When the Missouri Legislature finally got off the dime in 1868 and got serious about establishing a college of agriculture with the federal Morrill Act money, there was no shortage of counties wanting the new school.

The establishment of an agriculture college was a big deal. Virtually all of the state’s economy was based on farming. An agricultural college would bring the smartest scientists, prestige and economic development to a community.

And the placement of the agriculture college was up for grabs. The Morrill Act specifically said it should not be located within an existing university – a rule that established, for example, Kansas State Agricultural College (now Kansas State) apart from the existing University of Kansas.

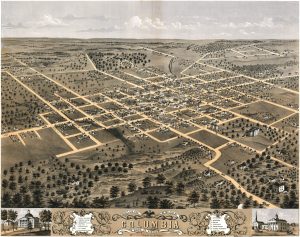

Missouri counties pledged significant amounts of land and bond money to bring home the new school, with Sedalia, Springfield and Independence being top contenders. Ultimately, Boone County and the University of Missouri got the college, with a good, but not best, offer. What they had was a better political plan which, incidentally, helped grow Lincoln University and establish what is now the Missouri University of Science and Technology in Rolla. Boone County’s plan also got around that pesky Morrill Act rule prohibiting the new agriculture school from aligning with MU.

The Morrill Act Gets Things Rolling

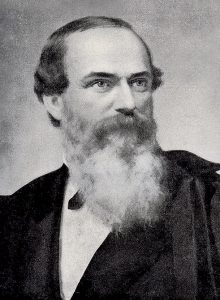

Justin Smith Morrill (1810-1898), a Vermont congressman, in 1857 introduced a bill to finance the establishment of colleges of agriculture through sale of federal lands. President James Buchanan vetoed that bill, saying it would create a “struggle among localities concerning the division of the gift.”

The bill was reintroduced, passed and signed by President Abraham Lincoln in 1862. By joint resolution in 1863, the Missouri Legislature accepted the act, but did nothing for the next six years to implement it, forcing Congress to extend the 1868 deadline. Congress sternly warned Missouri to form its agriculture college by May 1870 or lose the endowment.

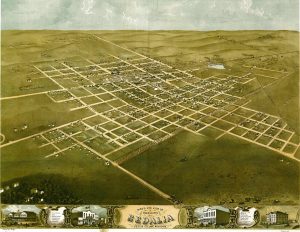

With that, a great competition arose in Missouri over where to locate the new college. Rocheport and Lexington told the Legislature they were the best because of their riverboat docks. Sedalia claimed the best soil and central railroad location. St. Louis said they were the natural choice as the only real civilization around. Fast-growing St. Joseph, perched on the edge of the frontier, expressed an interest, also.

The same civic leaders who brought the University of Missouri to Columbia in 1839 wanted the college, too, and pledged to offer bond money and land to locate it in Columbia.

The Morrill Act money was the biggest chunk of cash to hit the state made poor by the Civil War, according to the book University of the State of Missouri Record Facts Relating to the Creation, Location and Maintenance of the College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts and the School of Mines and Metallurgy. The expected endowment was more than $400,000 (about $7 million in today’s value).

Boone County Opens the Bidding

In December 1868, James S. Rollins (1812-1888), the Father of Mizzou, told the MU Board of Curators that almost 900 Boone County citizens had pledged a donation of $50,000 ($800,000 today) to purchase 300 acres of land for a college farm as an inducement to bring the college to Columbia. This was the same gambit that brought MU to Columbia almost 30 years before.

This time a bidding war erupted. In January 1869, Pettis County pledged $35,000 and 640 acres of farmland (now occupied by the Missouri State Fair campus) to locate the agriculture college in Sedalia. Greene County pledged $100,000 ($1.6 million today) and 640 acres to bring it to Springfield.

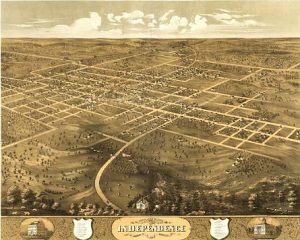

Jackson County topped them all with an offer of $150,000 in cash ($2.5 million today) and 420 acres of land south and west of Independence. The effort was headed by the Jackson County Agricultural and Mechanical Association.

