfide from the chemists on the second floor made for a less-than-ideal working environment before the building underwent a six-year renovation beginning in 1979.

“This was a very primitive place,” Randall says. “But Boyd never voiced a complaint, even though his facilities were really, really primitive.”

O’Dell agrees.

“We didn’t let little things like dirt stop us from doing some research.”

Then there were the cockroaches.

“You’d come in at night and turn on the lights and the floor kind of crawled away,” says Randall, who began conducting his plant-based research in Bloomfield’s old lab space in 1972 following Bloomfield’s death. “They were in the walls. They were just part of the system. It was just one of those things.”

And don’t forget about the brown recluse spiders that lived in the attic. Dick Campbell, who served as chair of the medical school unit of Biochemistry and later as the interim chair of the merged department from 1973-1977, conducted research on brown recluse spiders to attempt to find an anti-toxin. His technician, Joe Forrester, could go in the attic and retrieve 20-40 specimens after just a half hour.

Randall says the ratio of cockroaches to spiders was about 50/50.

“I don’t know if they met in the middle or not. We might have had some interesting creatures, especially considering the low-level of radiation present in the building prior to renovation,” Randall says.

A radiation scare in 1979, coupled with the national hysteria caused by the Three Mile Island partial nuclear meltdown in March of that year, created a need for the renovation of Schweitzer Hall. Additionally, a new professor studying photosynthetic bacteria, Judy Wall, and her research associate Barbara Giles, both were pregnant, raising the concern of radiation exposure in the building.

In the 1920s and ’30s, chemistry researchers produced radium from pitchblende (a mineral black in color that is composed mostly of uranium oxides), which contaminated the building with low-level radiation. Wall, who is now a Curators Distinguished Professor of Biochemistry, said one simply had to walk around with a Geiger counter, which detects radioactive emissions, to know exactly about people’s patterns of behavior based on hot spots.

“You could sort of tell where people were and what they were doing,” Wall says.

Lloyd Thomas, a former chemistry professor, was one those radium researchers.

“You could go through the journals in the library and find the ones that Lloyd used a lot,” Randall adds.

In the end, no more than 76 microcuries of radioactivity were found in the building, Randall says. The building finally received the renovation it needed as faculty moved temporarily to the Chemistry Building or had other arrangements made.

On the other side of campus

In 1872, the MU established the School of Medicine and named Norwood its first dean. Although Schweitzer began teaching a physiological chemistry course during the school’s first year, the school did not offer its first course in biological chemistry until 1907. In 1921, the Department of Physiological Chemistry formed with Addison Gulick, serving as its first chair and professor. Among those who Gulick taught were Frederick Robbins, who won the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1954, and Boyd O’Dell. 1953, it changed its name was changed to the Department of Biochemistry.

“This name was warranted to indicate the modern direction we would take,” Thomas Luckey wrote in a memoir in 1991.

Luckey became professor and department chair of Biochemistry at the School of Medicine in 1954. Dr. Roscoe Pullen, then the dean of the medical school, recruited Luckey from a faculty post at the University of Notre Dame.

“I left Notre Dame for greater academic freedom,” Luckey wrote. “Academic freedom was the strength of [MU].”

The School of Medicine had begun a four-year Doctor of Medicine program after offering a two-year bachelor’s degree program for nearly 50 years.

In 1954, medical students asked Luckey and a faculty colleague to sponsor a medical fraternity that would accept blacks and women. The only medical fraternity on campus prohibited membership for both groups. Luckey wrote that 19 of the 35 students in the first (four-year) class signed a petition for a fraternity without membership restrictions. With Luckey’s help, a Phi Chi medical fraternity chapter was formed with an associated group accepting blacks and females. Luckey notes “rapport with these students was very good.”

McAlester Hall housed the newly formed Department of Biochemistry, and a small annex north of the building served as a space devoted to animal research. The building was renamed from its former title of the Medical Laboratory Building in 1923 after Andrew W. McAlester, who succeeded Norwood as dean of the School of Medicine in 1880 and served in that role until 1909. The school’s clinical departments lived in the neighboring Parker Hall — formerly Parker Memorial Hospital.

When the department began, Luckey had a healthy budget for student equipment. The students were “well equipped” with access to several ground glass apparatuses, new balances and a dozen colorimeters, he wrote.

In addition to Luckey, Owen Koeppe and Arnold White joined the faculty. Both began as assistant professors. John Franz served as an instructor.

“We divided chores and provided good service,” Luckey wrote.

Among the first four faculty members, several specialties emerged. Luckey concentrated on general biochemistry with an emphasis in vitamins and nutrition. Koeppe studied proteins and enzymes, while White studied carbohydrate metabolism and clinical biochemistry. Franz studied hormones and lipids.

