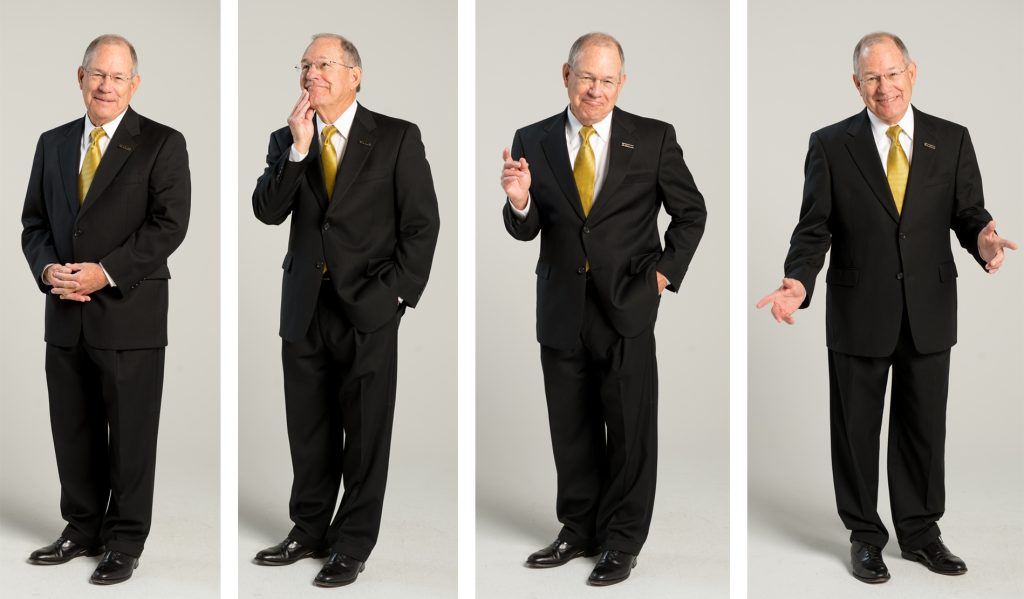

Everyone knows about the smiley face. It is part of the brand of Vice Chancellor and Dean Tom Payne. Looking at all of the related memorabilia in his office, one can see how the symbol has become synonymous with his infectious optimism and enthusiasm he has used over the past 18 years to help guide the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources through good times and bad.

“I wanted to add a little more emphasis and so I wrote my name ‘Tom’ and put the smiley face on it and it just took off from that,” Tom says of a note that he sent to a student while serving as a professor and head of the entomology department at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech) from 1987 to 1993. “If the smile I put in doesn’t look right, we retype the letter because I want it to mean something.”

“When he brought it here of course it caught on,” says Linda Holsinger, who has served as Tom’s executive assistant since his arrival and has worked with a total of seven deans (including three interims) since coming to MU in 1974. “You can’t help but smile when you see it. He uses it every time when it’s appropriate.”

“I think it always brought about a sense of ease, a relaxation of the shoulders among audiences he was with,” says John Gardner, former associate dean of research and outreach at CAFNR.

If Tom had adopted a second symbol, it might have been a tool box or a tool belt — icons fitting for a man who has never found an obstacle he could not overcome or task he could not complete.

Ask his son Jacob, and he’ll tell you of a father who is handed “a list of things to work on” when he visits his son’s Denver home “because he doesn’t want to stay still.”

When Tom and his wife (of now 54 years), Alice, moved to the Texas countryside in the mid-’70s after he took a job as an associate professor of entomology and forest science at Texas A&M University — they were greeted by a half-finished house after its contractors left the job without notice after going bankrupt. In a world well before the dawn of instructional YouTube videos, Tom quickly looked at examples of the parts of the house that were complete, conferred with others, and then put up sheet rock, built cabinets and installed electrical wiring, among other projects.

“You hear that expression ‘you’re mechanically inclined.’ I just basically can figure things out. There’s nothing mystical about it. You just figure out how to do it.” Tom says. “I don’t think anything is impossible and it’s because anything that’s broken, you can mostly figure out a way to fix it and I just figure that I’ve never run up against a brick wall because you can always figure a way around it.”

But when thinking back to his large achievement of finishing the home, he shares the credit with all of the friends and colleagues from Texas A&M who helped him along the way.

