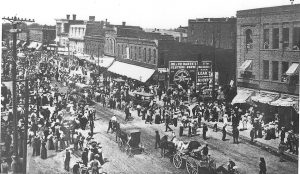

In 1919, downtown Columbia was jammed with people and horses. The small town of just 10,000 had been invaded by more than 4,000 visitors, all scurrying for something to eat or to get to the next lecture. It was a scene that was re-enacted, to one degree or another, each year between 1910 and 1957.

Farmers’ Week was an idea to build the reputation of the struggling MU College of Agriculture. It succeeded wildly, becoming one of the largest agricultural events in the nation. Before the program faded after World War II, almost 10,000 people annually would visit Mizzou to hear agriculture faculty describe their latest research findings.

A New Dean Hatches an Idea

In a Missouri Alumnus magazine story, MU historian Jesse Wrench said the idea of Farmers’ Week originated in 1909 with Agriculture Dean Frederick Mumford.

The College’s winter short courses for farmers were successful, but small, even timid. Dean Mumford envisioned a big affair to bring together farmers, agricultural researchers and industry professionals. He wanted a new collaboration where his half-dozen faculty could showcase their research and get feedback.

Attracting new students was another goal — and challenge. Many Missouri farmers thought the very idea of a college teaching agriculture was foolish – the best training for a youngster was dawn-to-dusk on-the-job labor in the fields. Consequently, early MU College of Agriculture enrollment was sparse – only six students enrolled in its first year in 1871 and 29 in the second year. In 1895, there were still only 41 official students.

Dean Mumford’s vision for Farmers’ Week went beyond faculty delivering lectures. He wanted the show to be run by students. This would give them planning, budgeting and administrative experience, and spotlight them as leaders who could do more than walk behind a mule and plow.

Cowboys, Indians and Agriculture

That first Farmers’ Week in 1910 got off to a strong start. More than 200 farmers and professionals registered. Industry displays from as far away as Chicago included new plows, cultivators and seeds. Professors in shirts, ties and bowler hats rubbed elbows with farmers nervous about being on a university campus. The event also attracted dozens of high school students “to see the Missouri spirit at its best and get to know some of the things that Missouri ag students do during the year,” the Savitar yearbook reported.

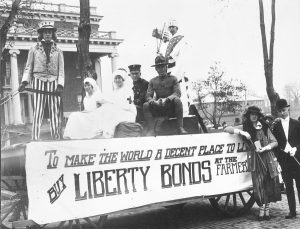

That Savitar article noted the fair began with a “mile-long” parade led by the Goddess of Agriculture. “After winding through the Columbia business district, and the two campuses, the parade ended at ‘the pike’ where the atmosphere of a county fair was in full swing.” The two campus reference refers to the red and white campuses – the red brick for the liberal arts MU and the white limestone of the MU agriculture campus. The pike was a collection of industry and student displays held on ground now occupied by the MU Animal Sciences Research Center.

A parade wasn’t supposed to be part of the event. It started with a misunderstanding.

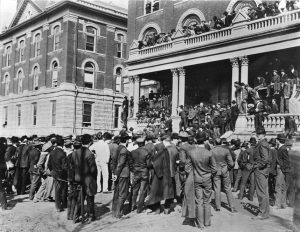

With permission from Mumford, agricultural students dressed in their overalls to chapel on the first fair day. President Richard Jesse, unaware of the festivities, met the students outside and blocked their entry. The surprised students (and curious onlookers) gathered on the south steps of the administration building (now Jesse Hall) where Jesse chastised them for their disrespectful garb and ordered them to disband. They did and then paraded downtown with every available farm implement in tow. Jesse was then told of Farmers’ Week and apologized the next morning

The Savitar reported the parade featured students in “odd and sarcastic” costumes and “drinking gallons of pink lemonade.” The Savitar said some students dressed up “as a squad of cowboys in leather chaps, sombreros and gaudy skirts astride pinto ponies and chased a tribe of Ag School Indians with six-shooters blazing away.”