The faculty members designed the original biochemistry course to help students establish a strong background in biochemistry with an emphasis in biochemical processes at a molecular level. The students enrolled in the course often came from various backgrounds, so the biochemistry course also covered concepts from organic, qualitative and quantitative chemistry. Medical students constituted the majority of the class, although graduate students also enrolled.

Medical students could participate in summer biochemistry fellowship programs sponsored by funding agencies. The department also offered self-directed biochemistry electives during for fourth-year students. Luckey wrote later that he had repeatedly requested that biochemistry be a requirement for entry into medical school and that the course be upgraded for advanced students. However, this biochemistry course continued to enroll both beginning and advanced students.

A full accreditation survey by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) conducted in 1957 reported: “Dr. Luckey has with him an alert, young and capable staff. They have considerable enthusiasm, both for teaching and investigation. This department should develop into one of the strong contributing departments within the school.”

Janice Franz remembers the early days of the department when her husband, John, began as a faculty member.

“We were all young together — had kids the same age,” Mrs. Franz said of the faculty members and their families.

She recalls department picnics, softball games and traveling with her husband to attend conferences.

“Everyone knew everybody else,” she said of the friendly atmosphere among those in the department.

Mrs. Franz raised four children with her husband and returned to work in a lab at MU in 1973 while pursuing a master’s degree in biochemistry. She received a degree in 1975 and worked for 16 years as a lab member for several MU Biochemistry faculty members before she retired in 1989.

All of the Franz children attended Mizzou, and one of their daughters, Kathleen Quinn, now serves as the associate dean for rural health at the School of Medicine.

Coordination between schools

Luckey noted “profitable relationships” between the Department of Biochemistry in the School of Medicine and the Department of Agricultural Chemistry in the College of Agriculture. After all, both entities spent the first 30 years of their existence sharing the same facilities and faculty.

Luckey served on an ad-hoc committee in 1958 with Charles Gehrke, a professor in Agricultural Chemistry at the time, to help the university obtain research equipment. In 1959, the committee successfully requested and received an electron microscope from the National Science Foundation. The same year, the department hosted the first West Central States Biochemistry Conference on campus. The gathering brought together biochemists from throughout the Midwest.

In 1964, the Department of Agricultural Chemistry started a series of lectures that later became Nutrition Emphasis Week. Luckey was co-founder of the Graduate Nutrition Area degree program, along with cooperation among faculty members from other departments.

Gehrke and Luckey also had ties to NASA. Luckey served as a nutrition consultant to NASA for Apollo flights 11-17. In 1969, the U.S. government asked Gehrke to examine rocks that were brought back from the moon by the Apollo 11 Mission, during which Neil Armstrong became the first person to step on the moon’s surface.

Gehrke, who had co-founded ABC Laboratories in 1968, was asked to study the rocks because of his groundbreaking work on amino acids. The chromatograph he used to look at lunar samples is now part of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

Later, Benedict Campbell and Robert Wixom joined the faculty. Koeppe succeeded Luckey as chair in 1968 and served until 1973. 1974, Wixom made news when he became the test subject for his own experiment on long-term intravenous (IV) feedings. All of his nutrients were supplied by IV feedings for 48 days.

“Since [Koeppe] was so well liked, this was done with a minimum of problems,” Luckey wrote about his decision to resign as department chair. “He would have been wooed elsewhere if we had not done this. One of his first actions was to change the early morning lectures to mid-morning!”

Koeppe became MU’s provost in 1973, when Campbell became interim of chair of MU Biochemistry. It was during Campbell’s leadership, in 1974 that the two units began to pursue a shared focus on molecular biology.

A time of change

Sometime in the ’70s, after it was determined that the merger would happen, two associate deans from the College of Agriculture and the School of Medicine and the department chair of both biochemistry units visited Michigan State University to observe its biochemistry program, which served four of its colleges, including its agricultural and medical colleges.

“That was unique and was one of the reasons we wanted to explore it,” O’Dell says.

Leading up to that point, though, were a series of joint departmental discussions between CAFNR and the School of Medicine, as the two different cultures tried to figure out how to co-exist and become one.

“I think one important thing is, prior to the formal merger of the departments or once we decided it would happen, the discussions were long,” says Randall. “They were intense and sometimes heated, but because of that, when it was done, there was no doubt we weren’t going back. We were not separating.”

When Randall first arrived on campus in January of 1972, he was the first hire in the area of plant biochemistry. O’Dell, who chaired the Department of Agricultural Chemistry from 1971-72, made the hire along with Warren Zahler, who was filling in the reproductive biochemistry role that Dennis Mayer had left after serving as department chair from 1969 to 1971 and then retiring.