“It was a learning experience, and a lot of people helped,” Tom says.

“Oh my goodness, yes,” Alice adds.

Over his career, this same unbreakable “fix-it” attitude — combined with a deliberate balance between home and work life, and a personality blending charisma, impulsivity and humor — has proven to be a critical component in overcoming obstacles as well as the construction of a variety of professional and personal relationships.

“I think his career and his life-long friendships have been about building connections with people,” says Jacob, who often talks about leadership tactics with his father as a senior vice president at U.S. Bank. “I think my dad has a really strong ability to empathize with people and try to really understand what their wants and needs are in regards to a particular situation.”

“Tom epitomizes somebody who is a scholar and a gentleman, and one who brings levity to what he does,” says Sonny Ramaswamy, director of the USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, who has known Tom for decades. “Often all of us, we get hung up on the minutiae, and being so serious about life. What Tom has done is remind us for a long time that we should enjoy what we do, as well.”

“He’s very good at telling stories and some of them are self-depreciating. He relates well to people, which is very important trait as a dean because basically if you’re in that job, you’re never really ‘off,’” says Mike Chippendale, a professor emeritus of entomology and former CAFNR associate dean who met Tom in the ’70s.

Recently Tom took some time to reflect not only on his accomplishments, leadership philosophies and colorful stories, but the relationships that made them possible — with Alice, fittingly, by his side.

Favorite memories

It does not take long to accumulate a list of stories about Tom Payne that leave smiles on the faces of those telling them in their wake.

Some of the first stories that come up are frequently tied to the Fisher Delta Research Center Field Day in the Bootheel in Portageville, Mo., and how he could both work the crowd and kiddingly tease state politicians and ag industry leaders who took to the podium.

Lowell Mohler, the former director of the Missouri Department of Agriculture and current chairman of the Missouri State Fair, tells about the time that Tom shot a pigeon during the annual Delta tradition of dove hunting. “We said it was the last carrier pigeon in Southeast Missouri and he’s the one who shot it,” says Lowell, who also recalls when he went turkey hunting with Tom for the first time and his guest shot a bearded hen instead of a Tom turkey.

Bobby Moser, former dean of the College of Food, Agricultural, and Environmental Sciences (CFAES) at The Ohio State University, tells of the time that Tom brought two piglets in diapers riding in a child’s pedal car to Bobby’s birthday celebration.

“He knew I had that background so he brought these pigs to the party that day,” says Bobby, who had worked in swine research before becoming an administrator. “That went over quite well.”

“I forgot about that,” Tom says with a chuckle. “I’ve done a few things over the years that I thought were funny at the time.”

Still other memories just fit into the general category of laughter and jovial atmosphere associated with the numerous parties Tom and Alice hosted at their Columbia house — some of which are tied to the large plastic slide that runs from the top deck of their house to the backyard below.

“Alice has never, ever, in our entire married life said ‘Let’s not do that.’ In fact, she’s encouraged it, so we’ve always had functions here at the house,” Tom says.

Alice’s name, and the role she has played in Tom’s career, comes up in the conversation regularly.

“When you do something like a dean’s position, your spouse has got to be supportive. It almost takes two to do this job and do it right,” Bobby says. “Alice has always been very supportive of Tom. The two, they did it together. It’s just like my wife (Pat) and I. We look at it as a partnership and we worked together. The same thing with Tom and Alice.”

John Gardner says that he and has wife, Julie, had never experienced the blending of work life and personal life before coming to MU. Even though they lived and raised their children on an agricultural experiment station in North Dakota, they kept a separation of work and home life in their heads to preserve family time.

“I had modeled this approach of work-life balance, where they are separate worlds and it’s like you’re on a teeter-totter going back and forth between those two worlds,” Gardner says of his pre-MU mindset. “Tom modeled a totally different approach that threw all of that out of the window, saying that you’re one person. Work-life balance is a figment of your imagination. You will be more comfortable and spend less energy if you are one person and you integrate those lives.”

Robin Wenneker, who will be stepping down as president of the CAFNR Foundation at the end of this month, remembers one particular board meeting at the beginning of her tenure as a trustee in 2009 (during the Recession) in which Tom replied to a question about looking at ways to cut possible costs with an impassioned response that lasted approximately 45 minutes. Among those topics touched on were how to not lose out on opportunities for CAFNR while still avoiding laying off faculty and staff or interfering with student-driven research.