Despite that tomfoolery, MU – and Jesse – quickly supported Farmers’ Week. The Mizzou Marching Band and Men’s Glee Club proudly performed. Most of the scarce MU buildings were made available for lectures and displays.

Event planning made students create sub-committees that influenced the later establishment of future CAFNR academic divisions. The Dairy Club, Horticulture Club, Agricultural Economics Club, Short Horn group, Home Economics Club and other student organizations created displays for visitors. Students divided attendees into agricultural interests and led them to lectures by appropriate members of the College faculty.

Attendees ate it up. “Some faculty members would sometimes lecture practically all day,” reported A Century of Missouri Agriculture, a Bulletin of the University of Missouri Agricultural Experiment Station published in 1958.

Farmers’ Week Grows Quickly

The third Farmers’ Week, 1913, saw more than 800 farmers from 104 of Missouri’s 114 counties represented, as well as visitors from 12 other states.

A month later, the Missouri Alumnus magazine reported that half a dozen colleges had written to W.L. Nelson, assistant secretary of the State Board of Agriculture of Missouri, asking for details to get their own weeks started. In 1914, Kansas State and Nebraska’s colleges of agriculture started similar fairs. The Nebraskans seemed particularly intrigued with the Ham and Bacon show, something they lifted whole hog into their program.

Lectures and demonstrations at Mizzou included Dairy Herd Management, Composition of Commercial Fertilizers, Farm Bee-Keeping, Judging Horses for Soundness, Management of Corn Soils and How to Sell Timber. The Women’s Section had programs on General Principles for Selecting Food, Planning the Daily Menu and Bread Making.

The Boys’ and Girls’ Section included Games for Rural Boys and Girls, Livestock Judging and a data-heavy lecture entitled Man and the Domestic Animals by the unsmiling Dean Mumford.

Farmers’ Week was not limited to agriculture subjects, as noted by Missouri Alumnus. In 1913, the now retired Richard Jesse spoke on women’s right to vote as president of the Equal Suffrage Association of Columbia.

And things were just getting started.

In 1914, Farmers’ Week surpassed 2,000 participants. In 1915, 2,810 would register to hear U.S. Secretary of Agriculture David Houston give the keynote address. Also in that year, a State Baby Show was held. Floyd Tuttle, the three-year-old son of Dr. and Mrs. Floyd Tuttle of Mt. Leonard, Mo., was judged Missouri’s Most Perfect Baby. Judges were animal sciences faculty who generally bred cattle.

In 1916, Missouri Governor Elliott Major proclaimed: “Missouri’s Farmers’ Week is the best and greatest institution of its kind in the United States for the development of the country at large. There is no other factor in the general progress of the nation that exerts so much force than the bettering of economic conditions as this annual meeting of the producers of the necessities of life.”

1916 was also the year Farmers’ Week attracted international attention. David Lubin, founder of the International Institute of Agriculture in Rome, Italy, addressed students and farmers on international farm practices and marketing. Eighteen U.S. ag associations were involved in 1917.

World War I and Farmers’ Week

Missouri was an important farm state helping feed America. With the disruption of European agriculture caused by World War I, Missouri became even more important.

In 1918, when participation passed 3,000, President Wilson’s War Council attended Farmers’ Week to ask the state’s farmers to do everything possible to boost food production.

They included Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo; Herbert Hoover, national food administrator; Sir Frederick Smith, attorney general of the United Kingdom; George Vincent, president of the Rockefeller Foundation; Thomas Wilson, president of Wilson and Company Packers; Charles Barrett, president of the National Grange; and Carl Vrooman, assistant secretary of agriculture.

In 1919, more than 4,000 came to Farmers’ Week, swamping Columbia’s population of 10,000. The Wabash and Missouri-Kansas-Texas railroads commissioned special trains to bring in the throngs, and Ford’s Model T made Farmers’ Week just a day’s drive away by previously isolated farmers.

Despite the hassle, Farmers’ Week was a big economic deal to the city. In most years, a huge banner saying “Hello Mr. Farmer” was hoisted over the red-bricked Broadway. Hotels filled quickly and families made extra money renting rooms by the day.

