It’s hard to find evidence of research excellence in the University of Missouri’s first decades. Tight funding, the chaos of the Civil War and a reluctance of established researchers to live on civilization’s edge hindered early attempts by MU to be more than a teaching institution.

There was one area of scientific investigation where Mizzou did quickly shoot to national and international prominence – the study of insects. In its first 100 years, MU entomology helped end a devastating grasshopper plague consuming the Plains states, identified the vector of a deadly cattle disease (and set the stage for pathogen research in human diseases), saved the European wine industry from destruction, and solved a lethal problem crippling the honey industry.

An Early National Reputation

Entomology at Mizzou began simultaneously with the founding of the University. Edward Leffingwell, MU’s first natural history professor (at an annual salary of $500 per year), was charged with offering the first instruction in insects.

Entomology was seen as an important part of MU’s mission even in those earliest days. The MU Catalog of 1844 proudly announced the University had been gifted the standard entomological textbook of the day, Thaddeus William Harris’ Insects Injurious to Vegetation.

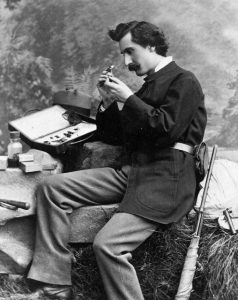

Missouri first stood on the national insectum stage in 1868 when Charles Valentine Riley (1843-1895) was appointed state entomologist and MU professor of entomology. Riley was famous for his work as artist and editor of the Chicago-based “Prairie Farmer,” a leading agricultural journal of the day.

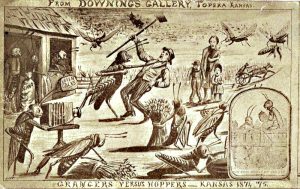

Riley’s drawings were as much fine art as scientific renderings. His prose blended science, acute observation, Victorian philosophy and poetry. He was the most famous insect expert in America. His series of scientific papers on the Rocky Mountain grasshopper and Colorado potato beetle, known as the “Missouri Reports,” became classics of American entomology. His observations and recommendations helped end a devastating infestation that was threatening to push settlers from their farms.

In April 1874, the MU Board of Curators requested that Riley create an insect museum to support scientific studies and serve as reference material. Riley used duplicate specimens from his personal collection and the State Board of Agriculture’s cabinet. Today’s Enns Entomology Museum is recognized worldwide and contains more than 7 million specimens.

MU’s entomology department earned another accolade during the great Texas to Kansas cattle drives. In the 1880s, the British journal Veterinarian described a “terribly fatal disease” that had broken out among cattle in the Plains states. Midwestern farmers knew it was associated with longhorn cattle driven north by Texas cowboys. The cattle appeared healthy, but Midwestern animals that shared pastures with the longhorns became ill and often died. Farmers called the disease Texas Fever.

During the years 1889-1893, T. Smith, E.L. Kilbourne and C. Curtice established that the disease was caused by a microscopic parasite transmitted by Boophilus ticks. This research, conducted at MU, was the first proven instance of an arthropod-vectored livestock pathogen. Their research paved the way for eradication programs that ultimately eliminated Texas Fever, and helped physicians understand the triggers of some diseases.

France Withers on the Vine

In 1878, MU College of Agriculture Dean George Swallow encouraged viticulturist George Husmann to join the faculty at the College of Agriculture. Swallow’s intent was to bolster Missouri’s flourishing grape and wine industry. The subject was already important at Mizzou – today’s White Campus was once 40 acres of thriving grape rows. Memorial Union, the Agriculture Building, Bond Life Sciences Center, Mumford Hall, Lefevre Hall and surrounding buildings were built on what was originally vineyard soil.