“I just remember being blown away at all of the parts that he was pulling together to keep this going under a quickly changing situation. It was amazing. It told you all of the different things he was thinking about in the College,” Robin says. “He was calling on problem solving, critical thinking and entrepreneurial skills to get them through tough times.”

The story that Ian Maw, vice president for Food, Agriculture and Natural Resources at the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities (APLU), tells may be the shortest one of all.

“Tom’s a stalwart and always has been. He has been at the forefront in leadership of every major issue affecting our land-grand institutions and the constituencies we represent,” says Ian, who first met Tom during his 34-year tenure at Rutgers University. “And as all of our counterparts have dropped away, he and I are probably the last dregs of the administrative heads we grew up with — you might call us dinosaurs, if you will, in terms of longevity.

“He and I had a bet on who would toss it in first and who would outlast the other. When he announced his retirement, he sent me an e-mail. It had two words in it: ‘You won.’”

‘I met her the day she was born’

Tom Payne was born on Oct. 17, 1941, in Bakersfield, Calif. — just 10 days before Alice was born in the same maternity home delivered by the same doctor.

“We were in the nursery together because I was there for 14 days, so I met her the day she was born, but she doesn’t remember that,” Tom says of the girl he would later properly meet while a student at the University of California-Santa Barbara (UCSB).

Tom’s father, Jerry, was a jobber for Shell Oil Company, among other pursuits including serving as a policeman, selling insurance and repairing electric shavers. His mother, Opal, took care of the home, while raising Tom and Bob, his older brother by 10 years, and volunteered as a Gray Lady for the American Red Cross.

“My parents were wonderful,” Tom says. “They had to put up with a mischievous kid.”

Tom, like his dad, worked several jobs. As a pre-teen, he delivered papers and mowed lawns. While in high school he worked in his brother’s gas station, then in an upholstery shop, putting seat covers in cars and covering furniture. Later he drove a truck delivering fuel oil to farms for his dad. After he and Alice were married, he earned money for college working in the summers as a fireman for the Santa Fe Railroad and as an oiler helper for Southern Pacific. He also loaded boxes of grapes in the vineyards near Arvin, Calif.

After entertaining thoughts of several career pursuits (medicine and psychology to name a few), he eventually found himself drawn into the world of entomology, particularly the study of insect behavior. Tom found a mentor in Adrian Wenner, a professor at UCSB who was the first to discover that bees communicate through odors and sounds as well as the well-known waggle dances.

Tom completed his bachelor’s degree in zoology from UCSB in 1965. He and Alice walked across the stage together, after she completed her degree in history. Tom then entered the graduate program in entomology at the University of California-Riverside where he would earn his master’s (1967) and his doctorate (1969) while working for and publishing with H.H. Storey, an expert in insect behavior.

Tom took his first teaching position as an assistant professor in entomology and forest science at Texas A&M in 1969, in spite of never having studied forestry or forest insects up until that point. Texas A&M, though, hired him for his expertise in the emerging field of insect phermones and the use of electrophysiology in the study of insect olfaction (the sense of smell). He proved to be a quick learner of forest entomology on his way to being named the research coordinator of a large, USDA-sponsored, 13-state project devoted to researching the southern pine beetle in 1974.

He also started to make international connections with fellow insect behaviorists. He would co-found the Journal of Insect Behavior 12 years later, which he still co-edits with Tim Paine, a professor of entomology at California-Riverside.

“If you come through the field of entomology, it in itself is an interdisciplinary science, insects involve plants, humans, animals, ecosystems, biodiversity, and so with his interest in insect behavior he got to know a lot of scientists in and out of the country,” says Mike Chippendale.

Tom’s involvement with the southern pine beetle project led him to meet a research technician in the entomology department at the University of Arkansas named Marc Linit at an Entomological Society of America conference in New Orleans in 1975.

“It’s one of those stories that I think is good to tell people early in their careers,” says Marc, the senior associate dean for research and extension who recently was named interim Vice Chancellor and Dean for CAFNR, effective Jan.1. “You meet lots of people, but you never know at the time how that could turn into a long-term relationship. But every once in a while you meet somebody and it’s not exactly that you worked with each other for a long time, but somehow you just stay in touch and they just influence your life. And that’s that relationship.”