In 1920, Pathe News hired a biplane to take aerial footage for a news short that was shown in movie theaters nationally.

MU agriculture students that year earned receipts of $4,284 — $1,000 more than the event cost.

The 1922 Savitar proudly said MU’s Farmers’ Fair had “grown from a parade of farm machinery to the ‘Biggest Student Stunt in America.’ The fair is managed, financed and directed by agricultural students without outside assistance.” The story also notes that fair profits were donated to help build MU’s Memorial Union.

Farmers’ Week also helped achieve Dean Mumford’s goal of growing the College’s student population. The student population reached 664 in 1920, making agriculture the biggest single academic unit of Mizzou.

The Tradition of the Farmers’ Banquet

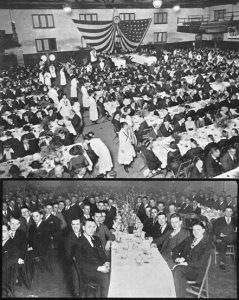

One evening of Farmers’ Week was given over to the Farmers’ Banquet. It was held in Rothwell Gymnasium, and sometimes was attended by a thousand people.

For most years, preparation was handled by Professor P.F. Trowbridge, chairman of the Department of Agricultural Chemistry. Roast beef was served from prime animals of the College herd. Professor Trowbridge had these roasts prepared, cooked in the ovens at the homes of agricultural faculty, and rushed hot to the banquet tables.

At each long table a faculty member sat at one end, acting as host and carving the roast with “many second and third servings provided,” contemporary accounts remember. The professor’s wife sat at the other end of the table and acted as hostess. Waiters and waitresses were students of the College.

The banquet, unavoidably, was accompanied by speeches from university officials and dignitaries. “Those who were privileged to attend Farmers’ Week banquets talk about them to this day,” reported A Century of Missouri Agriculture. “They were very well organized, the food was excellent and all was very enjoyable.”

A Corn Time Capsule in Waters Hall

State agricultural organizations supported Farmers’ Week from the beginning. One of the most important was the Missouri Corn Growers’ Association. Interest in corn developed greatly during this time with Farmers’ Week delivering the latest discoveries.

In 1926, Waters Hall was under construction. The corn growers’ association offered a prize for the best ear to be placed in the cornerstone of the building. Corn from across Missouri competed and were judged according to a score card of the day, reported A Century of Missouri Agriculture.

“This card was then wrapped around the winning ear, which was placed in a copper tube and hermetically sealed,” the bulletin noted. “It still lies in the cornerstone of the building, for scientists, or possibly archeologists, of the future to puzzle over.”

In 1928, it was decided to hold the event in October instead of January – the automobile had become popular and people wanted to drive during good weather. Nineteen-hundred and twenty eight was the pinnacle year for Farmers’ Week with an estimated 10,000 people attending.

The Depression and World War II Mortally Wound Farmers’ Week

The Depression was a tragedy for American cities, but it was particularly hurtful in rural Missouri. When banks failed after Black Tuesday, Oct. 30, 1929, many farmers woke up to find their life savings gone. Three hundred banks closed in Missouri alone, and the state’s manufacturing declined in value from $600 million to $339 million. Retail sales dropped by 50 percent. Only three banks in northern Missouri survived the onset of the Depression – but none could loan money to farmers to buy seed or pay farmhands.

Farm production plunged due to low prices. Farmers fought chinch bug infestations and grasshopper plagues. Participation in Farmers’ Week dropped to 2,000, then 1,600.

Numbers stabilized in the late ’30s, but the World War II draft emptied farms and College of Agriculture classrooms. Gasoline rationing and priority travel given to servicemen reduced Farmers’ Week to just essential short courses.

A rump Farmers’ Week continued into the ’50s, but even that was fading. By this time MU Extension was mailing scientific discoveries to farmers directly. A Farm Forum on Public Policy, an open discussion of farm policies as influenced by federal and state activities, pretty much substituted for Farmers’ Week. The last MU Farmers’ Week was held in 1957.

More Farmers’ Week Photos