Each day, hundreds of students walk through the Agriculture Building’s courtyard without noticing a Mizzou artifact slowly moldering in the dirt. A survivor of the famous University of Missouri Academic Hall fire of 1892, the relic floated around campus for almost a century before mysteriously ending up in the courtyard. No one knows why the thing is there.

The artifact, a shadow of its original 30-ft. length, is a whale jawbone, reportedly from an animal harpooned off Greenland in the mid-1800s. The bone, like a stuffed elephant that would give Mizzou and the Missouri Legislature grief in 1889, was part of a natural history museum championed by one of MU’s earliest and most controversial administrators.

The whale bone’s journey to CAFNR has been a long and strange one. It begins with the president of the University of Missouri from 1876 to 1889.

Samuel Laws and His Dead Elephant

Samuel Spahr Laws (1824-1921) made a fortune as the inventor of the Laws Gold Indicator, a predecessor of the ticker tape machine.

In 1863, Laws, manager of New York City’s Gold Exchange, invented the indicator to end the crush of messenger boys scurrying in and out of the Exchange with the latest gold price. As the price changed, an electrical signal sent from the trading floor caused a hand on the indicator to point to the latest price.

Laws became wealthy and exercised his interest in higher education, first being named president of Westminster College in Missouri (where he was fired over a student drinking scandal). In 1876, he began his 13-year position as University of Missouri president.

His interest in science lead to the establishment of the School of Engineering and Laws Observatory, the first observatory west of the Mississippi. He also acquired the Thomas Jefferson headstone.

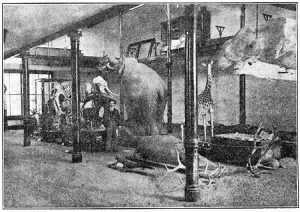

Laws personally oversaw the creation of his beloved natural history museum in Academic Hall. As recorded in the pencil-written minutes of the Board of Curators’ Feb. 1, 1886 meeting, Laws recommended the purchase from Professor Henry Ward, a naturalist, a collection of specimens that included a stuffed gorilla ($450), African zebra ($110), grizzly bear ($80), Canadian caribou ($75) and a sperm whale mandible ($10). The curators authorized Board President James Rollins to spend $2,500 for the collection.

Two years later, Laws added a giant Asian elephant to the collection. It would cause his resignation from MU.

That elephant, owned by Ringling Brothers Circus and named “The Emperor,” died of tetanus in Liberty, near Kansas City. Laws acquired the corpse for $1,680, and shipped it to a taxidermist in New York, intending to personally finance the work.

While the dead elephant was in New York, Laws lost his fortune speculating in the Kansas City real estate market. When the elephant’s stuffed carcass and articulated skeleton arrived at MU, Laws didn’t have the necessary funds. He sent the $1,100 invoice to the Board of Curators, who paid it. Opponents accused Laws of mismanagement. A legislative committee grilled Laws, who refused to resign. Governor David Rowland Francis (MU’s Francis Quadrangle is named in his honor) threatened to withhold University funding as long as Laws remained president.

Laws resigned in May 1889 and moved to Kansas City to write books. He was succeeded as MU president by Richard Henry Jesse.

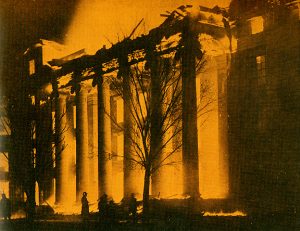

The whale bone, elephant and other exhibits remained enshrined in Academic Hall until fire destroyed the building in January 1892. Students braved the flames to pull artifacts into the snow.

A Well Traveled Bone

As best can be determined from old newspapers and magazines, the rescued remnants of the natural history museum were next displayed in Switzler Hall until 1913, when they were moved to the basement of the new LeFevre Hall.

The whale bone may have been separated from the other artifacts. According to the January 1941 issue of the Missouri Alumnus magazine, the jawbone ended up hanging in Swallow Hall. The editors offered a reward of a subscription to anyone who could provide information about it.

The elephant stood in LeFevre until the building’s renovation in the late seventies. By then, it had badly deteriorated and was thrown away. A comparative anatomy instructor pulled some of the bones out of the dumpster. Only two legs and the lower jaw were in good enough shape to be saved — they now on display on the second floor of Stewart Hall. It may have been then that the whale jaw was evicted from Swallow.

The College of Agriculture’s Forgotten Gardens Gets a Gift

At about that same time, three students, including William Ruppert, now president of the National Nursery Products company, St. Louis, received a $13,533 grant from MU’s Student Fee Capital Fund to create gardens from where the Anheuser-Busch Natural Science Building now sits to the Agriculture Laboratory Building. Five gardens were created – a Rhododendron Garden, Native Woodland Garden, Floral Display Garden, Rock Garden and Oak Grove Garden.

The Native Woodland Garden featured plants native to the Missouri Ozarks region – a miniature living model of this habitat. The upper level simulated the limestone of a bluff, and was planted with Yellowwood, Dogwood, Fringetree and Ironwood trees. A streambed was built to meander along the base.

David Trinklein, associate professor of horticulture, was a new faculty member then and was there during the creation of the gardens.

One day, Trinklein doesn’t know why, the whale bone was trucked in to be made part of the Native Woodland Garden. He said the whale bone confused everyone, particulary the horticulture professor then, Ron Taven.

“There were rumors that it was traded for a bronze sculpture or was just forced onto the horticulture students because no one else wanted the thing,” Thinklein said. “It’s a non sequitur,” he continued. “Why should there be a whale bone in an Ozark Garden?”

Students made the best of the unusual gift, incorporating it into the design, but hiding it under a thatch of trees.

Beverly Spencer, now executive staff assistant in the Dean’s Office and horticulture student then, helped build the rock foundation that the whale bone sits on. This made the bone into a bench, the best use anyone could think of to do with it.

Quietly Deteriorating in Place

Construction of ABNR destroyed four of the five gardens built by the horticulture students. The Native Woodland Garden and the whale bone were left in situ as their spots weren’t needed for the new building.

For almost three decades, the bone has sat in its tree-shaded home. Visitors pass by it without a second glance, thinking it’s a fallen tree or long rock.

The artifact that survived the Academic Hall fire has now turned gray and is chipping away. The iron hooks that once held it aloft in Academic Hall are rusted and one has fallen off. Spencer noticed that a hunk of bone has gone missing recently — perhaps it’s journey has not yet ended.

NOTE: Contact CAFNR Communications if you know anything else about the whale bone. We’ll reward anything we share next month in Inside CAFNR with a gift from the CAFNR Store.

Click here to view William Ruppert’s slideshow showing how the Woodland & Floral Gardens were built.