While at Texas A&M, Tom received important advice from Perry Adkisson, the then head of the entomology department who hired him and would later become the system chancellor in the late ’80s: “You are what others allow you to be. Your success is what others perceive you to be.”

In the fall of 1985, Alice first met James Hundle, who had been serving as a volunteer fire fighter in the precinct where Tom and Alice and their two young children, Jacob and Joanna, lived. James struck up a conversation with Alice at a meeting after taking notice that a thank you card the Paynes had sent to the fire department was made using a Macintosh (“Mac”) personal computer that had come out a year earlier.

Alice told James that Tom had indeed bought a Mac and was experimenting with it while recuperating from back surgery. James, who also had a Mac and was a fellow enthusiast, started discussing and collaborating with Tom and Alice using his Mac to help with the volunteer fire department newsletter.

Later, Tom asked James if he wanted to help him pack up his laboratory for an impending move to Virginia Tech and go with him to Blacksburg to get the equipment installed. The Paynes were heading east as Tom had accepted the position of professor and head of the entomology department there.

“I thought it was going to be a summer job,” says James, who has now worked for Tom for 29 years, about the summer of 1987.

James stayed on as a lab technician to assist with the southern pine beetle research and to help get Tom’s laboratory off the ground, before switching to an administrative assistant/technical support role and eventually following him to Ohio State and Missouri. Over the years, Tom has asked James to be oversee a variety of CAFNR events including Mizzou Central, MU’s presence at the Missouri State Fair, beginning in 2004; the operation of the Gathering Place Bed & Breakfast in 2008 and Sorenson Estate venue in 2015.

“It’s been like a boss, a father and a best friend kind of thing,” James says of his relationship with Tom.

Fostering a sense of family

While at Virginia Tech, Tom attempted to build a unifying sense of family spirit in the department to combat a low morale before his arrival. For several years, Tom and Alice would invite all faculty and students who had no family in the area to their home for Thanksgiving. As many as 30 people would crowd around the table.

“Everything is a family for Tom,” Alice says. “He’s really connected to the whole of it.”

“Life is more enriched when you have family,” Tom says. “I’ve always felt personable to people and I’ve always believed that the closer you are to people the better you will be as an individual and that the more you can accomplish and the more synergy that will happen because of emotions between you and other people. I guess another word for it is ‘team.’

“The best work that anybody does is when their heart and their soul are in that piece of work: artists, painters, musicians, vocalists… and I think the same thing is true for faculty in the classroom and the laboratory, extension people out in the field. People become committed. They become loyal and you don’t do it for them to become that way, but the end result is that you as an individual feel better, you feel welcomed, you feel more a part of it, you are more at peace, and as a result the whole organization benefits.”

When Tom arrived as the new director of the Ohio Agricultural Research & Development Center (OARDC) in Wooster, Ohio, in 1993, Bobby Moser had been in his role as CFAES dean for just two years. During the interview process, Bobby was looking for someone with concrete plans to join with him to build an ag school and extension system that was well suited for the 21st Century.

“What I liked about Tom is that he picked up that conversation right away. He had ideas on how we should approach it and what we should look like so I said, ‘Man this guy has ideas, he’s got passion,” Bobby recalls.

According to “Seeds of Change,” a book that outlines the history of the OARDC, Tom “brought a relaxed style to the center — one that he called ‘personal, proactive, and somewhere between democratic and autocratic.’” In an effort that would mirror what he would do in Missouri, Tom worked to expand the presence of the OARDC across Ohio through its branch stations.

Before he left for Mizzou in 1998, Bobby and others had a street named in Tom’s honor on the OARDC campus after he helped erase an approximate $9.5 million-deficit CAFES faced by reallocating funds and increasing income through entrepreneurial means and strengthened support from state legislators and ag industry leaders.

“He brought some creative ideas and some bold decisions,” Bobby says. “It wasn’t always popular with everybody but it was the right thing to do and he wasn’t afraid to do it.”

Faced with a much smaller budget deficit upon his arrival at MU, Tom applied the same approach to guide CAFNR to the black — and keep it there since 2001.

“Tom is very good at budget analysis and not spending money he doesn’t have,” Mike Chippendale says. “I’ve been to a lot of meetings where the first question he had was ‘How are we going to pay for this?’”