The Missouri Statesman newspaper of April 1, 1869 reported that the idea of “putting the location of the agriculture college up to the highest bidder seems to agree with many in the Legislature.”

Jackson County was booming by outfitting wagon trains trekking to Santa Fe and California. There was little hope of Boone County, still recovering from the Civil War, competing with that economic colossus.

Rollins knew, however, that it would not be money but votes in the Legislature that would decide the match. Now a representative in the Missouri Assembly, he looked for political allies.

Rollins Builds a Coalition

It was well known that underneath southeastern Missouri was a treasure of lead, zinc and copper. Efforts to create a mining school there went nowhere, however. Missouri had been devastated by the Civil War. Bills to create a school couldn’t get a co-sponsor, much less a floor vote. There was no money.

Rollins met with southeastern Missouri legislators. His pitch was simple – in exchange for the region’s support of the college of agriculture coming to Columbia, Rollins would add language to his bill that would direct some of the Morrill funds to establish a school of mining somewhere in their area.

To comply with the Morrill Act designed to promote agriculture, the mining facility would initially be a subsidiary of the college of agriculture. The southeastern legislators grabbed it.

Rollins wasn’t done. He visited Cole County’s delegation who unsuccessfully tried to get funds to establish teacher training at the Lincoln Institute, a college formed in Jefferson City in 1866 to educate soldiers of the 62nd Infantry. They agreed to vote for Rollins’ bill, too, for some of the Morrill Act money.

To sweeten Columbia’s deal, Rollins got a further pledge from Boone County and Columbia to issue $80,000 and $10,000 in bonds, respectively, to bring their bid up to $90,000 and 640 acres of land. This bid was still under the one from Independence, but respectable.

As for that pesky Morrill Act proviso stating the new college of agriculture shouldn’t be part of an existing university, Rollins said there was nothing in the law that said the schools couldn’t be adjacent (thus resulting in the red campus of the liberal arts MU and the white limestone campus of the agriculture school). As the Board of Curators would operate both schools under Rollins’ bill, it would be a distinction without a difference.

Rollins Gets His Vote

Rollins’ timing was exceptional. His bill was just about the only thing viable on the Missouri Legislative docket in January 1870. Other cities were still squabbling or trying to come up with their own proposals.

With the Congressional use-it-or-lose-it deadline approaching, a vote Feb. 2, 1870 in the Missouri House approved Rollins’ bill – with the expected supporting votes by southeastern Missouri counties and Cole County. Opponents could only offer amendments, most of which were voted down, according to the House Journal of 1870.

The bill then went to the Senate on Feb. 9, 1870 and immediately came under criticism, according to the 1870 Senate Journal. Jackson County opposed it because of Boone County’s sympathy to the Confederacy. It also claimed its offer was 50 percent better.

Nonetheless, with the deadline weeks away and no better alternative available, Rollins’ bill passed the Senate. Governor Joseph McClurg signed it into law.

The establishment of the school of mines and Lincoln’s teaching program diluted the college of agriculture’s endowment from more than $400,000 to around $360,000. The mines school today is known as the Missouri University of Science and Technology. Lincoln University’s Teacher Education Program remains operational to this day.

What Might Have Been

Had Jackson County’s bid won, Missouri’s independent college of agriculture would have been one of the richest of the land-grant institutions. With the full $400,000 Morrill money and $150,000 from the county, the combined endowment would have been worth more than $10 million in today’s money.

That initial funding would have dwarfed MU’s original endowment of $160,000 ($2.6 million today). As Jackson County was undergoing a land boom, any sale of the 420 pledged acres would have added to the new school’s accounts. Such riches probably would have transformed Missouri’s college of agriculture, located near Kansas City, into a separate state land-grant university as occurred with Kansas State, Iowa State and Michigan State.