When agricultural scientists talk about increasing crop yields, the name of CAFNR’s William Albrecht usually pops up. When health researchers discuss some of the most vexing chronic illness of our day, Albrecht is mentioned, too.

As Chairman of the Department of Soils from the Depression through World War II and into the ’70s, Albrecht was the foremost researcher on the relation of soil quality to human health. As emeritus professor of soils, he continued to draw direct connections between poor quality forage crops and ill health in livestock and people.

Pioneering Interdisciplinary Research

William Albrecht (1888–1974) was born of German ancestry on a prairie farm in north central Illinois. He attended the University of Illinois where he obtained a degree in liberal arts. This led to a job teaching Latin and other subjects at Bluffton University, Ohio.

Albrecht returned to U of I to earn a second undergraduate degree, this time in biology and agricultural science, followed by graduate research in botany. His doctoral research, “Symbiotic nitrogen fixation as influenced by nitrogen in the soil,” was published in the influential journal Soil Science in 1920, garnering him national attention.

Albrecht joined the MU College of Agriculture’s soil faculty in the 1930s and soon became the department’s chair. Almost immediately, he began to add studies linking soil and human health to his expected research to improve crop yields.

He soon became the concept’s leading authority. As President of the Soil Science Society in 1938, he wrote in the Yearbook of Agriculture that “a declining soil fertility, due to a lack of organic material, major elements and trace minerals, is responsible for poor crops and in turn for pathological conditions in animals fed deficient foods from such soils. Mankind is no exception.”

In his 2011 William A. Albrecht Lecture at Mizzou, fellow MU soil scientist John Ikerd observed that such a linkage was controversial and Albrecht risked his academic reputation by warning of the public health risks posed by poor soil and fertilizer-intense agriculture. Albrecht had ventured beyond his narrow academic field, during a time when it was unheard of to do so, to rethink the science involved, and perhaps redefine their disciplines.

History provides compelling evidence that Albrecht was right, Ikerd said. “A half-century later, America is facing an epidemic of diet-related illnesses, including obesity, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension and various forms of cancer,” he said. “If current trends continue, the cost of health care, which is already nearly twice the cost of food, will claim more than one-third of the U.S. economy by 2040. Recent scientific studies have linked a decline in the nutritional value of foods with the industrialization of agriculture. The result is foods rich in calories but poor in essential nutrients. As Albrecht had warned, the declining health of our people may well be a biochemical photograph of the declining health of our soils.”

A Soil Scientist Studies Teeth

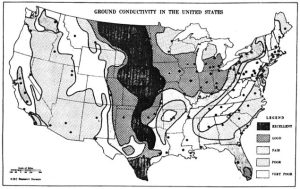

As a scientist, Albrecht was fearless, immune to criticism by his traditional colleagues, and went where his data took him. Perhaps his most controversial, and most important, study was a review of World War II-era dental records of 70,000 sailors.

Albrecht was out to prove his hypothesis that poor soil triggered poor nutrition resulting in poor health. He saw an opportunity by studying dental problems. He sought a link with the health of sailors’ teeth to the health of soils in their native regions of the U.S.

“In those days, people mostly ate foods grown on local farms or at least grown in their respective regions of the country,” Ikerd said. “Albrecht concluded, ‘if all other body irregularities as well as those of the teeth were so viewed, it is highly probable that many diseases would be interpreted as degenerative troubles originating in nutritional deficiencies going back to insufficient fertility of the soil.’”

At the end of World War II, Albrecht called for a major national initiative to restore the health and fertility of America’s “worn out” soils. Few listened. Instead, the nation’s agricultural priorities shifted to producing more and cheaper food.

Albrecht anticipated that reliance on commercial fertilizers to increase production would degrade both soil health and human health. “He was particularly concerned with an overemphasis on nitrogen, phospherous and potash would lead to depletion of trace minerals, such as manganese, copper, boron, zinc, iodine and chlorine and degrade basic soil health,” Ikerd said. “He wrote that N P K formulas, as legislated and enforced by State Departments of Agriculture, ‘mean malnutrition, attack by insects, bacteria and fungi, weed takeover, crop loss in dry weather and general loss of mental acuity in the population, leading to degenerative metabolic disease and early death.’”

Obesity and Soil Health?

America was still a slim nation when Albrecht died in 1978. Before his passing, Albrecht predicted that we would soon get fat. He said people were functionally malnurished by poor quality food. We would overeat to get enough nutrients.

He was right. Recent statistics classify two-thirds of adults and nearly one-third of American kids as obese or overweight. Since Albrecht’s death, the number of obese adults has doubled. Since 1970, the number of obese adolescents ages 12-19 has tripled and the number of obese children ages 6-11 has quadrupled.

Obesity, Albrecht pointed out, is more than just feeling uncomfortable in your clothes – obesity triggers several diet-related diseases, including diabetes, heart disease, hypertension and a variety of cancers. He predicted that this would not only diminish the length of lives of people, but also create a huge economic burden. Ikerd in 2011 said Albrecht’s prophecy has been fulfilled. Today, obesity-related illnesses will claim about one-in-five dollars spent for health care in America by 2020 – erasing virtually all of the gains made in improving public health over the past several decades.

Ikerd pointed out that, according to USDA research, per capita consumptions of fruits and vegetables have been basically flat over the past 40 years, the period of increasing obesity. What is significant, Ikerd said, is a decline in consumption of fresh produce has been offset by increases in consumption of processed fruits and vegetables. “Interestingly,” he said, “home gardens accounted for about 25 percent of all vegetables eaten in the early 1900s, but accounted for less than three percent of total vegetable consumption in the late 1900s. This might logically suggest the soil on which vegetables are grown is more important than the quantity consumed.”

A study was published in the Journal of American College of Nutrition in 2004 compared nutrient levels in 43 garden crops in 1999 with levels documented in historic benchmark nutrient studies conducted by USDA in 1950. Declines in median concentrations of six important nutrients were: protein -6 percent, calcium -16 percent, phosphorus -9 percent, iron -15 percent, riboflavin -38 percent, and vitamin C -2 percent.

Albrecht’s analysis of the obesity problem is shocking and controversial even today — Americans overeat not because they are lazy or stupid, but because their food leaves them nutritionally undernourished and they eat more to compensate.

Go Food and Growth Foods

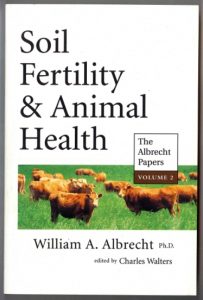

As an emeritus professor, Albrecht became even more outspoken in his conclusion regarding the linkage between soil health and human health.

In 1966, he pointed out that the health of the soil affects the nutrient balance between proteins and carbohydrates in both feed and food crops. Furthermore, he concluded, only healthy organic soils with the proper balance of both macronutrients and micronutrients could produce the complete proteins necessary for good human health.

He distinguished between the “grow foods” grown on healthy soils and “go foods,” which were filled with carbohydrates for energy but lacking in the complete proteins needs for growth and health. “Go foods” make humans fat; it takes “grow” foods to keep humans healthy.

Ikerd said he doubts Albrecht would be surprised by the epidemic of obesity and other diet-related health problems confronting Americans today.