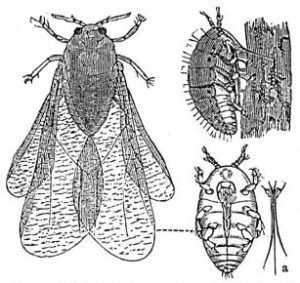

Husmann and Riley were among scientists from all over the world called upon to help investigate the Great French Wine Blight. French vineyards were dying and it looked as if the entire European industry would be wiped out. The Missouri soil and insect experts identified the aphid phylloxera, a small, sap-eating and greenish insect, as the culprit. Riley and George Englemann, a German-born colleague, quickly determined that it was not possible to eradicate the insect once it was established. Instead, they had to learn how to live with it, and the only way was to graft French vines onto the immune American rootstocks.

Husmann and Hermann Jaeger, a winemaker from Neosho, acted on Riley and Englemann’s recommendations. Grafting the more sensitive French vines onto hardy American rootstocks created immunity to the aphid. An estimated 10 million rootstocks, mostly Vitis riparia and Vitis rupestris grown in nurseries in Neosho and Sedalia, were shipped to France.

Husmann, Riley, Englemann and Jaeger had saved the European wine industry. They were feted as heroes by the French, receiving the Cross of the Legion of Honor.

Agricultural Education Growth

Even with its research successes, entomology education at MU was just an adjunct to the University’s biological class offerings, according to Entomology at the University of Missouri, published in 1994. Enrollment was small. In fact, only two courses were offered each year.

That changed in 1895 with an invasion of Missouri by the San Jose scale, a winged insect that infested Californian fruit trees. The University and Missouri Legislature boosted funding and faculty positions, creating an official Department of Entomology. By 1908, there were 41 students seeking their MU entomology degrees.

In 1915, curricula leading to master’s and doctoral degrees were offered. One of the first master’s degrees was conferred to A.H. Hollinger, whose research helped Missouri farmers rid their fields of the San Jose scale infestation.

Serving Missouri Farmers

Even with a small faculty, MU entomologists were helping the state’s agricultural interests. As early as 1895, Extension programs taught farmers how to control the chinch bug, a grass pest that migrated from Texas. MU extension entomologists dispensed one million gallons of federally-obtained chinch bug oil, which saved enough forage to keep most of Missouri’s livestock herds intact.

Later, best practices to deal with crop threats such as the Hessian fly and the corn earworm were distributed to the state’s farmers.

In 1944, the deadliest disease to strike honeybees came to Missouri. Called foulbrood, the infection was caused by spores in the bee’s food. The only known early cure was to burn infected hives.

Two MU researchers, Leonard Haseman (1884-1969) and L.E. Childers, determined that feeding honeybee colonies a diet containing sulfathiazole (a sulfa drug developed to cure battle wound infections in World War II) protected the bees against foulbrood. This saved millions of dollars of the nation’s apiculturists.

Collaborating for the Greater Good

Working across disciplines is nothing new to MU entomology. In 1941, St. Louis Physician G.W. Bock donated his notes and collection of 300,000 beetles – many agriculturally useful – to MU. Another St. Louis medico, E.P. Meiners, shared his collection of 35,000 insects, some known to be dangerous to humans. In 1957, MU’s Curtis Wingo (based at the then-new Delta Research Center in Portageville) worked with colleagues at MU’s School of Medicine to establish that the brown recluse spider was the cause of dangerous necrotic lesions spreading from the south-central U.S. and into the Plains states.

Philip Carlton Stone (1911-1968) worked with T.D. Luckey of MU’s Biochemistry department in a human nutritional study. Stone’s contribution detailed the process of hormoligosis (growth stimulated by small amounts of material that becomes harmful in larger quantities) in crickets as a model for human reaction.

Into the 21st Century

In August 2005, Agriculture Dean Roger Mitchell (1932-2013), as part of a larger effort to inculcate such collaborative efforts into the very administrative structure of the College, merged the departments of entomology, agronomy, horticulture and plant pathology into the Division of Plant Sciences. Mitchell also changed the MU College of Agriculture to the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources. To Mitchell, it wasn’t just a signage issue, but an evolution in mission and philosophy.