After the two units merged, the first chair of the joint-affiliated program, Jim Gaylor, made six hires within two years starting in 1978. Those hires included Wall, David Emerich, Frank Schmidt and Joe Polacco, who are still members of the department.

A group of faculty, including Schmidt and Polacco, pursued genetic studies using recombinant DNA. Their workspaces moved to the basement of the School of Medicine during the renovation of Schweitzer Hall in the ’80s.

“Life in the medical center was kind of fun because we were all pretty much iconoclasts at that time,” Schmidt says. “We were all children of the ’60s.”

The memories that Schmidt recalls of that time bring a smile to his face — like the summer days when former professor Jeff Robbins would wear shorts with his white lab coat and walk in the hospital’s public areas, much to the chagrin of the medical school administrators.

Then there’s the time that Polacco asked his colleagues to watch over the iguana he kept at his lab while he was at a conference — only to find it had passed away and was packed in plastic and put in the ultra-cold freezer after suddenly falling off of its perch.

Or the time that one of Schmidt’s first graduate students had started a fire that required a special powder fire extinguisher from the Columbia Fire Department to put out. Schmidt’s office happened to be directly above the office of Charles Lobeck, the dean of the School of Medicine at the time.

“And even though I was only an assistant professor, I got away with that,” Schmidt says.

Starting as a junior faculty member, Schmidt taught undergraduate classes, an opportunity he relished. He knew that at most universities someone in his position might be confined to giving a series of lectures to medical students. Teaching is a part of the job he still enjoys, Schmidt says.

“We have a large undergraduate program, and because a lot of our students are interested in medicine as a career, the access to the medical school helps a lot,” Schmidt says. “We end up teaching a lot, and I, for one, learn a lot of my science from having to teach it. I think most of my colleagues would say the same thing.”

The start of big collaborations

In 1981, MU sold land near Weldon Spring, creating a new source of funding for all four schools in the UM System. Shortly thereafter the chancellor at MU at the time, Barbara Uehling, announced that the money going to MU would be used to promote research.

Randall, who had been working with plant biologists in six different departments on campus, wrote a research proposal for three years of funding to start an initiative called the Interdisciplinary Plant Biochemistry and Physiology Group. That title would later be shortened to its current name, the Interdisciplinary Plant Group, or IPG. Under Randall’s leadership for 28 years, the IPG developed an international reputation.

When the Food for the 21st Century program (F21C) was established in 1983 by the State of Missouri, the IPG was able to achieve significant growth and financial stability by being annually funded as part of the plant biotechnology cluster of the program, following another successful proposal by Randall.

A few years after the start of F21C, Randall and others met with Uehling to talk about starting a similar program to the IPG but devoted to the growing field of molecular biology. Uehling agreed, beginning the Molecular Biology Program on campus. New faculty hired by that program could choose among several departments. Impressively, five of 10 hires chose MU Biochemistry. The successes of these interdisciplinary programs provided the foundation of what is now known as the Christopher S. Bond Life Sciences Center, a project that was spearheaded by former CAFNR Dean Roger Mitchell, among others.

“So MU Biochemistry has been a fundamental part of all this. With the IPG, we did have a number of the F21C hires choose us as a home,” Randall says. “We’ve been a core component of all of these life science programs.”

The IPG now has 60 members across the campus, including 13 members who are on the MU Biochemistry faculty. Two of the most recent members, Scott Peck and Antje Heese were working in England in 2005 when they received offer to be a part of MU Biochemistry and the IPG.

Peck, who works in signal transduction in plant proteins as an investigator at the Bond Life Sciences Center, says having colleagues who want to interact is “a huge plus.”

“It’s one of those things,” Peck says, who also serves as a professor of Biochemistry. “You come and you interview. Everybody’s talking very warmly about how great the interactions are. Even after you move here, after a while, you keep peeking under the rug expecting to find something, but it really is that atmosphere.”

Mick Petris, professor of Biochemistry, also conducts his research in the Bond Life Sciences Center. Since arriving at MU in 2000, Petris has become a renowned expert on a particular copper transporter gene, especially in relation to aspects of cancer tied to the enzyme lysyl oxidase, something that catalyzes crosslinking of connective tissue proteins.

O’Dell first researched this reaction after observing aortic rupture in copper-deficient animals in the ’60s. Aside from the environment and setup at the Bond Life Sciences Center, the overall ease to physically walk to any building on campus and have impromptu face-to-face interactions has been an invaluable asset to his work, Petris says.

“If you have to go and jump in your car in order to talk to someone and chat with them, there’s an obstacle there. But, if you can walk across campus or walk down a floor — or even better — sit in a room, then that’s a significantly lower barrier to doing research,” Petris says. “Yes, there’s Skype. Yes, there’s a phone call, but science sometimes works better in a less formal setting, such as brainstorming with a white board. Even in today’s times, there are certain things that are lacking in the digital wonderland.”