Creating a ‘Fresh Start’

It was a moment that Marc Linit will never forget. Following the retirement of Roger Mitchell as dean, Marc sat in his then office in Room 1-64 of the Agriculture Building. After having just filled out a form to nominate Tom as a candidate, he paused before sending the process into motion with a click of his mouse.

“I kind of hesitated for a second about hitting ‘send,’ but I thought ‘This would be interesting if he came here.’ Then I thought ‘OK, what the heck,” says Marc, who received help in recruiting Tom to MU from Mike Chippendale.

Although Bobby did not want Tom to leave Ohio, he was able to tell him first-hand about the benefits of working and living in Columbia, having worked at MU as the chair of the Division of Animal Sciences in the early ’80s.

Tom began his time at MU with a campaign known as “Fresh Start,” a strategic planning campaign that contained aspects of what had made him successful at Ohio State. It three main objectives: “discover, enlighten and bring smiles.”

He then proceeded to meet people who represented all facets of CAFNR and the state agricultural industries — from faculty, staff, students, alumni to committee members, state legislators and commodity group leaders. At the root of these meetings were four questions: “What is the College doing right? What are we doing wrong? What should we stop doing? What should we start doing?”

“He was trying to get a sense of the opinion of the College out there in the broader community,” says Mike, who was serving at the time as the interim associate dean for research and the Agricultural Experiment Station. Mike, along with John Gardner (associate dean for extension) and Paul Vaughn (associate dean of academic programs), formed one of three members of what was known as the “dean team” after Tom’s arrival.

Lowell Mohler, who graduated from CAFNR in 1958 and has worked with members of the College’s administrators for decades in various forms of leadership roles for state agricultural organizations, says that Tom “is the best I’ve worked with” when it comes to being a CAFNR spokesman.

“I think he took CAFNR to a new level. There’s just so many things that Tom was able to do with his personality,” Lowell says. “He was just a great salesman. He could take any project and get people to support it.”

“He is the spokesperson for CAFNR and he will just stand on the top of whatever and yell at the top of his lungs if it’s something he really believes in,” Linda Holsinger says.

When Richard Fordyce was named the director of the Missouri Department of Agriculture in 2013, one of the first phone calls he received was from Tom.

“He’s been active and he’s been engaged in agriculture,” Richard says. “And I’ve really seen that since I’ve become the director because there’s a whole bunch of places that I’m at that he’s at. He understands the relationships between different organizations, different groups, different people and how you can maximize the efforts of Missouri agriculture by knowing them.”

“I think it’s fair to say he’s the most connected dean around the state,” says Brady Deaton, former chancellor of MU and professor and chair of the agricultural economics department who served as the provost when Tom was hired. Brady and Tom had been on the Virginia Tech faculty at the same time in the late ’80s.

“He’s worked with economic development of the state in ways that a lot of people don’t even know. He’s been a tremendous leader in the academic community with his fellow deans.”

The first large task

When it comes to thinking about the legacy he will leave behind, Tom is hesitant to provide a list of accomplishments. In terms of taking pride in something, though, his mind shifts to the construction of the Christopher S. Bond Life Sciences Center — a $65 million task he faced the minute he decided to accept the job. Tom served as the chair of the executive committee in charge of its construction, working closely with a team that included Mike Chippendale, who was the campus faculty project leader and later became the Bond Life Sciences Center’s first senior associate director. Up until that point, the most Tom had raised for a building was $2 million.

Tom worked with Missouri Sen. Kit Bond, the center’s namesake, who attained $30 million of appropriations funding from NASA’s life science budget — which lead to Tom and Mike going to Washington, D.C., to meet with NASA officials. He also knew former Missouri Gov. Mel Carnahan had made a matching commitment of $30 million from the state for the center. The agreement stalled when the governor died in a plane accident in October 2000.

As fortune would have it, Tom was on hand when then Missouri Gov. Bob Holden held a press event in 2001 for the announcement of $35 million in state bonds going to the completion of what would be later called the Mizzou Sports Arena.

“We were standing there behind the governor and a reporter asked the governor ‘now that we have the federal government match the Life Sciences Center, will the state funds be released?’ I will never forget that,” Tom says. “I did not plant that. And the governor, who was in support of the life sciences, said ‘Yes.’ That was a very big day.”

