Students stroll by Eckles Hall without a second look. If they notice it at all, it’s to see if Buck’s Ice Cream is open.

The building, now part of the Food Science and Engineering Division, represented a huge investment by the Missouri Legislature to boost Missouri’s agricultural economy through dairy teaching and research. Where students now walk, some of the most productive cows in the world once grazed.

Five Cows and a Bull – Dairy Science Comes to MU

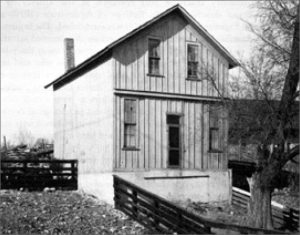

MU dairy research was born in 1887 when Dean J.W. Sanborn (the second dean of agriculture, 1882-89) purchased five Jersey cows and a bull and grazed them on the pasture where Eckles Hall now stands. State funds being tight, in 1890 he converted a nearby farm house to be MU’s first dairy building.

Dean Edward Porter (dean of agriculture, 1889-95) scraped together funds to fit the two-story structure with a cream separator, hot and cold water, a churn and a “butter worker.” With this wealth of research tools, the first University publication – Bulletin 26 – was published in 1894 by the MU Agricultural Experiment Station (which had been established in 1888). This paper gave directions on the care of milk, how to make butter on the farm and the importance of ongoing record keeping. This publication was one of MU’s first research reports to be widely recognized.

The house, where the first course in dairying was offered in 1895, was soon inadequate with a booming dairy student body. The 41st Missouri General Assembly stepped in to help – big time. First, it appropriated $40,000 for the construction of “laboratories for livestock judging, dairy instruction and veterinary science.” Then, it enacted a law establishing a department of dairy husbandry within the College of Agriculture.

That $40,000 shows how important the legislature considered dairy research and teaching in Missouri. Just three years before, $50,000 was allocated for the building of Jesse Hall.

Professor Clarence H. Eckles, who held a master’s degree from Iowa State College, was selected to head the new department in June 1901. He would serve in that capacity until 1919 when Professor Arthur Ragsdale took over leadership and continued in that role until 1961.

The Dairy Science Building Gets the Program Moo-ving

Forty grand bought a lot of building in 1901. The Dairy Science Building was a two-story limestone building that housed several classrooms, a dairy chemistry lab and faculty offices. Its large windows were a technological marvel in the days when glass makers struggled to reliably make panes more than 12 by 12 inches in size.

An operational dairy plant was included and nearly 600 students were involved in testing, butter making and cheese making classes. Dairy products produced in the building were sold locally and to the University in MU-labeled wax paper cartons.

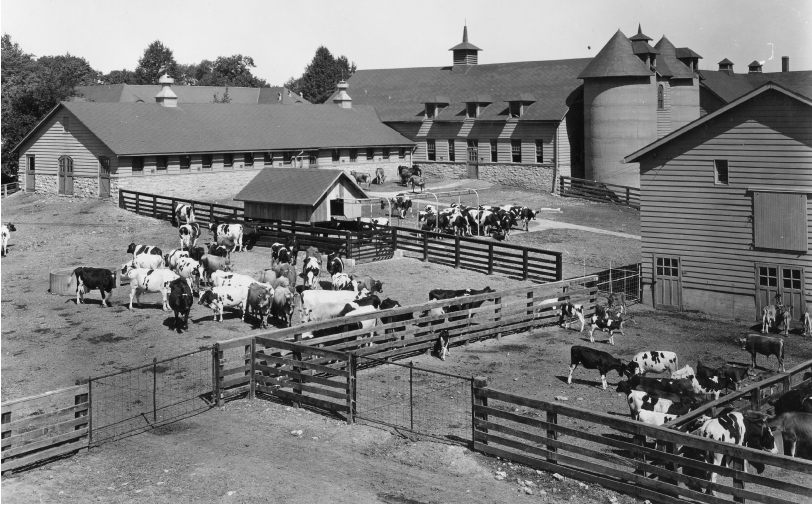

Eckles was an enthusiastic program builder and he promoted its successes at every opportunity. In a 1910 national magazine article he bragged that five of his Holstein cows produced an astonishing 101,612 pounds of milk and 3,879 pounds of butter in one year.

MU Dairy Husbandry professors must have had a good eye for stock. Worldwide attention was brought to Missouri in 1910 by a record-holding Holstein cow by the name of Missouri Chief Josephine. “Old Jo” as she was fondly known, produced 26,861 pounds of milk, containing 740 pounds of butterfat, in one year, which was the second best record in the world. She held the world’s record for 30, 60, and 90 days’ milk production, too.

Old Jo was a natural recruiter. An out-of-state student was asked by Professor Eckles how he had come to hear about MU. He replied: “I don’t know much about Missouri, but I do know about Chief Josephine and her world records. That’s why I came here!”

A bigger facility meant winter courses in dairying could be established. These appealed to farmers because they were offered during the slow time of the farming year.

Of Course We Won – We’re the Only Ones Who Came

An enthusiastic dairy student body also helped the MU College of Agriculture gain distinction. They were the winner of a national Intercollegiate Dairy Cattle Judging contest, albeit in an unusual way.

The contest was held in 1907 at the National Dairy Show in Chicago. Because of bad weather, no other teams appeared. The Mizzou team staged a competition among themselves, and declared themselves the winner.

The investment in dairy at MU began to pay off. Research resulted in discoveries that aided farmers in improving their dairy herds, increasing milk production and enhancing the profitability of the regional dairy industry. One important discovery showed that the best cow for milk production was not the one with the best coefficient of digestion – a common assumption then. Another study determined optimum nutrition levels of carotin in the milk fat and lactochrome in the whey. The results of this study formed the foundation for later research that revealed carotin as Vitamin A and lactochrome as Vitamin G.

The Dairy Science Building was renamed to honor Eckles. In 1938, the hall was expanded. It underwent a mechanical renovation in 1985, and it was significantly expanded on the east side to include the William C. Stringer wing.

After World War II, MU would become a leader in dairy and ice cream research and teaching. MU-branded milks, butter and cheeses, and three flavors of ice cream — vanilla, chocolate and strawberry – were created in Eckles Hall and consumed in University dining halls.

That all changed during the recession of the early 1970s when state funds dried up. Research into ice cream was begun, but that wasn’t enough to keep the department going. After the dairy plant closed in 1972 due to University fiscal problems, sales of MU dairy foods, including ice cream, stopped, too. Dairy Science diminished and Eckles was repurposed as a center of Food Science.

But that’s another story.