Building new bridges

If there’s any one person who understands how MU Biochemistry serves as a bridge between CAFNR and the School of Medicine, that person is Bill Folk. When Folk arrived at MU in 1989, his appointment was a 50/50 split between the two entities. When Folk served as chair of the department from 1989 to 2000, he maintained one office in the medical school and one in Schweitzer Hall.

“I think the key of maintaining that bridge is maintaining the excitement of the faculty for education and research and not settling for anything less than the best that we can do,” says Folk, a longtime IPG member who became just the third member of the CAFNR community to give the prestigious 21st Century Corps of Discovery Lecture a year ago.

With the help of Mitchell and Lester Bryan (then the dean of the School of Medicine), Folk and several other MU Biochemistry faculty members helped replace traditional teaching methods with problem-based learning (PBL) in the medical school curriculum in 1992. The PBL system has led to a better retention of core knowledge of basic science by MU’s medical school students since its implementation, Hazelbauer says.

“By the time they are taking their courses in the second year, they are doing significantly better than students in most other medical schools,” Folk says, “so we’re doing something right.”

After spending more than 30 years on different ends of campus, MU Biochemistry finally consolidated in December 2007 . That’s when a $10 million, 26,000-square foot addition to Schweitzer Hall, providing seven new laboratories, was occupied. The project also included a new bridge that connected Schweitzer to the Schlundt Annex with a lounge that serves as an informal gathering place for personnel. One of the highlights of the addition’s facilities was the unveiling of an imposing $2.1-million 800 megahertz nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometer on the ground floor. The NMR device, which has been referred to as an MRI machine for molecules, was — and still is — one of a few of its type in the country.

When Xiao Heng, assistant professor of Biochemistry, decided to come to MU in 2013, the state-of-the-art NMR instrument — that she uses regularly as a structural biologist specializing in RNA molecule research — was a major factor. But aside from the investment in technology, Heng was drawn in by the overall spirit of collaboration that she found while first talking with her future colleagues.

She recalled discussing future collaborations even during the interview process. When she joined the faculty, she quickly became part of a team of virologists, which allowed her to explore interdisciplinary research easier than she imagined.

“I have to admit that those collaborations really broadened my view as an assistant professor,” Heng says.

In the early afternoon of June 28, 2010, Judy Wall, who is one of Heng’s faculty mentors, was sitting in her office when she was startled by a loud explosion in one of her laboratory’s anaerobic chambers. The blast was caused by an accidental mixing of hydrogen and oxygen.

“I knew immediately what it was,” Wall recalls.

Four of Wall’s team members had to be taken to University Hospital to be checked; one had to be kept overnight. Later that night, then MU Chancellor Brady Deaton visited the hospital, as did Marc Linit, CAFNR senior associate dean, on behalf of CAFNR.

“The university was right on the money. They were here. They were unbelievably supportive of my group,” Wall says.

Within a week, Hazelbauer had managed to make arrangements so that Wall’s lab would be able to continue its work with a minimal hiatus. Within 10 months, Wall’s lab was back up and running.

“I feel eternally grateful for the support I’ve received, and it’s now my turn to be able to give back to the university when I’m asked,” she adds. “I very much appreciate the opportunity to do so.”

The endless pursuit of knowledge

Although the names and facilities have changed over the years within MU Biochemistry, the fundamental desire to learn something new remains the same.

“If you think about it 99.999 percent of the world will never be able to understand the new technologies and information that are being gleaned or the beauty of the experiments that are designed to actually explore biological sciences and life sciences,” Wall says. “I feel incredibly privileged to have that window and to be able to share that with my students and my post-doctoral fellows and to learn from them as time goes by.”

“You’re creating a piece of a jigsaw puzzle and you’re discovering something that no one has ever seen before,” Mick Petris says.

“I’ve always said that researchers seem to think that there are many more downs than ups and that there are a lot of disappointments, but when you do find an experiment that works and reveals something new, that’s the high point,” O’Dell says. “That’s what keeps people going.”

Hazelbauer says his favorite part about biochemistry is the fact that “you can learn new things from anybody,” ranging “from a very experienced colleague” to “a naïve but enthusiastic beginning student” to “anyone else in a research group or in the halls of the department. It’s one of the things that keeps all of us alive and, I think, young.”

Frank Schmidt has a habit of posing a problem to his students when he wants them to linger on it for a while in the classroom. “I’ll say ‘This will occupy you folks for the rest of your careers because we don’t know how this gets done, but we know it’s important. Now have at it.’ And I think that whole sense of an endless frontier is what keeps all scientists, but particularly biochemists, occupied and interested.”