Tom would go on to work with CAFNR’s Office of Advancement to secure private gifts from individuals and organizations for the center including the naming of Monsanto Auditorium, the Lowell and Marian Miller Discovery Garden and McQuinn Atrium in heart of the Life Sciences Center, which was named after CAFNR alumnus Al McQuinn and his wife, Mary Agnes. The McQuinns also provided the funding for the five-story “Joy of Discovery” artwork, which is located in the middle of the atrium.

Over the years Al, who graduated from the College in 1954 and turned his Ag-Chem Equipment Company into a multimillion-dollar international enterprise, developed an appreciation for Tom’s comparable entrepreneurial spirit and his ability to take seed money for grants and turn it into matches from federal agencies and individual donors — or produce even better results.

“Because of our confidence in Dr. Payne’s investment acumen we have chosen to donate funds to CAFNR to be held for any basic use or investment opportunity Dr. Payne determines to be productive and contribute to the advancement of CAFNR or the university in total,” Al says.

“I gained a great confidence in Tom’s ability to determine a worthwhile investment of the university’s funds for special purposes. I don’t think there was a time ever when he didn’t at least double his money. I just thought that was pretty darn smart on his part. He was just very good at that and it impressed me significantly.

“I hold Tom Payne in the highest of regard for who he is and for what he does. I think of him and Alice as great friends and people it has been a great privilege for me to have known.”

Some of those investments that have helped add value to the lives and careers of CAFNR students, faculty and staff under his leadership at the College include the National Swine Resource and Research Center (2003), Tiger Garden (2004), South Farm Showcase (2006), MU Grape and Wine Institute (2007), The Gathering Place Bed and Breakfast (2008), Poehlmann Educational Center at Bradford Research Center (2009), Float Your Boat for the Food Bank (2011), the Hortense Greenley Agronomy Building at Greenley Research Center (2015) and the Sorenson Estate venue (2015).

Going forward

For decades, Tom’s life has kept up the same fast pace at which his mind operates — jumping to a revenue-generating idea or having a moment of inspiration for an acrylic painting down in his basement studio or typing up an e-mail at 3 a.m. He has been known to have an idea pop into his head in regards to his backyard, jump out of his car and work on the issue clad in a suit.

“I’ve learned a little bit not to get out there in a suit and tie, but I’ve ruined a lot of clothes just by the impulse to do it. It’s the old adage ‘don’t put off until tomorrow, what you can do today’… or right now! I know if something needs to be done, I can’t rest until I do it,” Tom says. “I don’t think I procrastinate very well, but the synonym to that is impatience.”

“Tom’s been organizing other people all of his life,” Alice says. “That’s the truth. Those are his skills and so what he’s talking about is just the way he has always been able to achieve these goals by getting people together and getting it done.”

“It’s actually a drive I have no control over,” Tom adds.

“I was about to say that. You can’t help yourself,” Alice says with a chuckle.

So how does someone with such a drive to get things done finally go into retirement mode?

“I think it’s going to take some time,” says Linda Holsinger, who is about to enjoy her own retirement from the College. “It is going to be difficult, but he’ll transition. He has hobbies. He likes to paint. It’s going to be tough, though.”

“I think he can really bring a lot to the table for an organization or a group of people in his retirement years,” Richard Fordyce says.

Tom says he does not know exactly what he will do, other than he wants to do what he can to help CAFNR and MU.

“I think taking advantage of the relationships that I have is important to do during a transition period in order to benefit CAFNR and MU,” Tom says. “I want to be there to help do what I can if asked. If somebody wants to use my input to help with something, I’m happy to be there.”

Marc Linit is confident Tom will have plenty of opportunities to continue to be a spokesman for CAFNR and MU.

“He’ll stay engaged. He has to stay engaged,” he says. “It’s part of his DNA and we’ll use him effectively.”

There’s also sure to be more trips to Denver for Tom and Alice to visit their two grandchildren (Jacob’s children), Caroline and Jack — as well as Austin, Texas, to visit Joanna.

One thing is for sure: The Paynes do not plan on doing a lot of big trips, compared to newly retired couples. Given how many work and personal trips they have taken across the world, “staying home more looks pretty good,” Tom says.

“Sleeping in past 5:30 or 6 in the morning looks pretty good, too.”